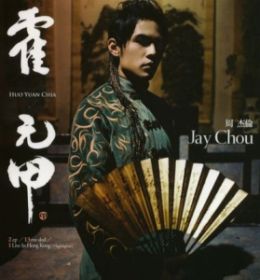

Jay Chou. You may not know him, but over a billion Chinese people recognize him as the father of modern Chinese pop music. He’s been given much credit for ushering in a new era of pop music that creatively blends the sound of Western music with that of classical Chinese aesthetics. Not only is he a talented and multi-faceted megastar in the Chinese-speaking world, he’s also built an entire enterprise through singing, composing, acting, directing, and endorsements. Many consider him to be the current “king of Chinese pop music,” and rightfully so.

Jay Chou. You may not know him, but over a billion Chinese people recognize him as the father of modern Chinese pop music. He’s been given much credit for ushering in a new era of pop music that creatively blends the sound of Western music with that of classical Chinese aesthetics. Not only is he a talented and multi-faceted megastar in the Chinese-speaking world, he’s also built an entire enterprise through singing, composing, acting, directing, and endorsements. Many consider him to be the current “king of Chinese pop music,” and rightfully so.

“Gangnam Style.” Not much to say here that hasn’t already been said. It’s won over YouTube, the charts, our neighbors, family, relatives, and pretty much anybody in the world who has access to some form of video streaming device. Surprisingly, for a hit of such unprecedented magnitude, it’s received very little backlash. Unlike the song it overtook on YouTube for the most views of all time, Justin Bieber’s “Baby” who’s current likes to dislikes ratio is still well under 1 to 2, Psy’s song is unanimously liked (5,834,357 likes to 392,640 dislikes, or 93.7% likes at the time of writing). It’s generating a normal ratio of likes to dislikes amongst songs which have incredibly high view counts due to their worldwide popularity, averaging a slightly higher ratio of likes to dislikes than YouTube’s third most liked video, Jennifer Lopez and Pitbull’s “On the Floor” (1,111,790 likes to 87945 dislikes, or 92.7% likes).

Statistics aside, it’s fair to say that “Gangnam Style” has received very little resistance from any form of opposition since its inception, for the most part gaining uninterrupted universal acceptance. Although Psy’s history has been scrutinized as of late (a topic for another day), and his popularity in the West has put into question the phenomenon’s socio-cultural impact, there’s been virtually no direct objections against the song itself (unless you count this). So who would have thought that the first direct punch would come from no other than Jay Chou?

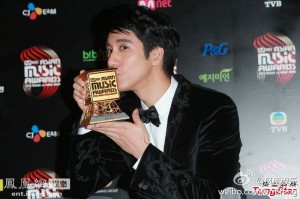

There’s been much construal over what was actually said with English translations providing headlining interpretations based on inferences of his actual statements. From my own research, it’s clear that Chou commented on the Korean Wave on at least two separate occasions at the 10th annual Baidu (China’s equivalent of Google) Awards. During an acceptance speech, he thanked everyone for supporting Chinese music, even if it’s not his own, and encouraged the audience to not let the Korean Wave overtake the Chinese Wave. Later during a backstage interview, Chou stated that the Korean Wave is currently very strong and in order to not let the Korean Wave overtake the Chinese Wave, all artists must unite and stop doing “Gangnam Style.” Since it’s quite evident from the clips of his acceptance speech and backstage interview that there weren’t any direct prompts from the press which could have elicited such comments, it can be inferred that it was Chou’s personal intention to use the platform to make his statements.

There’s been much construal over what was actually said with English translations providing headlining interpretations based on inferences of his actual statements. From my own research, it’s clear that Chou commented on the Korean Wave on at least two separate occasions at the 10th annual Baidu (China’s equivalent of Google) Awards. During an acceptance speech, he thanked everyone for supporting Chinese music, even if it’s not his own, and encouraged the audience to not let the Korean Wave overtake the Chinese Wave. Later during a backstage interview, Chou stated that the Korean Wave is currently very strong and in order to not let the Korean Wave overtake the Chinese Wave, all artists must unite and stop doing “Gangnam Style.” Since it’s quite evident from the clips of his acceptance speech and backstage interview that there weren’t any direct prompts from the press which could have elicited such comments, it can be inferred that it was Chou’s personal intention to use the platform to make his statements.

