As K-pop has spread to other parts of the world, both South Asians and the South Asian diaspora can be counted among the legions of its fans.

We have covered Hallyu’s appeal to South Asians in the past, and we return to the conversation some years later to see how things have changed and perhaps remained the same. Joining Seoulbeats writers Aastha, Divya, Gaya and Zea is Anthea Isaac, from Destination Kpop, The Kraze and Let’s K-pop India.

Gaya: VAV is the latest K-pop act to perform solo in India, with KARD soon to follow. What could this mean for India and South Asia as a market for K-pop?

Aastha: Although K-pop has had a small but dedicated fanbase in India (and South Asia) for some time now, it’s only recently that K-pop acts like VAV and In2it have considered India as a viable option for fan-meets and concerts. Economically, this makes sense: the Chinese market has been out due to political tensions, and the large untapped Indian market could prove lucrative. Though only a small proportion of the population might be K-pop fans, the country (and region) is so large that this small number could fill at least a small venue. It makes the genre more accessible and mainstream to South Asian fans.

More than that, though, I hope K-pop acts touring South Asian countries allow for more intercultural exchanges. After K-pop groups started touring the Americas and Europe, there has been a heavier (and positive) influence of various genres and cultures in K-pop. Latin music, for example, has played increasingly influenced more recent songs: Super Junior’s “Lo Siento”, BTS’ “Airplane Pt. 2”, and Block B’s “Shall We Dance”. Eric Nam’s “Honesty” MV is another great example of celebrating the culture without appropriating it.

In the same way, it wouldn’t be unrealistic to hope that with actual interactions with South Asian culture, the mockery would reduce. From Norazo’s “Curry” almost a decade ago to Lee Hyori’s “White Snake” and Black Pink’s “Kill This Love” promotions, there have been too many instances where South Asian cultures were used for profit without proper research and/or respect.

Considering the growing influence of K-pop, it would be ideal to see more groups undertake South Asian markets to reach wider markets and larger audience bases; simultaneously, we could finally stop having consistent bouts of disappointment from K-pop idols misrepresenting and not appreciating South Asian cultures.

Gaya: K-pop’s spread in India is similar to Australia’s: start with lower-tier male groups, which hopefully leads to more K-pop acts touring. India has more advantages: it’s geographically close, there’s a large audience, and acts can safely rely on the North-east (the heartland of India’s K-pop fandom) while venturing into other regions. Both countries also have big-name local media companies (SBS Australia and Rolling Stone India, led by Riddhi Chakraborty), to help with publicity and marketing.

Another parallel is the focus on just these two countries in the region, to the detriment of fans nearby. Even within each country, it is difficult for all fans to get to the few cities picked out; but spare a thought for fans in Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and beyond who can’t easily travel to India.

It would be exciting if more South Asian influences were seen in K-pop, like in Orange Caramel‘s “Catallena” and f(x)‘s “Milk.” There’s already one SB Mixtape‘s worth of ‘Desi K-pop’, and I would love to make more. As Aastha said, it could lead to more humanisation, but any open acknowledgement of South Asian influences seems to lead to circuses like Oh My Girl‘s “Windy Day” promotions. Since the music is divorced from the people, it is easier to be cavalier about it; I hope when artists meet South Asian fans, they will endeavour to respect our humanity.

