It seems simple enough– if one does something wrong or offensive, one apologises, and ideally the matter should be settled. However, as a celebrity, apologising is not simply a matter of “mea culpa,” thank you and goodbye. It becomes a PR tool because idols are made up of as much image as real person, and their dependance on public favour makes it crucially important that in the event someone does something wrong, at least the apologising (or not apologising) should be done right.

It seems simple enough– if one does something wrong or offensive, one apologises, and ideally the matter should be settled. However, as a celebrity, apologising is not simply a matter of “mea culpa,” thank you and goodbye. It becomes a PR tool because idols are made up of as much image as real person, and their dependance on public favour makes it crucially important that in the event someone does something wrong, at least the apologising (or not apologising) should be done right.

Recently Heechul apologised for being overly defensive over Sulli’s dating scandal when it was brought up last year, yet he received flak for bringing up an incident that most had forgotten. The thing is, he did not even bring up the incident himself, yet the netizens were quick to jump on his apology and pour scorn on it. Thus, it appears that making apologies is an art form in itself, in order to avoid igniting a new wave of criticism when people find fault with the apology.

There exists a wide spectrum of offences idols apologise for, ranging from the trivial–like Jay Park’s planking on ramen boxes–to the more serious, like G-Dragon’s marijuana scandal back in 2011. Apologies can come in the form of a tweet, press conference, video, or even an official statement released by the company the offender belongs to. How well-received an apology is, however, seems dependent on several factors, not limited to medium and content.

There exists a wide spectrum of offences idols apologise for, ranging from the trivial–like Jay Park’s planking on ramen boxes–to the more serious, like G-Dragon’s marijuana scandal back in 2011. Apologies can come in the form of a tweet, press conference, video, or even an official statement released by the company the offender belongs to. How well-received an apology is, however, seems dependent on several factors, not limited to medium and content.

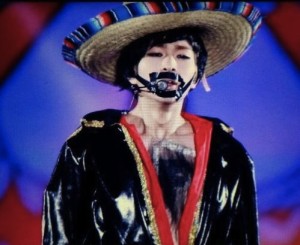

The first and most obvious is the severity of the incident in question that created the need to apologise in the first place. Of course, the apology is not always directly proportionate to the offense committed– it seems as though idols are forever apologising for rather run-of-the-mill, insignificant incidents, such as miss A‘s Jia’s riding on an airport cart and posting a video of it, while a lot of “bigger” incidents either fly under the radar or are settled with a half-assed apology. However, in a lot of cases where incidents truly offend– such as Minho and Onew’s appropriation of Mexican culture, black tape moustaches and all, or the various appearances of blackface in the media– a mere apology is frankly not the main issue there. Although it would help to receive acknowledgement that said behaviour has offended through an apology, perhaps what is more important is the need to spread awareness that such behaviour is even offensive in the first place, and that is a whole other can of worms which has been discussed before.

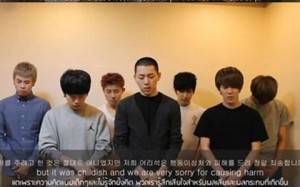

There is a tendency for incidents to be overblown even after apologies are made, because netizen culture lends itself very easily to mob psychology and mass hysteria. One needs to look no further than Block B’s interview in Thailand a couple of years ago that quickly escalated into an example of online witch-hunting, even after the group repeatedly apologised on official channels and leader Zico shaved his head in a gesture of contrition. Death threats were made, petitions for disbandment were created, and generally a mass outpouring of viciousness was directed towards the group.

The irony lies in that what most people found offensive, the group’s supposed tarnishing of Korea’s international image by making light of the floods in Thailand while interviewing there as representatives of their country, was due to a mistranslation that gained traction too fast for the truth to catch up on. Despite the sincerity in the group’s attempts to atone for their lapse in behaviour, it did little to soothe the grievances of the netizens. Eventually, though, Block B was able to stage a successful comeback with “Nilili Mambo.”

This is only a singular incident out of many that have occurred in past years. Careers have ended over lesser incidents, and careers have also bounced back after greater ones. Arguably, the resilience of an idol or group’s career in the face of a scandal depends on the status of the idol or group itself, as well as the strength of the company behind it, in order to have the resources to suppress negative press, garner support and make savvy PR decisions in what to officially release to the public. Because apologising basically means to admitting to having done something to apologise for and subsequently taking responsibility for it, it is up to the company whether to release an official statement or choose to make no comment.

In the case the company or idol in question does choose to go the route of public penance, however, sincerity and timing are essential. It does not really do any good to appear to be apologising for the sake of apologising (bonus points if a really detailed yet dubious backstory is included), or worse, to apologise for untrue statements made prior, most common in the revelation of idols dating. The public likes remorse and repentance, not continued denial. But above all, the public likes a good comeback– in fact, I’m inclined to believe that the post-scandal comeback will do more to adjust public expectations towards the idol or group and rehabilitate their images, for apologies and more apologies can only go so far.

