The words “K-pop” and “idol” have gone hand in hand for as long as anyone can remember due to the K-pop industry’s reliance on an idol system which has established an assembly line process of auditioning and training in creating quality idols deemed suitable for debut. However, in recent years, this convention of idol production has realized a gradual change. With the rise in popularity of televised singing competitions, most notably Superstar K and K-pop Star, the industry has created a demand for new types of entertainers who are more artistically versed and musically involved in their releases. This new breed of entertainer combines the training and marketing of an idol with the musical talents of an artist, hence I coin them the “idol-artist.”

Before I continue, it’s important to define the characteristics and the problematic implications that are attributed to the term “idol.” After passing several rounds of auditioning, idols undergo several years of training under a management agency and are continuously monitored and micromanaged in the years following their debut. Idols are manufactured to be perfect, their image trimmed to the minutest detail, and their behavior appropriated to be acceptable by the public. They have little or no say in the artistry or production of their music. They are told what to perform and how to perform it. And if they have a problem with that, their only option is to either withdraw as idols and return to utter obscurity or to take their management agency to court.

Aside from being performers, idols first and foremost are celebrities. When recruiting for idols, entertainment agencies look for visual qualities more than anything else. Musical qualities are indeed important as well, but agencies believe they can harvest the musical potential (whether it’s there or not) of their young and budding recruits through years of dedicated training. The aftermath of the idol system results in the wasteland of idols groups which litter the current state of K-pop. Agencies try to make the most out of the investments they put into their many idol recruits by placing them into groups despite an idol’s dearth in an area of performance, which becomes especially noticeable when that lacking attribute is live performance ability. These “black hole idols” bring down the overall quality of a group’s performance, thereby creating today’s K-pop scene which is filled with idol groups who are mediocre live performers. Having lowered the bar for musical talent, and forcing K-pop fans to have to appreciate their favorite idol performances through a lowered standard, or through a “K-pop context,” this lack of talent in the realm of idols has led the K-pop world to demand more originality and musical ability from its entertainers — the call for more artists and less idols.

Aside from being performers, idols first and foremost are celebrities. When recruiting for idols, entertainment agencies look for visual qualities more than anything else. Musical qualities are indeed important as well, but agencies believe they can harvest the musical potential (whether it’s there or not) of their young and budding recruits through years of dedicated training. The aftermath of the idol system results in the wasteland of idols groups which litter the current state of K-pop. Agencies try to make the most out of the investments they put into their many idol recruits by placing them into groups despite an idol’s dearth in an area of performance, which becomes especially noticeable when that lacking attribute is live performance ability. These “black hole idols” bring down the overall quality of a group’s performance, thereby creating today’s K-pop scene which is filled with idol groups who are mediocre live performers. Having lowered the bar for musical talent, and forcing K-pop fans to have to appreciate their favorite idol performances through a lowered standard, or through a “K-pop context,” this lack of talent in the realm of idols has led the K-pop world to demand more originality and musical ability from its entertainers — the call for more artists and less idols.

If an idol is basically a manufactured performing puppet tailored towards mass public consumption, then what defines an “artist” and how are they different from idols? While idols and artists both release, promote, and perform music, the way in which artists do so is completely different. Firstly, artists have a say in the artistry, production, and performance of their own music. Artists are singers and songwriters whose musical ability is rarely put into question. Secondly, artists possess raw talent that is beyond that of the average person. Even if they have taken voice lessons, their vocal ability far exceeds the average person who has taken voice lessons. Lastly, artists are not manufactured; they are discovered. They are not trained for half a decade during their pre-teen years in preparation for their debut. Instead, they cultivate their performance and musical potential through self motivation and hard work while going about their regular lives, waiting for their big break, that one audition which brings them into the spotlight.

If an idol is basically a manufactured performing puppet tailored towards mass public consumption, then what defines an “artist” and how are they different from idols? While idols and artists both release, promote, and perform music, the way in which artists do so is completely different. Firstly, artists have a say in the artistry, production, and performance of their own music. Artists are singers and songwriters whose musical ability is rarely put into question. Secondly, artists possess raw talent that is beyond that of the average person. Even if they have taken voice lessons, their vocal ability far exceeds the average person who has taken voice lessons. Lastly, artists are not manufactured; they are discovered. They are not trained for half a decade during their pre-teen years in preparation for their debut. Instead, they cultivate their performance and musical potential through self motivation and hard work while going about their regular lives, waiting for their big break, that one audition which brings them into the spotlight.

