Regardless of the nationality, regardless of the race, and regardless of any other taxonomy, the dominance of men over women exists. It is a truth that has been stated and restated, a fact that has been discovered and rediscovered, and a reality that exists universally. Despite the countless movements, rebellions, and victories for change, the world that we exist in today is not that much different from its predecessor in this regard. But the manner in which this dominance and oppression takes place is always and constantly changing.

Regardless of the nationality, regardless of the race, and regardless of any other taxonomy, the dominance of men over women exists. It is a truth that has been stated and restated, a fact that has been discovered and rediscovered, and a reality that exists universally. Despite the countless movements, rebellions, and victories for change, the world that we exist in today is not that much different from its predecessor in this regard. But the manner in which this dominance and oppression takes place is always and constantly changing.

The recently released MV for “Sixth Sense” opens with a shot of a surveillance camera and the succession of the following shots: Jea entrapped and framed by a wreath, Ga In entrapped in a chair and framed by an arch, Miryo entrapped by chains and framed by microphones, and Narsha entrapped in a cage and framed by a room. Though these images are eclectic and different, these images are consistent in their use of entrapment and framing. Each entrapping object is an imprisonment and the framing object is a symbol of the imprisoning entity. And from the camera to the microphones the identity of the imprisoning entity comes into focus. These idols, these entertainers—these women—are imprisoned by their images, by their sounds, by the very entertainment that they provide. And while it is the reality for women in entertainment, the Brown Eyed Girls resist.

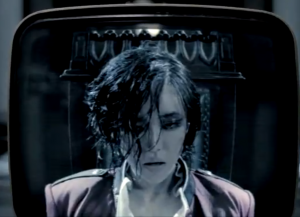

The MV first begins a discussion of the framing of women in entertainment. Ga In’s verse begins with a crane upwards from a television screen of Ga In to the very image framed by the screen. Here Ga In is, hair wet, eyeliner smeared—completely trapped. But trapped by what? She is confined to the chair and the archway but something needs to be said about the use of the television. Though she may be literally trapped by other confinements, she is truly trapped by the screen. The screen is a voyeur and recorder. And while she may be able to escape her literal bounds, she can never escape the screen. The screen forcefully grabs her, frames her in whichever way it wishes, and keeps the image forever.

But the same could apply to a man, right?

Narsha’s verse frames her in a caged room filled with sand and sex. She thrusts, she slides, she stretches. And while it is provocative and sexualized, it is not without purpose. The screen traps women and one of the many ways through which the screen accomplishes this is through their sexualization. Adding to this discussion of the ways in which the screen traps women is Jea’s verse. Jea’s verse brings us to an imprisoning wreath. Restrained, docile, and submissive, another way in which the screen traps women is through oppressive placement. Miryo’s rap brings an interesting complication into discussion. She is in chains and framed by microphones. Even when a woman is given her own voice, her own power, it is still through constraints.

Narsha’s verse frames her in a caged room filled with sand and sex. She thrusts, she slides, she stretches. And while it is provocative and sexualized, it is not without purpose. The screen traps women and one of the many ways through which the screen accomplishes this is through their sexualization. Adding to this discussion of the ways in which the screen traps women is Jea’s verse. Jea’s verse brings us to an imprisoning wreath. Restrained, docile, and submissive, another way in which the screen traps women is through oppressive placement. Miryo’s rap brings an interesting complication into discussion. She is in chains and framed by microphones. Even when a woman is given her own voice, her own power, it is still through constraints.

While their discussions of entrapment offers enough food for thought, their discussions of the entrapment of women in the media by discussing the role of men is this.

There are more men in this MV than there are women and that is not a mistake. The first man that appears before us is the man. He is controlling, dictatorial and- in traditional Big Brother fashion, a voyeur. While the screen is the object of entrapment, who controls the screen, the camera, the microphones? The man, of course. And there are others, in his image, in his mind, in his ideals. And while they struggle to uphold them towards the end of the MV, they follow him in everything that he does. So who is it that uses the screen? While the screen may be entrapping them in a manner of ways, men are responsible for this. They are the members using the camera, both to capture and to view.

They call for resistance against this and thus, resistance is plastered all over the MV. But how so and how to? The Brown Eyed Girls are not pigeons holding themselves into any single, specific image. They are not throwing out the pom poms, the pastel colors, and the oppa screams but they are also not throwing on the leather, the spikes, and the attitude. From fierce, to sexy, to beautiful, to whatever they will—they are doing what they want, how they want. Not because anyone told them to—especially the screen and the man behind the screen.

They call for resistance against this and thus, resistance is plastered all over the MV. But how so and how to? The Brown Eyed Girls are not pigeons holding themselves into any single, specific image. They are not throwing out the pom poms, the pastel colors, and the oppa screams but they are also not throwing on the leather, the spikes, and the attitude. From fierce, to sexy, to beautiful, to whatever they will—they are doing what they want, how they want. Not because anyone told them to—especially the screen and the man behind the screen.

The thesis and the argument are strong and provocative. But it also has its problems. While their efforts are commendable, they have not escaped the very thing that they are arguing against. They are resisting the screen and the man, but are they not using the screen to propagate their message? Are they not still victims of the man? What gives them the credibility to beget such an argument?

While I have no answers to these questions, their presentation of the issues for females in entertainment is artfully created. The media traps women in specific representations. And not through their own agency but through the agency of men. And their solution for this problem involves the development of their own agency—the agency of women.

While I have no answers to these questions, their presentation of the issues for females in entertainment is artfully created. The media traps women in specific representations. And not through their own agency but through the agency of men. And their solution for this problem involves the development of their own agency—the agency of women.

Thinking about the agency of women is a progressive thought, especially in Korean entertainment where men truly do dominate. But it is not impossible and something that future entertainers should continue think about and expand upon.