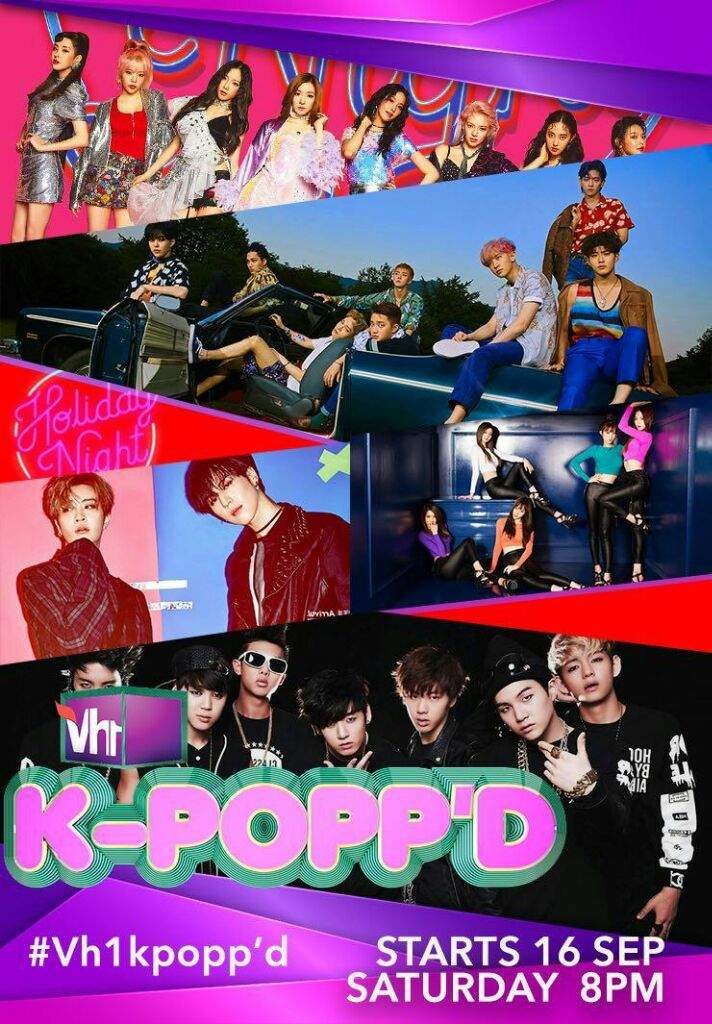

Divya: An impetus to K-pop has been given by the media in India through frequent reportage in newspapers and through television shows like VH1’s K-popped. It seems that K-pop has popularised itself in India, since it’s an amalgamation of two important ingredients of Bollywood music: catchy tunes and killer dance moves. Commercially, K-pop and Bollywood music may be marketed differently, but culturally they use similar tropes to rope in fans.

Despite these cultural transactions, India hasn’t been a destination for official tours until recently. Probably the closest outreach — at least geographically — initiated by a big-name agency was the SM Town concert in Dubai in 2018. Although it would be a while before bigger K-pop acts tour in India, the enigma that K-pop has created for itself in the urban youth will no longer keep India an invisible market for the industry.

Zea: K-pop spreading to India makes sense; not only is India a huge market but Indian cinema also heavily features music and dancing.

However, neither India nor Korea knows much about each other’s culture. I still remember when Exciting India aired; they surveyed the audience in the episode about what comes to mind when they think of India and everyone said “curry” — but South Asians have over a hundred variations of curry!? I also distinctly remember being displeased with Strong Woman Do Bong-soon‘s representation of the “monk from India.”

Also, shamefully, there exists a lot of anti-East-Asian sentiment among South Asian people. They often deem all East Asians the same, mock East Asian languages, and mock South Korean male idols who might not conform to hegemonic masculinity. Though I hope more idols visiting India allows both these cultures to interact and learn from each other, I am afraid that my hopes might be too high.

I agree that groups only seem to be focusing on India, and other desi fans are missing out. A small part of me wonders though, whether Koreans know of other South Asian countries or whether they think that all aspects of desi culture (“curry,” “Indian” dancing and clothing) come from India only. Do Koreans know that India is a huge country with different languages, dialects within those languages, religions, and religious practices, or do they think that all Indians practice Hinduism and speak Hindi? Even some of my North American peers are surprised to learn that’s not the case.

India and South Asia could be big markets for K-pop, but only if entertainment companies perform extensive market research and provide cultural training to their idols.

Anthea: Like everyone, I agree that India has a huge audience but is considered the least for K-pop events. A U.S.-based K-pop writer I know mentioned how America itself faced such a situation. A few years before, it was more of a dream to see acts perform concerts there; they also had to strive hard to get attention from idols. India is just going through the same phase. Within a year or two we can expect bigger acts like BTS, Exo and Got7 to visit.

To see such miracles, it is important to support smaller acts who decide to take a risk in the Indian market. It is obvious that people only recognise In2it and VAV, but acts like Mont and Lucente have also made their ways to Indian shores. It’s not that India or other South Asian countries are disregarded on purpose or carelessly; the companies are waiting for the right moment. We just have to wait a little while for history to repeat itself as it did with the U.S. and England.

The hesitation among Indians to attend K-pop events may be common, as civilians don’t believe much in spending on entertainment. Whether movies or music, people prefer to spend less or access it for free. This stereotype is gradually changing, though, and will possibly result in a positive outcome.

Another point to keep in mind is that Indian K-pop fans are mostly from the upcoming generation who are too young to step out for events without parents accompanying them. The present generation (including myself and my friends) are unable to attend events and concerts as we are students. We don’t have the income to spend or travel for our love of K-pop. Yet, the fans are equally determined and passionate about their idols so once they gain a stand for themselves, they will be mentally and monetarily be ready to meet their favourites.

Gaya: That is actually a great point regarding K-pop fan ages in India, Anthea! I’m looking forward to seeing what you guys do in the future.

