When you think of a girl crush, which K-pop idol comes to mind?

Chances are, you’ll think of more than one artist. It’s not surprising: many girl groups have dipped their toes into the girl crush concept, or developed it as their niche image. This seems like a given today, but just 12 years ago, the girl group scene looked very different. Back then, the chances of finding an idol with an image embodying female empowerment were like the odds of getting a fansign ticket by buying just one album: near impossible. So how did we get to where the scene is today?

This International Women’s Day, Pat and Qing review how the girl crush developed over the past decade, exploring questions of what it means to be an empowered woman in the context of K-pop releases. Does being a girl crush always imply female empowerment? And are idols who tap on traditional concepts of femininity necessarily forgoing agency?

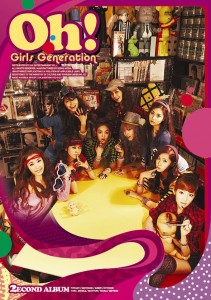

Qing: Before jumping in, let’s back up a little to set the scene. At the turn of the decade, female idol concepts fell into two categories corresponding to the Madonna-Whore dichotomy, which perceives women as either pure and chaste, or seductive. Idols were innocent and cute (epitomised by the all-white outfits and saccharine vocals of SNSD’s “Kissing You” and Kara’s “Honey”), or mature and sexy (Jewelry, Son Dambi, and the Wonder Girls). Whichever category they fell under, female idols were styled according to a heterosexual male audience’s fantasies and desires.

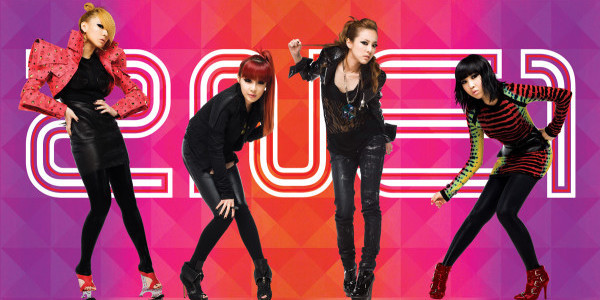

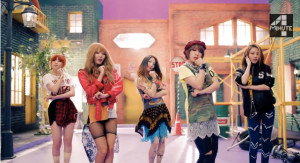

2009 was a watershed moment: it saw the debuts of girl groups who redefined the images of female idols entirely, pushing them beyond the familiar, polarised concepts of femininity. There was 2NE1, who pioneered the girl crush concept; 4Minute and f(x), who introduced middle ground to the innocent-sexy dichotomy with their fun, androgynous styling; and After School, who popularised the sultry take on the sexy concept, first introduced by senior labelmate Dambi.

Judging from the intense popularity of all of these groups, the K-pop audience were ready for different representations of women in the scene. However, the class of 2009 weren’t actually the first to push the envelope in this respect; Kara’s “Break It” (2007) was an early attempt at the girl crush, but it wasn’t well-received. What do you think contributed to the contrasting success of the 2009 debuts?

Pat: In the early to mid-2000s, Hallyu Wave mostly focused on Japan. Japan, after all, has a larger market than South Korea. it’s understandable that K-pop would cater to the Japanese audience in terms of image and sound. But from 2009 onwards, there was a steady uptick in acts expanding to the West, with little success.

This expansion of the Hallyu Wave laid the foundation for the success of later groups not just internationally but also domestically. Hip-hop has always been present, but 2009 marks the upward shift in the influence. During this time, trainees from Western backgrounds began to debut. Examples include Bekah, Park Bom, Amber, and Krystal from America, CL who spent her childhood in Paris and Tokyo, and Dara in the Philippines. They brought with them more liberal ideas in terms of femininity and gender roles, which show in their respective groups.

I think this influx of Western-raised idols debuting in the same year, at that moment when K-pop broke out internationally, is crucial to the understanding of empowerment in K-pop.

Qing: An artist’s profile can sometimes direct the company’s choice of concept for them. 2NE1’s diverse background is perhaps one reason why YG chose to style them in a radically different way from any girl group at the time.

2NE1’s first image in their futuristic debut MV, “Fire”, defies attempts at immediate judgment. Visor glasses and silhouettes hide their faces and bodies, allowing CL’s bold declaration, “we about to set the rules on fire baby”, to define them before their appearances do. They boldly appropriated hyper-masculine imagery usually reserved for male idols, like motorcycles, and the song’s theme of freedom was broke away from familiar themes of romantic love.