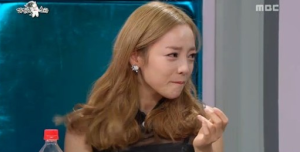

However, it appears that in incidents where more than one group is involved, the question of who apologises is usually dependent on the status of the group. For instance, during the infamous “Radio Star” incident last year, KARA’s Goo Hara shouldered the majority of the criticism for acting unprofessional by being provoked to tears while filming after the MCs made continuous references to her past dating experience, and for generally overreacting. On the other hand, a portion of people were calling for the MCs to apologise instead, and eventually both sides issued apologies, but the fact remains that KARA bore most of the pressure to apologise compared to the other parties involved in the incident. Call it a double standard, call it bias, but as guests on the show, KARA were expected to behave in a certain manner and react appropriately to a known “hard-hitting” show, and when they were unable to, they received the disapproval of the public accordingly.

However, it appears that in incidents where more than one group is involved, the question of who apologises is usually dependent on the status of the group. For instance, during the infamous “Radio Star” incident last year, KARA’s Goo Hara shouldered the majority of the criticism for acting unprofessional by being provoked to tears while filming after the MCs made continuous references to her past dating experience, and for generally overreacting. On the other hand, a portion of people were calling for the MCs to apologise instead, and eventually both sides issued apologies, but the fact remains that KARA bore most of the pressure to apologise compared to the other parties involved in the incident. Call it a double standard, call it bias, but as guests on the show, KARA were expected to behave in a certain manner and react appropriately to a known “hard-hitting” show, and when they were unable to, they received the disapproval of the public accordingly.

Outside of apologies, “Oppa/Unnie didn’t mean it!” is becoming an increasingly common catchphrase on the internet, whether used by fans to defend their bias or by people looking to discredit the whole business of blindly protecting one’s bias. It is undeniable that one will be more inclined to forgive a celebrity one likes than a celebrity one dislikes or is indifferent towards, and in a way, the strength of a fanbase can also determine whether the apology will be accepted or rejected. After all, when idols apologise, a lot of the repentance is directed towards the fans who supported them all along, and when a significant portion of the fanbase withdraws its support, it can be a blow to the group in terms of public image and group morale when it seems that even their own fans do not support them.

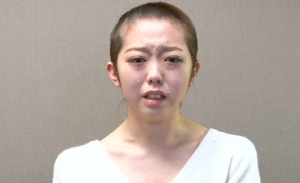

Interestingly, another incident that occurred within J-pop involving a celebrity apology was quick to spark off debate in the media about whether it was too extreme. AKB48 member Minami Minegishi filmed a video of herself profusely apologising to fans while sporting a shaved head after it was found out that she had a boyfriend, something expressly forbidden in her contract. Other than promptly morphing into the first big entertainment scandal of the year in Japan and taking up five trending-topic spaces on Twitter, Western media outlets such as The Atlantic posted articles condemning the “ridiculousness” of this strain of idol culture where there is “strict adherence to fantasy even at the expense of the performer’s humanity,” and that they have to go to such extreme means to repent for it when they break this fantasy. Then again, J-pop cannot be simply equated to K-pop in terms of idol culture, but overall the reaction towards Minegeshi’s public apology sparks an interesting debate towards the nature of celebrity repentance in this corner of the world.

Interestingly, another incident that occurred within J-pop involving a celebrity apology was quick to spark off debate in the media about whether it was too extreme. AKB48 member Minami Minegishi filmed a video of herself profusely apologising to fans while sporting a shaved head after it was found out that she had a boyfriend, something expressly forbidden in her contract. Other than promptly morphing into the first big entertainment scandal of the year in Japan and taking up five trending-topic spaces on Twitter, Western media outlets such as The Atlantic posted articles condemning the “ridiculousness” of this strain of idol culture where there is “strict adherence to fantasy even at the expense of the performer’s humanity,” and that they have to go to such extreme means to repent for it when they break this fantasy. Then again, J-pop cannot be simply equated to K-pop in terms of idol culture, but overall the reaction towards Minegeshi’s public apology sparks an interesting debate towards the nature of celebrity repentance in this corner of the world.

In all, apologising for one’s misdeeds is only a small portion of the intricate song and dance all public figures take part in order to maintain the public’s good opinion. While K-pop does love its “Sorry Sorry,” it results in there being a glut of unnecessary apologies for trivial incidents when more attention should be paid to long-term problems of sexism, racism, et cetera within K-pop that are far more likely to offend than Jay Park crushing boxes of ramen under his body weight.

(The Atlantic, Nate, EnKorea, The Korea Herald, Images via SBS, Jay Park’s Twitter, King Records, onewsama, MBC, Brand New Stardom)