Just a few days ago, we were blindsided by a wave of dating rumors, first brought on by the discovery of Kim Woo-bin’s two year relationship with model Yoo Ji-Ahn.

Just a few days ago, we were blindsided by a wave of dating rumors, first brought on by the discovery of Kim Woo-bin’s two year relationship with model Yoo Ji-Ahn.

As with most breaking news on celebrity relationships, the reactions across cyberspace were varied. Some cheered. Some cried. However, perhaps unsurprisingly, a minority of fans felt pity for the person they considered Kim Woo-bin’s other half: Lee Jong-suk.

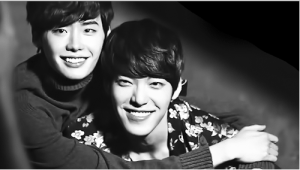

Kim Woo-bin and Lee Jong-suk have a well-storied bromance that stemmed from their performances in the popular drama “School 2013,” in which their characters built a close friendship. Both followed through on their characters’ relationship while promoting the drama, using interview appearances to flatter the other and emphasize how close they were.

This is of course the formulaic recipe for a ship to be born.

Shipping — pairing of two or more characters together, usually to suggest a romantic relationship — has been discussed often on Seoulbeats and elsewhere, universally accepted as as a natural sub-activity of fandoms. In fact, a bit of time on the internet would clue you in that it’s not at all unique to the Korean entertainment scene.

The culture of shipping has been around at least since the 1960s, with the popular television show “Star Trek,” and it can be found in music, movies, and books as well. Whether you’re a participator, spectator, or protester, shipping is far from being a fad.

Shipping doesn’t come without complications, though. This is especially true when the people being paired aren’t fictional, the typical case with shipping in Korean entertainment fandoms. For K-drama actors and K-pop idols, the practice can become a professional and personal setback.

Having a fanbase is critical to success in the music and acting fields, and the pressure to please fans and keep their support encourages appeasing the OTP-supporters that just so happen to be fans. This brings us to the sometimes burdensome practice of fanservice.

As previously stated, promotional material for School 2013 had been chock full of fanservice from both Woo-bin and Jong-suk; much of their mutual affection had been ramped up with sensational sound bites to appease the show’s growing shipping contingent.

It’s this essence of performance friendship that cheapens the idols’ actual relationships. To have a normal conversation with someone behind doors and to have to pseudo-kiss, cuddle with, and/or excessively touch this person when cameras are around can create an awkward divide between personal and public identity when it isn’t necessary.

What isn’t necessary as well is the indirect statement about genuine homosexual relationships, the ones that obviously wouldn’t get the same reception if separated from this sensationalized context.

Yet, the cycle goes on and on.With some acts of fanservice, idols aren’t just treating their friendships as performances; they’re indirectly treating sexual orientation as a performance, and the implications can be hurtful for those who aren’t pretending to be attracted to the same sex for the sake of entertainment.

Some fans still show up to Jaejoong’s fanmeets and concerts with Yunjae signs, despite the accounted efforts from C-JeS Entertainment persuading fans to leave them at home. Others still shout Jaejoong’s name to Yunho when he’s onstage. When Jonghyun and Key perform fanservice these days, nearly a five-year long practice for them by now, they look bored, sometimes even fatigued. And in the acting world with Kim Woo-bin, he often can’t go one interview without being asked about Lee Jong-suk in some capacity.

It’s a chore to fake or hyperbolize a relationship, and even sillier to have to stake your success as an entertainer on it. One can guess that male K-pop groups deal with this issue most often, and it hasn’t cooled down over time. Most groups have established member pairings that are popular, either by fan invention or by the encouragement of groupmate behavior.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S_YBqBE8KKU]One might ask the question: what generally comes first, shipping or fanservice? It depends. But nonetheless, it all stems back to the implicit power of shipping culture in the entertainment industry, and by this point, it can’t really be tamed. This is to be expected from both sides — fans and idols.

For Kim Woo-bin to be frequently associated with his former costar, even months after the close of School 2013, is testament to the greater issue of the media indulging the pairing and giving Kim Woo-bin no arena to branch out.

As a rookie actor who’s still carving out his own identity in the industry, how difficult it must be, to live in perpetual comparison to someone else?

Maintaining a friendship with Lee Jong-suk shouldn’t have a direct consequence of having to confirm it ad nauseam, so that the OTP is kept alive for shippers. And he most certainly shouldn’t be made to feel guilty about his relationship because it doesn’t meet fan expectations.

To fans, shipping may not be that serious, and most of the time it isn’t. There’s nothing wrong with playing it up — even Robert Downey Jr. and Jude Law got a kick out of it when they promoted the Sherlock Holmes screen franchise. When boundaries aren’t crossed, shipping is generally done in good fun. But when the people involved have to doublethink every interaction they have, navigate reports that their real-life significant others are getting hate from fans, or even tie the longevity of their careers to constant association with their shipping partners, the whole activity doesn’t seem so carefree anymore.

This is exactly why shipping needs to stay in the stratosphere of fans and not constantly in front of idols’ faces. Like anyone else, they have a job to do, and despite its merits, an exacerbated form of shipping could be a loud, counteractive statement against a celebrity’s advancement. We wouldn’t want shipping to get in the way of the good stuff, would we?

(MWave, YouTube, Images via KBS)