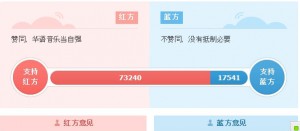

While this may not be big news in the West, it’s made quite the buzz amongst Chinese netizens. In a recent poll conducted by a Chinese microblogging site, about 80 percent of 90,781 voters stated they agreed with Chou’s statements while the remainder voted that his statements were going too far. Moreover, the poll has apparently generated over 100 million comments. Needless to say, Chou’s words carry a lot of weight in much of the Chinese-speaking world. Plus, he’s accomplished what many in K-pop have yet to do – break into the Chinese market. In fact, he created the market.

Chou’s success and initial rise in popularity is largely attributed to his appeal to a new generation of youth growing up in an economically remodeled China. Fresh on the heels of economic reforms in the late 80s and 90s, Chou entered the market at a time when China was coming to terms with an ever growing influx of Western influence which had much of an effect on transforming the culture of Chinese youth. Considering the internal angst that comes with embracing the appeals of Western culture while resisting an erosion of traditional Chinese culture, Chou brought in his music a suitable blend of both which quickly filled the void of young Chinese people who desperately sought an image that could resonate with the new without stripping away the old. Hence, Chou began a trend of combining Western elements of music such as pop, rock, hip hop, and R&B with Chinese instrumentals produced by the erhu, qin, and other classical Chinese instruments.

Other than the classically-inspired beats, his music contains various traditional Chinese elements. His well-known lyricist, Vincent Fang, has been known to produce lyrics in the form of classical Chinese poetry. Chou’s themes and concepts touch upon relevant topics of Chinese culture. Through his songs, he’s alluded to the grandeur of ancient Chinese dynasties, paid tribute to a fictional historical martial arts hero (who Jet Li portrays in the film Fearless), promoted Confucian values of filial piety, and addressed modern issues of urbanization, drug addiction, domestic violence, and the education system. Through his focus on integrating Chinese elements into Western-influenced pop music, he’s created what is known as the “China Wind,” a term much like “Hallyu” in that it describes the current wave of Chinese pop music that has swept not only China and Taiwan, but has also found a measured level of success throughout Asia, putting it in direct competition with K-pop.

Other than the classically-inspired beats, his music contains various traditional Chinese elements. His well-known lyricist, Vincent Fang, has been known to produce lyrics in the form of classical Chinese poetry. Chou’s themes and concepts touch upon relevant topics of Chinese culture. Through his songs, he’s alluded to the grandeur of ancient Chinese dynasties, paid tribute to a fictional historical martial arts hero (who Jet Li portrays in the film Fearless), promoted Confucian values of filial piety, and addressed modern issues of urbanization, drug addiction, domestic violence, and the education system. Through his focus on integrating Chinese elements into Western-influenced pop music, he’s created what is known as the “China Wind,” a term much like “Hallyu” in that it describes the current wave of Chinese pop music that has swept not only China and Taiwan, but has also found a measured level of success throughout Asia, putting it in direct competition with K-pop.

Chou’s influence upon the Chinese-speaking world goes beyond that of a celebrity and entertainer. He is not only a staple of Chinese pop music and entertainment; he’s a symbol of Chinese pride. Since its economic rebirth and rise in the global economy, China has greatly emphasized its celebrated figures in the global Chinese diaspora, adoring them as indicators of China’s return to prominence on the world stage after centuries of being mocked and defeated by foreigners. Much of this was on display in the 2008 Summer Olympics as many of China’s gold medalists became immediate national heroes.

Literally calling itself the “middle kingdom,” China embraces the accomplishments of Chinese people worldwide even if they are not Chinese nationals. Leehom Wang and Jeremy Lin are examples of famous Chinese figures who have been adopted (not literally) and embraced by China as symbols of pride despite the fact that they were born and raised in nations outside of the mainland. Although his birth and upbringing originate in Taiwan, Chou’s pioneering of the China Wind has made him an ethnic if not a national treasure to Chinese people throughout the regions surrounding and influenced by China. In other words, to the large majority of the Chinese-speaking population in Asia who have yet to succumb to the Korean Wave, Chou is the face of their prescribed pop music industry. He is to Chinese pop music what SNSD, Super Junior, and Big Bang is to K-pop, combined! So who else is better suited to speak out against “Gangnam Style” and the onslaught of the Korean Wave in relation to Chinese pop music?

