In the world of K-pop exists fans of nearly every type. There are shy fans, passionate fans, jealous fans, obsessive fans, and even saesang fans. Many of us know all too well how many rampant, infatuated teenage girls as well as hormonal, lovestruck teenage boys swoon and worship their beloved idols and idol biases as if life had no other meaning.

In the world of K-pop exists fans of nearly every type. There are shy fans, passionate fans, jealous fans, obsessive fans, and even saesang fans. Many of us know all too well how many rampant, infatuated teenage girls as well as hormonal, lovestruck teenage boys swoon and worship their beloved idols and idol biases as if life had no other meaning.

In the world of K-entertainment, much like with entertainment industries around the world, it almost too easy for plebeians of every age and race to fall madly in love for glittering, airbrushed idols and their music. But as we consider the kinds of fans that constitute these ever-growing fandoms, both at home and on a global scale, it may be worth taking note of the uncle fans.

“Ahjusshi,” “samchon,” “uncle”: all are used in roughly the same context to describe older male fans, those particularly over the age of 30. And while there is certainly nothing wrong with being an uncle fan, one can’t help but ask, why call yourself an “uncle”? Does it make a difference what kind of fan you are whether you are 30 or 13? Can’t an older person, an older male, enjoy modern day bubble gum pop the way a young person can rejoice in classical music or jazz without being labeled as another breed of fan? Sure, perhaps in an ideal, sexual tension-free world, such music preferences would be all too benign for an uncle fan. But let’s be real here.

First, I want to establish something: there is nothing wrong with being male, above 30 years old, and a fan of K-pop. Music choice is simply a matter of preference, and anyone should be free to enjoy music that appeals to them, however it may appeal to them. Also, I do not believe that every uncle fan out there can be classified in a way I will later discuss. As in any fandom, there are the good and there are the bad. For the sake of discussion, we will be exploring primarily the bad, in context of K-pop today.

Within that context, the widespread existence of uncle fans brings up several issues, none perhaps more imperative than the fostering of sexual tension in older men for much younger women. And while it would be fair to say that every human being feels desire, and is vulnerable to mediums that provoke desire, the ethics arguments becomes a little skewed when samchons and pop idol princesses are thrown into the mix.

The first and greatest point to make is the use of word and meaning of “uncle” in terms of being a fan of young women. Because of the nature of K-entertainment and it’s tendency to beautify and cutesify its female idols to portray an approachable, vulnerable, and young-looking demeanor, the idea of having an older male fandom that throngs to these idols implies that with these mature male fans comes all their mature feelings.

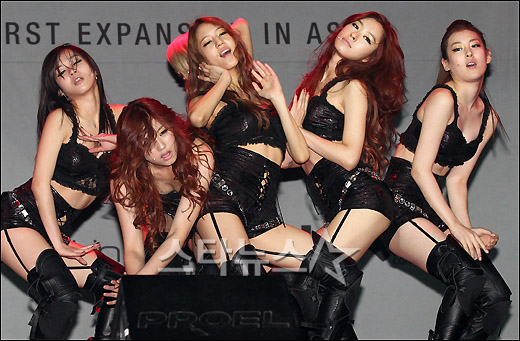

Whereas your average teen male fan may be running off spikes in hormones and adrenaline, the 30 or 40 year old male fan could very well be running off real, mature, sexual stimulation. Putting those words together alongside the image of female teenage idols waving pom-poms and wearing infinitely short shorts would make anyone, old, young, fan, or anti-fan, feel a bit uneasy.

The reality of this fandom, though, is that they are not labeled simply as older men. They’re “uncles.” So while sexual tension may or may not exist within this fandom, the term “uncle” effectively masks any such feelings that could exist with its familial connotation. Suddenly instead of an older man looking lustfully down upon little IU or precious Taeyeon, or, God forbid, darling Sohee, these men are shielded from scorn and contempt from society at large for lusting for a young girl by the term “uncle.” Not to say by any means that this is the very definition of the uncle fan, for an uncle fan could be just as benign and endearing as others are lustful. However, it is hard to deny that there exists a number of uncles fans that smother sexual feelings beneath the label ‘uncle fan.’

Yeran Kim, an Associate Professor at Kwangwoon University, couldn’t have elaborated on the topic better in her essay Idol republic: the global emergence of girls industries and the commercialization of girl bodies.

As Samchon in Korean refers to one’s parent’s brother, this name implies the middle-aged men’s care for their young nieces. Once this familial setting is built up, a relationship between male viewers or self-claimed Samchon fans is restructured in the complicit relationship between uncle and little nieces. Accordingly, the male’s gaze at young female bodies is legitimized and normalized as the voluntary support and pure love of uncles for their nieces. Under the identity of uncle, they can deny the sexual aspect of what they see and insist on appreciating merely the pure surface of pretty children.

But before we point the finger at the older men who have gone head over heels for girls between the ages of 16 and 25, let’s consider both sides of the argument. Uncle fans may be responding to the charms of female pop idols, but aren’t K-entertainment agencies equally at fault for, well, establishing the female idol image and selling it to a public audience? And of all the things agencies can use to market their idols, more often than not, these agencies will stick to the image that sells to audiences young and old–the image of the cute yet deceptively sexy baby face, some more obvious than others.

So while, yes, the question still remains “why all the uncle fans,” the question could also be “why does mainstream K-pop sell cute sex that rakes in uncle fans?” Perhaps it was inadvertent that cute was eventually abstracted to sexy and began to appeal to older and older audiences. Or perhaps it wasn’t. It’s hard to say. After all, K-entertainment, however saturated it is with women, is business run by men.

Again, let me reiterate how not every uncle fan can be defined by the near-pedophiliac nature with which some older male fans approach younger female idols. Just like how every K-pop fan is not necessarily a saesang fan, every uncle fan is not necessarily a creepy uncle fan. The uncle fans that use their label to indulge in sexual stimulation, however, do undoubtedly exist, and without doubt raise some serious ethical questions about entertainment and the concept of beauty in Korea.

And while perhaps the ethics questions can be explained through elaborate discussion, and the question posed against why agencies sell what they sell can be answered with a short tirade on capitalism, the question ‘why the uncle fans’ can never really be concretely answered.

And while perhaps the ethics questions can be explained through elaborate discussion, and the question posed against why agencies sell what they sell can be answered with a short tirade on capitalism, the question ‘why the uncle fans’ can never really be concretely answered.

This is because there will always be uncle fans whose endearment reaches out to the cute female pop idols and uncle fans who secretly lust after female idols. And though it is possible that this fandom phenomena may exist elsewhere in the world as well, I personally can’t say I have seen it so fervent and perhaps even so widely accepted in any other place but Korea.

While there is no harm in having an uncle fandom, there is also great potential for harm. Harm in the sense that it may question the integrity of the K-pop industry and project poorly on K-entertainment as it is seen elsewhere in the world. But just as it may do these things it also may never do these things. The uncle fandom, thus, is rather confounding and creepy at times, as it presents itself masked behind the understanding of the word ‘uncle’ though it may foster sexual tensions with considerable age gaps. Because an uncle fandom could easily be a round up of supportive fathers, if could also mean a batch of sex-crazed weirdos who prey on the products of entertainment. This dual nature and odd character of the uncle fandom therefore makes the question of the fandom’s existence, persistance, and growth particularly difficult answer. Still regardless of the duality of the topic, looking out into a crowd of older men cheering on singers like SNSD, 4minute, and IU forces one to wonder, ‘Why the uncle fans?’

(Yeran Kim via Taylor and Francis Online, thegrandnarrative, LOENENT)