Many of the finalists from each season of Superstar K and K-pop Star share one similarity. They possess undeniable musical and performance talent. Having transcended the idol system and gained publicity largely due to their talent, these performers are not only idols, they are idol-artists because of their ability to perform and craft their own music while being managed and marketed by even the biggest entertainment agencies in the industry. I label the industry’s push towards promoting half-idol and half-artist hybrids as the “idol-artist movement.”

The industry’s demand for idol-artists is being fulfilled on two separate fronts, one of which originated from from a sudden abundance of well-liked performers who gained celebrity by outlasting their counterparts through many exhausting rounds of elimination in the singing competition reality show and surprise hit, Superstar K. The first batches of idol-artists from the show received offers from upper-mid to low end entertainment agencies and have so far churned out notable careers. Seo In-guk, John Park, Huh Gak, and Jang Jae-in have debuted as solo artists and have generated some buzz with their promoted singles. Huh Gak was signed to A-Cube Entertainment, a subsidiary agency of the larger Cube Entertainment, which is arguably the fourth largest management agency in the industry. However, despite their modest success as solo artists, these performers have been designated into the minor niche of ballad singers whose primary hold on the industry is the demand for OSTs in the endless stream of dramas. Other than that, being cast on a variety show that requires legitimate vocal talent, such as Immortal Song, seems to be the marker of success for this early wave of idol-artists.

The industry’s demand for idol-artists is being fulfilled on two separate fronts, one of which originated from from a sudden abundance of well-liked performers who gained celebrity by outlasting their counterparts through many exhausting rounds of elimination in the singing competition reality show and surprise hit, Superstar K. The first batches of idol-artists from the show received offers from upper-mid to low end entertainment agencies and have so far churned out notable careers. Seo In-guk, John Park, Huh Gak, and Jang Jae-in have debuted as solo artists and have generated some buzz with their promoted singles. Huh Gak was signed to A-Cube Entertainment, a subsidiary agency of the larger Cube Entertainment, which is arguably the fourth largest management agency in the industry. However, despite their modest success as solo artists, these performers have been designated into the minor niche of ballad singers whose primary hold on the industry is the demand for OSTs in the endless stream of dramas. Other than that, being cast on a variety show that requires legitimate vocal talent, such as Immortal Song, seems to be the marker of success for this early wave of idol-artists.

Seeing that the top contestants from Super Star K’s first two seasons found only moderate success, the future fate of this type of idol-artist was put into doubt. Nevertheless, season three changed the game. The show’s inclusion of bands paved way for the likes of Busker Busker and Ulala Session. Sticking true to their indie roots, Busker Busker, wrote and produced all eleven tracks off their debut album, and the result was mind-blowing. Having every song on the album enjoy enormous time on the charts, with a handful reaching top spots, Busker Busker’s astonishing success for an indie band was epitomized when they won the top award on a music show, MNet’s M! Countdown, with their hit song “Cherry Blossom Ending.” Following suit, Ulala Session reportedly turned down the likes of SM Entertainment and YG Entertainment to start their own agency, Ulala Company. The initiative these two bands took towards controlling their own musical production and artistic direction truly makes them artists who have left the idol realm. While the success of Ulala Session has not matched that of Busker Busker, both artists have definitely found their niche in the industry and have proven that they will be players to watch out for in the near future.

Seeing that the top contestants from Super Star K’s first two seasons found only moderate success, the future fate of this type of idol-artist was put into doubt. Nevertheless, season three changed the game. The show’s inclusion of bands paved way for the likes of Busker Busker and Ulala Session. Sticking true to their indie roots, Busker Busker, wrote and produced all eleven tracks off their debut album, and the result was mind-blowing. Having every song on the album enjoy enormous time on the charts, with a handful reaching top spots, Busker Busker’s astonishing success for an indie band was epitomized when they won the top award on a music show, MNet’s M! Countdown, with their hit song “Cherry Blossom Ending.” Following suit, Ulala Session reportedly turned down the likes of SM Entertainment and YG Entertainment to start their own agency, Ulala Company. The initiative these two bands took towards controlling their own musical production and artistic direction truly makes them artists who have left the idol realm. While the success of Ulala Session has not matched that of Busker Busker, both artists have definitely found their niche in the industry and have proven that they will be players to watch out for in the near future.