Literally calling itself the “middle kingdom,” China embraces the accomplishments of Chinese people worldwide even if they are not Chinese nationals. Leehom Wang and Jeremy Lin are examples of famous Chinese figures who have been adopted (not literally) and embraced by China as symbols of pride despite the fact that they were born and raised in nations outside of the mainland. Although his birth and upbringing originate in Taiwan, Chou’s pioneering of the China Wind has made him an ethnic if not a national treasure to Chinese people throughout the regions surrounding and influenced by China. In other words, to the large majority of the Chinese-speaking population in Asia who have yet to succumb to the Korean Wave, Chou is the face of their prescribed pop music industry. He is to Chinese pop music what SNSD, Super Junior, and Big Bang is to K-pop, combined! So who else is better suited to speak out against “Gangnam Style” and the onslaught of the Korean Wave in relation to Chinese pop music?

Although Chinese pop music may not be as popular as K-pop internationally, it’s still a thriving industry that caters to the likes of Chinese speakers worldwide. It needs not market itself as ambitiously to the entire world because it’s secured a large enough market in Taiwan and China to be self-sustaining. With the continued economic development of China, that market is only expanding.

Meanwhile, K-pop is viewed as a foreign presence infringing on a part of the Chinese market. This isn’t the first incidence a Chinese artist has raised concern over the Korean Wave’s intrusion into a market that was thought to have been secured by Chinese pop music, and it certainly won’t be the last. Unlike Japan, China’s market has never been friendly to foreign acts, especially one that campaigns so vigorously to install itself as a permanent fixture. Having realized the growing presence of K-pop in his native Taiwan and parts of China, Chou is utilizing his status as a leader of the industry to invoke a sense of ethnic pride in promoting Chinese pop music. When the reporter asked whether we should be doing “Jay Chou style” in response to Chou’s comments, he jokingly replied with “no, Chinese style.” As the biggest ambassador of Chinese pop music, he is entitled to rally his fellow artists.

Meanwhile, K-pop is viewed as a foreign presence infringing on a part of the Chinese market. This isn’t the first incidence a Chinese artist has raised concern over the Korean Wave’s intrusion into a market that was thought to have been secured by Chinese pop music, and it certainly won’t be the last. Unlike Japan, China’s market has never been friendly to foreign acts, especially one that campaigns so vigorously to install itself as a permanent fixture. Having realized the growing presence of K-pop in his native Taiwan and parts of China, Chou is utilizing his status as a leader of the industry to invoke a sense of ethnic pride in promoting Chinese pop music. When the reporter asked whether we should be doing “Jay Chou style” in response to Chou’s comments, he jokingly replied with “no, Chinese style.” As the biggest ambassador of Chinese pop music, he is entitled to rally his fellow artists.

The reason there’s been issues raised over what he’s said is because his statements have been largely misinterpreted. The spin on many Western K-pop sites are framing them as a direct reproach against “Gangnam Style” and the Korean Wave, labeling him as a hypocrite for his K-pop influenced blonde hair and how much he looks like 2PM’s Wooyoung. In an attempt to create buzz, these sites have taken his words out of context, made invalid inferences, and have thus completely blown the issue out of proportion. Please allow me to reinstate reason.

First of all, it’s quite evident from his actual words that the people he is telling to stop it with the “Gangnam Style” are artists, but many are interpreting it as a cry for all people to stop doing “Gangnam Style.” He is not asking Chinese people or any individual to stop liking “Gangnam Style” or the Korean Wave. He’s asking other Chinese artists to stop promoting K-pop by doing “Gangnam Style.” In turn, he is implying that Chinese artists should focus on bettering their own music to combat the Korean Wave. He is not simply lashing out against K-pop or “Gangnam Style.”