“Fire” had its problems, such as the designation of Park Bom as the “sex bomb” of the group in her Playboy bunny outfit, and the heavy appropriation of South Asian culture in Dara’s solo set. But 2NE1 undeniably revolutionised the image of female idols, paving a new, alternate path to the innocent-sexy dichotomy that other girl groups would come to traverse.

Pat: Another group debuting in 2009 with more subtle influence is f(x). They began with the company’s choice of concept to be experimental, to go beyond the K-pop market’s current trend. Like Shinee, it was more of a mission/vision statement.

Their discography highlights f(x) as not being bound by the same girl group definitions. They often played with that experimental sound, often emphasizing the worth of an individual person, especially from Pink Tape onwards. “Pretty Girl” critiques the societal mindset behind beauty standards and depending on a man, “All Night” and “Rude Love” center around a positive outlook on a mature relationship, and more.

In terms of styling, their personalities were often highlighted to portray them as being individuals rather than part of a single whole unit. Amber debuted with an androgynous look, keeping it even when they donned school girl uniforms for “Rum Pum Pum Pum.” Even when the group wore the uniforms, they did not play into the innocent or cute concept as predecessors have. They were whatever they wanted to be: androgynous, feminine, cute, hipster-y, all of the above.

2NE1 and f(x) were very different, but equally important to the realization that a girl group didn’t have to be cute or mature. f(x) were f(x), 2NE1 were 2NE1.

Qing: While these pioneering groups used their styling to shatter assumptions about the way female idols should look, it’s also important to consider the substance that supports their style. Their lyrics constructed the female persona as an active subject with agency (thoughts and actions taken by people that express their individual power), as opposed to an object that exists solely in relation to a man.

There’s the way 2NE1 expose an ex’s hypocrisy and infidelity, even as they admit their emotional vulnerability and lingering feelings, in “I Don’t Care”. Miss A’s “Bad Girl, Good Girl” calls out the patriarchal tendency to prematurely judge and label women based on their appearances. Even in exploring the typical theme of attraction, 4Minute’s “What’s Your Name” takes on a feminist slant with the persona bolding approaching a man she’s interested in, rather than playing coy or passively waiting for him to make the first move.

Entertainment companies certainly had a commercial agenda for pushing such concepts—the K-pop fanbase is predominantly female, and the girl crush taps on this demographic. The concept didn’t always work: sometimes, the idea of strong women was appropriated to present messages that were blatantly demeaning towards women.

Yet it’s clear that these girl groups opened doors for different forms of female representation, adding diversity to the restrictive Madonna-Whore perspective on women. Although most of these early third-generation girl groups have disbanded, a quick sweep of the current K-pop landscape shows that their legacy lives on.

Pat: Their influence is definitely felt. Itzy is a great example. While they may not be playing with masculine imagery as 2NE1 did in “I Am the Best”’, their lyrics carry on the legacy, but with a poppish take ala f(x).

Don’t measure me by your standards alone

I love being myself, I’m nobody else

…

Little time to care about what others think

I’m busy doing what I want to do

Another group is CLC. Their recent releases have a trend of questioning beauty standards. This is seen in “Me,” where they combine “the innocence of glamour/the purity in arrogance”, in “Devil” which tackles so-called bitchy behavior and asserting their right to have boundaries, and in “No,” where they proudly say they don’t need the typical markers of beauty:

Bring me something else, something most suited for me

Forget ways to look more “beautiful”

Screw how you feel, so “I” can look more like “me”

…

I don’t change myself for you

In all these songs, there is an emphasis that women can assert their agency and identity no matter their appearance.

Note: The next three paragraphs reference scenes that may recall sexual assault.

Qing: At the same time, there are groups that simply appropriate the girl crush concept to cash in on its success. Mamamoo debuted with a retro concept that emphasised their magnetism as performers without restricting them to archetypal images of female idols. But disturbing hints of sexual assault crept into their “Um Oh Ah Yeh” MV, with Hwasa (dressed as a lecherous man) pawing and pinning down Solar as she struggles against her, and Solar perving on Moonbyul.

Then came “Decalcomanie”, which severely normalised sexual violence by portraying them as acts of passion, as I discussed in my review. Violence is often romanticised in K-pop, but it’s more insidious considering Mamamoo’s image as strong women: it suggests that it’s normal for women of all types to accept, even covet, dating violence.