Following in the success of Superstar K, the industry’s top three entertainment agencies (aka the big three) decided to capitalize on this new trend of the idol-artist by creating their own televised singing competition, K-pop Star. This time the stakes were a lot higher because, under the watchful gaze of two CEOs of the big three (and BoA), the top contestants were pretty much guaranteed to be signed by a major management agency. The question then was not IF these top contestants were going to become stars but WHEN they were going to become stars. So far we’ve already witnessed the debuts of two top contestants from the show — Baek Ah-yeon as a solo artist and Park Ji-min as part of the duo 15&, both under JYP Entertainment. YG Entertainment has already announced the consolidation and anticipated debut of the show’s top runner-ups in the group SuPearls, along with the upcoming solo debut of Lee Ha-yi. 15 of the show’s contestants have signed with established agencies, some of which are outside of the big three like Starship Entertainment and DSP Media. With the success of these reality show singing contestants, continuing seasons of Superstar K and K-pop Star, and the creation of new singing contest reality shows by other networks, this first type of idol-artist is evidently here to stay.

Following in the success of Superstar K, the industry’s top three entertainment agencies (aka the big three) decided to capitalize on this new trend of the idol-artist by creating their own televised singing competition, K-pop Star. This time the stakes were a lot higher because, under the watchful gaze of two CEOs of the big three (and BoA), the top contestants were pretty much guaranteed to be signed by a major management agency. The question then was not IF these top contestants were going to become stars but WHEN they were going to become stars. So far we’ve already witnessed the debuts of two top contestants from the show — Baek Ah-yeon as a solo artist and Park Ji-min as part of the duo 15&, both under JYP Entertainment. YG Entertainment has already announced the consolidation and anticipated debut of the show’s top runner-ups in the group SuPearls, along with the upcoming solo debut of Lee Ha-yi. 15 of the show’s contestants have signed with established agencies, some of which are outside of the big three like Starship Entertainment and DSP Media. With the success of these reality show singing contestants, continuing seasons of Superstar K and K-pop Star, and the creation of new singing contest reality shows by other networks, this first type of idol-artist is evidently here to stay.