Secondly, he is promoting Chinese pop music at a Chinese awards show. He’s raising awareness of the Korean Wave’s advance into the Chinese market and he’s urging other Chinese artists to be wary of how their actions are hurting their own industry. Furthermore, he is not the first person to do such a thing. Another popular Chinese artist, Show Luo, made a similar statement most recently by not participating in the “Gangnam Style” dance during the 12th annual Global Chinese Music Awards. When asked about it, Luo clearly stated that he was doing so in support of Chinese music. Neither artist is protesting for his own benefit or attempting to belittle K-pop, but they are insinuating a sense of ethnic pride through their actions. They’re sending the message that Chinese artists should come together in support of one another to create an industry that is strong enough to suppress what they believe is a temporary yet strong offensive from the Korean Wave.

Secondly, he is promoting Chinese pop music at a Chinese awards show. He’s raising awareness of the Korean Wave’s advance into the Chinese market and he’s urging other Chinese artists to be wary of how their actions are hurting their own industry. Furthermore, he is not the first person to do such a thing. Another popular Chinese artist, Show Luo, made a similar statement most recently by not participating in the “Gangnam Style” dance during the 12th annual Global Chinese Music Awards. When asked about it, Luo clearly stated that he was doing so in support of Chinese music. Neither artist is protesting for his own benefit or attempting to belittle K-pop, but they are insinuating a sense of ethnic pride through their actions. They’re sending the message that Chinese artists should come together in support of one another to create an industry that is strong enough to suppress what they believe is a temporary yet strong offensive from the Korean Wave.

As for attacking Chou for sporting a blonde, that in itself is a shallow argument. Korean artists by no means own the right to blond hair. Neither do Caucasians or any other race or ethnicity. The underlying allegation behind this criticism is that Chou is a hypocrite for having adapted elements of K-pop in his own style and music. Whereas the former insinuation is clearly reactionary name-calling, the latter is for the most part true. He’s not only adapted elements of K-pop, but also that of pop music from all around the world, sampling heavy doses from American pop and even from Latin pop.

That is not to say that K-pop doesn’t do the same exact thing. The presence of autotune, electro beats, and a beastlier image in Chou’s recent musical styling can be said to be of K-pop influence, but those elements also originated elsewhere and have in turn influenced K-pop over the years. To say that these elements are specific only to K-pop is utterly false. Pop music is a global product and the reason Chou’s music has maintained its popularity for well over a decade is because of his ability to integrate Chinese elements within current pop influences. He is not copying K-pop or any other pop music. Like any other successful artist, he is adapting his music to fit the trends of modern pop. As a leader of his industry, he is encouraging other artists to also do the same with their music in order to stay competitive with the ever adapting mechanisms of K-pop. He isn’t implementing an ethnic, national, or linguistic boundary on music, but attempting to inspire a unity amongst Chinese artists to not lose sight of themselves in an industry that is evolving faster than it’s ever had.

That is not to say that K-pop doesn’t do the same exact thing. The presence of autotune, electro beats, and a beastlier image in Chou’s recent musical styling can be said to be of K-pop influence, but those elements also originated elsewhere and have in turn influenced K-pop over the years. To say that these elements are specific only to K-pop is utterly false. Pop music is a global product and the reason Chou’s music has maintained its popularity for well over a decade is because of his ability to integrate Chinese elements within current pop influences. He is not copying K-pop or any other pop music. Like any other successful artist, he is adapting his music to fit the trends of modern pop. As a leader of his industry, he is encouraging other artists to also do the same with their music in order to stay competitive with the ever adapting mechanisms of K-pop. He isn’t implementing an ethnic, national, or linguistic boundary on music, but attempting to inspire a unity amongst Chinese artists to not lose sight of themselves in an industry that is evolving faster than it’s ever had.

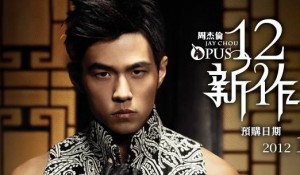

On that note, Chou’s new album, Opus 12, will be released later this month. Check out his new single “Red Dust Inn” to see why he is the face of Chinese pop music. How does the China Wind feel in comparison to the Korean Wave?

(Sina, UC San Diego, Diva Asia, YouTube 1, 2, 3, 4, Mnet, Images via Weibo, Jay Chou’s Facebook, Mnet, JVR Music, JYP Entertainment, Gold Typhoon Group, Baidu)