Mamamoo have made a lot of comebacks since, including the recent “Hip” MV that presents them as confident women in control of their lives. But because the troubling implications of their previous MVs were never adequately redressed, the shadow of those portrayals continue to loom large, reducing the credibility of their “girl crush” image.

Pat: On the surface, as YG Entertainment’s 2NE1 2.0, Black Pink seems to be the new-gen girl crush. But upon further inspection, the group fails to meet the standards of a girl crush as an empowered woman with agency.

Yang Hyun-suk was vocal about Black Pink having 2NE1’s sound, but with the appeal of SNSD. This isn’t a red flag, as we’ve talked about groups being a product of companies. But we’ve also seen how groups represented a new wave of female empowerment in K-pop through their lyrics. This is where Black Pink fails.

“Whistle,” with lyrics such as “Stop hesitating, come over to me” and “No need for many words, just take me to your side,” still places the first move on the male love interest. “Stay” pleads for an unhealthy relationship to continue. “Ddu-du Ddu-du” is CLC’s “Devil” but without the commentary on the bitchy persona, while revolving around physical appeal.

What about “Kill This Love,” one might ask. It’s a step in the right direction, with the lyrical content revolving around the decision to break up. But beyond the militaristic instrumentals, it lacks any semblance of depth due to the nonsensical lyrics. This depth is possible, as Sistar’s “I Like That” shows. Then there is “Playing with Fire.”

My mom told me every day

To always be careful of guys

Because love is like playing with fire

I’ll get hurt

My mom might be right

Because when I see you, my heart gets hot

Rather than fear

My attraction to you is bigger

Here we see the appropriation of the girl crush concept at its core: it’s stylistically packaged to be feminist, yet its substance takes away agency. The content is still similar to what we get from innocent concepts that tap into the virgin image, which sometimes plays into the Lolita complex.

The innocent concept is often disturbingly tied to female idols’ looks and young age. It’s underpinned by the patriarchal thinking that innocence means they must be protected: virginity is a prize, and innocent girls must be sexually preserved. This concept usually results in colorful doll-like dresses as seen in Kara’s “Honey.” It is seen in the reiteration of aegyo-filled “oppas” in SNSD’s “Oh.” School girl costumes, when combined with male gaze-y shots as someone with “natural makeup” is in a classroom setting, is a form of infantilization.

Qing: It’s important to note, however, that girl groups with traditionally feminine concepts aren’t always disempowered by such styling. This is where ideas from third-wave feminism come in. While second-wave feminism rejected typical images of femininity, believing them to be a product of patriarchal forces that restricted women, third-wave feminism reclaimed “girliness”, asserting that it is no less valuable than masculinity or androgyny.

What differentiates an objectifying use of the innocent/ sexy concepts from an empowering representation is whether the idols and the persona of their lyrics retain agency. Despite tapping into the pure schoolgirl look, GFriend’s debut trilogy is elevated by choreography that showcases their skill as performers, rather than pigeonholing them with simplistic, aegyo-filled gestures (think I.O.I’s “Very Very Very”), and lyrics that place them in control. “Glass Bead” conveys a message of strength (“I may seem like a clear glass bead / But I won’t break that easily”) and encouragement. “Me Gustas Tu” puts a similar spin on familiar themes of pure love, with the persona admitting her fear at taking the first step towards her crush, but resolving to do it anyway.

Twice’s recent comebacks impressed by staying true to the group’s bubbly girl-next-door image, but imbuing the lyrics with a subtle sense of power not present in their previous title tracks. “Fancy”, like “Me Gustas Tu” and 4Minute’s “What’s Your Name”, portrays a persona unafraid to make the first move on a love interest.

Another artist who reclaimed her girlish image from the clutches of infantilization is IU. After the sickeningly cutesy “Boo” and “Marshmallow”, she gradually took the reins of her music production. Her newfound artistic control resulted in “Twenty-Three”, which retained the signature fairytale/ children’s storybook aesthetics of her past MVs, but focused more on reflecting her transition from girlhood to womanhood.

Pat: In the same way that girl groups using traditionally feminine concepts aren’t disempowering, sexy concepts can be empowering as well. After School epitomizes this: they debuted with a school girl concept for “Ah,” but it never feels disempowering because of the strength of their dancing and the members’ personas.