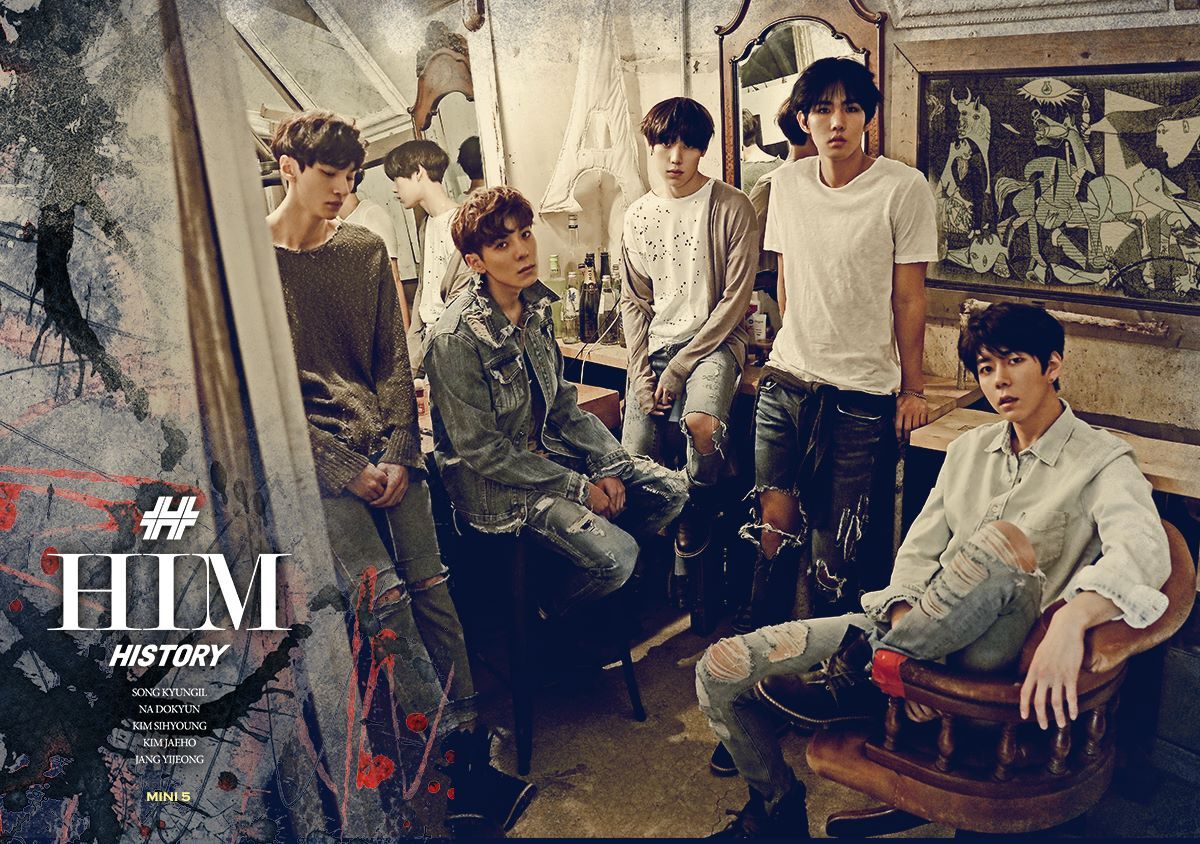

The other front responsible for supplying the industry with idol-artists is the entertainment agencies who recruit, train, and debut idols with the appeal of an artist. This marketing strategy began before the success of the original Superstar K contestants but has picked up speed with the achievements of early idol-artists. FNC Music has been the leaders in pioneering the concept of the “idol band,” which brings a flavorful twist to the idol formula by having idols display their vocal and instrumental abilities over their dancing and visual prowess. Although these performers may undergo many years of training before debut, their musical and live performance talent, along with the freedom they receive in the production of their own music, also qualifies them into the category of idol-artist.

This second type of idol-artist is particularly condensed under the management of FNC Music with idol bands FT Island and CNBlue. Like Busker Busker, CNBlue has their roots in indie, debuting in Japan and producing music in English and Japanese before entering the Korean market. Although marketed as idols, CNBlue actually controls a lot of their musical production as their lead vocalist, Jung Yong-hwa, is a singer-songwriter who has a heavy hand in composing the lyrics, music, and arrangement of the group’s songs. Similarly, FT Island’s lead vocalist, Lee Hong-ki, is not only noted for his influence on the band’s musical production, but also for his strong distinct voice. The success of these idol bands has led to other acts that have followed suit. LED Apple and FNC’s own AOA are derivations of the idol band that lean more towards the category of idols. They are marketed less so for their music and more so for their youthful looks. AOA is a mind-boggling mix between idol band and dance group in which certain members are designated for dancing, instruments, or even both. It’s as if their creative team couldn’t make up their minds on the artistic direction of the group and made a really unsavory compromise.

This second type of idol-artist is particularly condensed under the management of FNC Music with idol bands FT Island and CNBlue. Like Busker Busker, CNBlue has their roots in indie, debuting in Japan and producing music in English and Japanese before entering the Korean market. Although marketed as idols, CNBlue actually controls a lot of their musical production as their lead vocalist, Jung Yong-hwa, is a singer-songwriter who has a heavy hand in composing the lyrics, music, and arrangement of the group’s songs. Similarly, FT Island’s lead vocalist, Lee Hong-ki, is not only noted for his influence on the band’s musical production, but also for his strong distinct voice. The success of these idol bands has led to other acts that have followed suit. LED Apple and FNC’s own AOA are derivations of the idol band that lean more towards the category of idols. They are marketed less so for their music and more so for their youthful looks. AOA is a mind-boggling mix between idol band and dance group in which certain members are designated for dancing, instruments, or even both. It’s as if their creative team couldn’t make up their minds on the artistic direction of the group and made a really unsavory compromise.

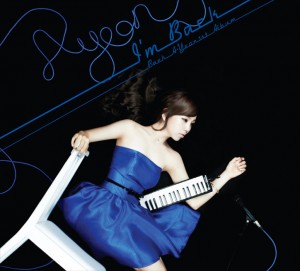

Aside from idol bands, there are two female soloists who have carved out a niche in the idol-artist movement through being marketed as singer-songwriters. Before IU became immensely popular, her vocal and musical ability was promoted very well in her acoustic covers of popular songs. Loen Entertainment has done a great job in crafting her image as not only the nation’s little sister, but as purely an artist who can do wonders with an acoustic guitar. Following in the footsteps of IU, FNC soloist, Juniel, has already demonstrated her amazing voice and guitar skills, which combine to create great music with a genuine acoustic flair. Both performers enjoy freedoms in writing and composing their own music. Both are truly artists and are being rightfully marketed as such.