I would love to see South Asian dance elements fuse into K-pop. Not classical dance forms like Bharathanatyam — they get butchered enough in local film and TV — but often I dream of a Prabhu Deva collab. Or get any of the other Indian choreographer working today: companies throw money at big-name Western choreographers who underdeliver; maybe it’s best to keep it in the continent, and if any of it has a Dravidian flavour, all the better. At the very least, people can learn what to do when they play “Tunak Tunak Tun” for the millionth time.

I felt apprehensive watching this Black Pink concert VCR of French fans dancing the way they did to “Tunak Tunak Tun.” It’s a fun song, but you see people acting too extra and you have to wonder how much of that is racism and ignorance. Sure, “Tunak Tunak Tun”‘s meme status is bigger than just K-pop, but remember “Gangnam Style”? Remember all the racist crap accompanying it? You don’t really know how much is genuine appreciation and how much is racist mockery.

I’m sure we’ve all experienced unsavoury moments as K-pop fans because of our South Asian identity: how do you deal with that, and what more needs to be done by idols and fans to eliminate this issue?

Aastha: A Prabhu Deva collab! I would definitely pay to see that. If I ever see something like a Farah Khan/K-pop collaboration, I’d probably lose my mind over how absurd (but cool) the whole situation would be.

Most of us seem to think there is a need for a willingness to learn about South Asian cultures, be it through dances and musical styles or cultural awareness, and it holds true. A common defense of actions like mocking Bharathanatyam moves is that it comes from a place of curiosity. My experiences as a South Asian, though, have made me wary to such arguments; I don’t know if it’s some sort of a sixth sense, but there’s a very obvious difference in genuine curiosity and offensive parodies.

It’s disheartening to see South Asian cultures butchered and ridiculed in K-pop, especially when you’re invested in the genre. Personally, it has been a journey from immature ignorance, to quiet acceptance, to barely concealed disappointment (and the occasional bout of anger).

Something I now appreciate from the rise of social media is the elevated connectivity between fans and companies. Previously, protests against cultural appropriation went unheard, solely because there were few ways for international — not just South Asian — fans to speak up about issues. With newer groups, though, at least fans have a way to collectively point out problematic behaviours and/or outfits. Anger and disappointment seem useless if they can’t be followed up with actions, but mediums like Twitter and even e-mail allow a more diverse fanbase to reach out to artists, or their management, when there’s misrepresentation occurring.

Still, more can be done by fans, idols, and their management. If an idol errs or offends a specific demographic of their fanbase (South Asian, in this case), then non-South Asian fans should give way to these fans to be heard. Coddling their idols or blaming management for their personal mistakes only goes to stop their growth as an individual. Most idols are imperfect adults, and it’s human to make mistakes; instead of sheltering them, fans need to support other fans when it comes to raising important points and arguments, even if it may “hurt” their idol.

At the same time, idols and companies have a responsibility to research on cultures they may choose to borrow from. I’m aware this all sounds idealistic and borderline unrealistic, but I do think that the slow (but necessary) process of widening your world-view and learning about other cultures and experiences is essential in not just reaching out to a wider fanbase, but also in being a true idol: someone whom others can look up to.

Gaya: Like everyone else, South Asian fans definitely deserve to be heard on issues affecting them.

With that also comes the issue what how things affect people within the South Asian community. We’ve already touched on how non-Indian fans have a different experience from Indian fans, but there are also differences between North Indian, North-east Indian and South Indian fans, native South Asian fans and fans among the diaspora, and bindis. These are much bigger issues, but K-pop is one place where we see them being played out. It’s a further complication to discussing cultural appropriation and racism in K-pop, but it is necessary to have those difficult conversations, even when it feels inconvenient.

I wonder how these conversations will continue to evolve, especially with two actual Indian K-pop stars now in the mix. When I see my new bias list queen Priyanka, I think of the beauty standards in South Asia that prevent me from seeing my own melanin reflected in my own culture, be it by whitewashing dark-skinned people or by excluding them altogether. Then I think of the stereotypical visualisation of what an “Indian” looks like and how that may be affecting Priyanka and the rest of us. And then you have Sid deleting his old Instagram post containing the N-word with no apology: hopefully, it provides an opportunity for more people to understand how prevalent anti-blackness is in Asian communities and what we need to do to eradicate it, among other issues.

Essentially, K-pop can help others learn about South Asian cultures and people — but it can also be an avenue for South Asians to learn more about ourselves and others.

(Hindustan Times, Next Shark, YouTube[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9]. Images via: Zenith Media Contents, DSP/Pink Box Events, VH1)