It is no secret that the exchange of entertainment between South Korea and Japan is tied up in, and often symbolic of, a complex history between the nations. Yet as K-pop continues to expand internationally, Japan remains an important market for South Korean music exports. Therefore, it comes as no surprise that it has become commonplace, if not outright expected, for K-pop groups to debut in Japan. Recently, Stray Kids announced that they will make their official Japanese debut in March 2020. This is a postponed date due to a recent trade issues between the nations, an example that highlights how entertainment is a form of soft power. Additionally, TXT have announced their Japanese debut for the new year.

However, the act of translating a Korean work into a Japanese version involves many steps, including the translation between languages, the introduction of a new style or aesthetic, the re-release of a song or video, and a whole new marketing and promotional cycle. A successful Japanese debut by Korean artists must master these simultaneous translations to appeal to growing international fanbases.

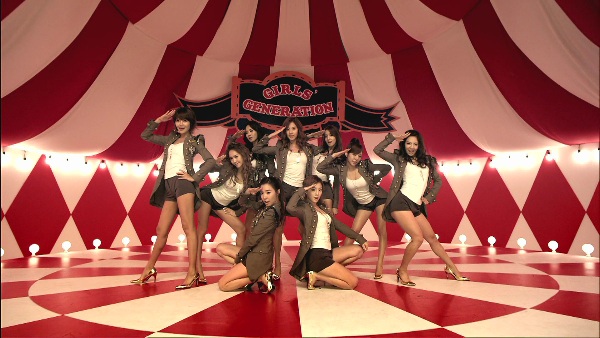

The phenomenon of Korean entertainment in Japan is a relatively new one. BoA became the first Korean singer to top Japanese charts in 2002 with Listen to My Heart, her debut Japanese album. BoA’s success paved the way for second-generation groups including Girls’ Generation, KARA, and BIGBANG to achieve success during the early 2000’s. These groups reached new heights in the market and became regular fixtures in Japanese media, appearing on variety shows and advertisements, for example.

The success of these groups is even more impressive in the context of J-pop and Japan’s own idol culture. A key difference between K-pop and J-pop is their sound and production. While Korean music tends to follow Western trends, from European electro house to American R&B and beyond, J-pop has featured relatively less sonic experimentation. Patrick St. Michel of The Atlantic argues thatJ-pop has remained “basically unchanged for the past two decades. Japanese music plays it safe, resulting in a bland popscape where artists have very little opportunity to expand internationally.” This still fails to account to for the prominence of mainstream Japanese artists, who still dominate their domestic market even when compared to Korean artists.

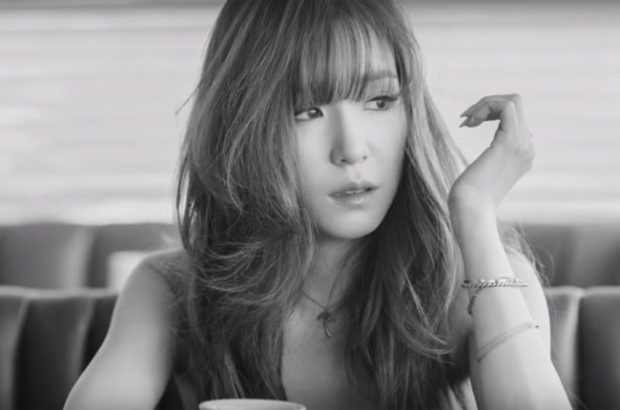

Image is another key difference. In general, female idol groups in Japan are encouraged to look youthful and cute to appeal to a primarily male “otaku” audience (the closest Korean equivalent being ‘ahjussis’). The Japanese concept of “kawaii” is the standard to which idols are visually held. On the other hand, female South Korean idols appear more mature and sexually appealing. This difference is apparent when groups re-purpose works for the Japanese market.

For example, Girls’ Generation’s 2010 Korean video for “Genie” centers around an male figure as he is led around what appears to be the genie’s lamp by members. In the 2012 Japanese video for the song, this male figure is reimagined as a young boy (coincidentally, Exo’s Chanyeol pre-debut) discovering and dusting off the lamp. In terms of styling, the Korean version features more skin and flirting with the male figure, who is almost entirely absent from the Japanese version.

A more stark comparison is T-ara’s 2009 video for “Bo Peep Bo Peep.” The video shows a member hooking up with a guy in various locations, from an elevator to a cab. In contrast, the male figure is absent in the Japanese video for the song; in his place are scenes of the members dancing and playing around in cat ears, which seems tame by comparison. In general, and especially in the early 2000s, the sexuality of the Korean original gets replaced by an image that aligns more closely with Japan’s idol culture and aesthetics.

When idols and groups seek to extend their promotions outside of Korea, a number of “translations” occur. Most obvious is the linguistic translation between Korean and Japanese, in which Korean songs are released in Japanese. Recently, (G)I-DLE made their Japanese debut and performed a showcase in Tokyo. The group’s Korean debut was in May 2018 with the debut track “Latata” and their Japanese debut came about a year later with a mini album of the same name that included a translation of “Latata.” TXT’s upcoming Japanese debut will capitalize on this linguistic difference; the group will release an album featuring Japanese renditions of “Crown,” “Run Away,’ and “Angel or Devil.” In the past when other groups have used similar translational tactics, it has led to lackluster responses. The re-release of Korean songs in the Japanese language often disappoints in both quality and novelty.

One way groups have combated this response is by taking different promotional tactics. For instance, Ateez recently released their debut Japanese album, Teasure EP. Extra: Shift the Map. As part of their debut, the group released a Japanese version of a fan favorite B-side track, “Utopia.” Other groups have opted to release entirely original Japanese albums and mini albums. Recently, The Boyz made their Japanese debut with their first original Japanese mini album Tattoo, which features six original Japanese songs. Overall, it seems that Korean artists are increasingly releasing new works in Japanese in order to appease fans with new content beyond Korean to Japanese translation of title tracks.

The opposite flow of musical entertainment (from Japan to Korea) is a less examined phenomenon. There are a variety of reasons that Japanese record companies have put less emphasis on exporting their music to other markets. One such reason is that, in contrast to other countries in the region, Japan more strictly monitors copyright laws and piracy. Another reason has to do with the rise of new technologies in the early 2000s, which Japanese record labels were slow to adopt, including iTunes and YouTube. This is surprising when one considers Japan’s hegemony in the region and its successful global export of other cultural products, like manga and anime.

Overall, groups who debut in Japan do so to expand their international fanbase, but need to understand the differences between markets in order to achieve success. Fans both within and outside of Japan expect a level of novelty when it comes to Japanese debuts – new concepts and music are essential to a group’s success. As Stray Kids and TXT make their debuts in the country, they have a real opportunity to further develop their discographies and elaborate upon their concepts as groups.

Readers: What are some of your favorite Japanese debuts?

(Japan Times. Images via JYP Entertainment, SM Entertainment, MBK Entertainment, and KQ Entertainment)