“First Love” featured pole dancing, which is often sexualized due to its usage in strip clubs, leading to sexual objectification of pole dancers. However, this disregards the physical rigour of pole dancing. It should not be constrained by its stigma and sexual connotations. Not all pole dancers are strippers, as “First Love” proves. The MV emphasizes the group’s core, arm, and leg strength with the way pole dancing is incorporated throughout. Intense athleticism is needed to be able to execute those moves. It was sultry but not sexual, and the eight months of training the members had showed in their execution.

Like GFriend’s powerful and sharp dancing, After School’s use of pole dancing is also empowering despite the traditionally feminine styling. But let’s be real, this is not always the case.

Qing: Just as degrading as the fetishization of young female idols is the sexual objectification of girl groups. The most notorious case is Stellar. “Marionette” arrived in a year that saw a surge in sexiness as the concept of choice. “Marionette” stood out from the crowd even before its release: fans were encouraged to click “like” on their Facebook posts to reveal photos of the scantily-clad members.

The MV followed suit, objectifying the members through low-angle close-ups of their butts and thighs in choreography scenes. Shots zooming in on their naked body parts (the image of milk dripping down Jeonyul’s cleavage comes to mind) encouraged the viewer to take on an objectifying, voyeuristic gaze that sees the female body as a sexual object on display. Their company even wanted them to wear thongs in their next MV, “Vibrato”, emphasising how they were not in control over being sexualised in this fashion.

The treatment of Stellar can be contrasted against that of EXID and Sistar, who are also known for sexy, provocative concepts and dances. Sistar’s “Touch My Body” MV briefly zooms in on their butts, but it mainly focuses on them having fun and performing energetically. The lyrics place Sistar in control as they express their sexual desire frankly, inviting their love interest to touch them.

EXID often make witty, satirical comments on common portrayals of female sexuality. In “Up & Down”, there’s a running motif of dissected female bodies. A masked magician, presumably the one who’s cutting everyone and everything up, studies a manual for piecing these parts back together, but never does it. It’s a playful take on the way women’s bodies are fragmented and objectified in the media. The ending is wickedly subversive: it turns the viewer’s gaze onto stand-ins for male genitalia: a tube man and a banana. When that happens, the magician, who represents the animalistic, predatory male gaze, dies.

Pat: Brown Eyed Girls’ “Sixth Sense” MV is a similar critique on how women are treated in media: Gain has her hands tied while televisions surround her, Jea is chained and drowning as a camera focuses on her, and Narsha is scantily clad with cameras all around her. Even when a woman is giving a voice, there are still chains that bound her, as Miryo’s scenes show. Their recently released “Wonder Woman”, featuring drag performers (in line with the fourth wave of feminism), continues their empowering theme.

Sunmi’s career arc is another example that echoes IU’s. Compare her solos under JYP Entertainment to her current releases. “24 Hours” and “Full Moon” are fine songs, but there was a veneer of sensuality and calm sultriness. Anyone who knows Sunmi will tell you that this is not her. She is fun, energetic, a bit of a weirdo. Her persona is more present in “Gashina” and “Lalalay”’s quirkiness and in “Heroine” and “Siren”’s laid-back funky sensuality.

A similarity between the groups that we see as empowered is that we, the audience, can see their identity. The key to empowerment within this system is a sense of agency and ownership. This delicate balancing act between their identities as women and artists is what makes IU, Sunmi, EXID, Sistar, and Brown Eyed Girls stand out. We can also see the beginnings of this with CLC and now Twice.

Qing: Honestly, K-pop at its core is an act; any image that idols are given has a degree of constructedness and performativity. But this doesn’t discredit the influence of these artists. I think of Yezi’s “Cider” MV: the point isn’t about achieving “authenticity”, but rather giving female idols control over and within their images and music, and using this to push for how the public views them, and by extension, women.

If you enjoyed this article, check out our past op-eds on feminism and women’s issues:

Don’t Look for Your Feminist Heroes in K-pop

Feminism and Girl Groups: Another Look (counterpoint to the above article)

San E’s Feminism is an Ironic Failure

(YouTube [1][2][3]. American Psychological Association, Thought Co, TV Daily, Vox. Lyrics via Kpopquote, Minsarang, Genius [1][2], Popgasa [1][2][3][4], Colorcoded Lyrics [1][2][3].)