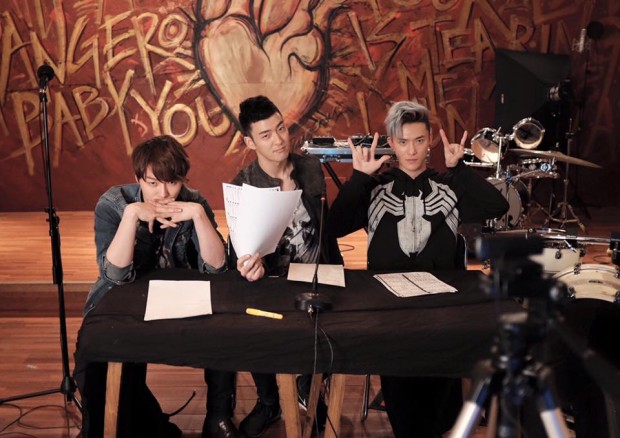

Then there is Lunafly. They’ve been compared to the likes of FT Island, CNBlue, LED Apple, and even SHINee. They’ve already released music in both English and Korean. They play acoustic guitars, keyboard, and even the djembe. They can harmonize. They are youthful. They are good looking. They are marketable. And they are amazing live performers. Check it out:

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LXLVXHirBns&w=560&h=315]Excuse me if I am at a loss for words when describing Lunafly. Nega Network has taken into account the idol-artist movement and further blends the lines between idol and artist in their marketing of Lunafly. First of all, they are being promoted largely as artists. Lunafly’s single “How Nice would it Be” was lyrically adapted by hit lyricist Kim Eana from the original English version, titled “Super Hero,” which was composed by the band members themselves. IU, Lunafly gives off a strong artist vibe in that they can create their own music and they can definitely perform live without the glaring aid of annoying back tracks. Furthermore, like the successful idol bands before them, they were recruited, trained, and are definitely being sold as idols with those topless teaser images.

Finally, Lunafly is completely different from any of the idol-artists previously mentioned because they incorporate one final element that is bold and fresh, the YouTube artist aesthetic. Their MVs for “Super Hero” and “How Nice would it Be” cannot get any simpler in that it consists of the three members performing with their instruments in front of three mics. Their YouTube channel nicely compliments these two MVs with videos of their practice clips and live performance, which pretty much sound and feel the same as their MVs. They are attempting to bridge the gap between the glamour of the MV and the spark of the live performance – the respective domains of the idol and the artist. Furthermore, their low-key videos resemble the numerous YouTube artists out there who are trying to get noticed and become the next Justin Bieber, or Karmin, by posting their covers and original performances on YouTube. By sharing the aesthetic of these (metaphorically speaking) starving YouTube artists, Lunafly creates the illusion of being the everyman artist while still enjoying the exposure and glitz of an idol.

Finally, Lunafly is completely different from any of the idol-artists previously mentioned because they incorporate one final element that is bold and fresh, the YouTube artist aesthetic. Their MVs for “Super Hero” and “How Nice would it Be” cannot get any simpler in that it consists of the three members performing with their instruments in front of three mics. Their YouTube channel nicely compliments these two MVs with videos of their practice clips and live performance, which pretty much sound and feel the same as their MVs. They are attempting to bridge the gap between the glamour of the MV and the spark of the live performance – the respective domains of the idol and the artist. Furthermore, their low-key videos resemble the numerous YouTube artists out there who are trying to get noticed and become the next Justin Bieber, or Karmin, by posting their covers and original performances on YouTube. By sharing the aesthetic of these (metaphorically speaking) starving YouTube artists, Lunafly creates the illusion of being the everyman artist while still enjoying the exposure and glitz of an idol.

In summary, the idol-artist movement has developed on two fronts: the popularity of televised singing competition contestants, and the public’s demand for performers who can create their own music and hold stunning live performances. From the likes of Busker Busker to CNBlue to Juniel to Lunafly, what are your thoughts about performers who are at the forefront of the idol-artist movement? Are they idols, artists, or hybrids of both? Which direction do you think the industry is heading towards: idols or artists? Leave your comments below!

(Nate 1, 2, officialLUNAFLY, Nega Network, SBS, Jellyfish Entertainment, A Cube Entertainment, CJ E&M, JYP Entertainment, FNC Music, Loen Entertainment)