August 15th marks in the Korean calendar Gwangbokjeol, or Liberation Day, which commemorates the ending of the Japanese colonial rule and the creation of the South Korean government. The President usually conducts a ceremony, either at South Korea’s Independence Hall or at the Sejong Center. The main attraction of the holiday is the South Korean flag that can be spotted practically everywhere. Outside the Songpa-gu Office, thousands of flags were mounted in the trees for this particular day. Broadcast channels air special programs to make sure the event doesn’t pass unnoticed and citizens have the opportunity to participate in various parades. In short, it’s typically celebrated as a national holiday.

August 15th marks in the Korean calendar Gwangbokjeol, or Liberation Day, which commemorates the ending of the Japanese colonial rule and the creation of the South Korean government. The President usually conducts a ceremony, either at South Korea’s Independence Hall or at the Sejong Center. The main attraction of the holiday is the South Korean flag that can be spotted practically everywhere. Outside the Songpa-gu Office, thousands of flags were mounted in the trees for this particular day. Broadcast channels air special programs to make sure the event doesn’t pass unnoticed and citizens have the opportunity to participate in various parades. In short, it’s typically celebrated as a national holiday.

But this year, this very day’s celebration was tinted by political turmoil. Around the controversial Olympics and amidst the unfinished comfort women issues, Lee Myung-bak decided to visit the Liancourt Rocks (Dokdo/Takeshima islands), a disputed territory between Japan and South Korea, in a move that was similar to Medvedev’s visit to the Kuril Islands in 2010. Moreover, he asked the emperor for an official apology to the South Koreans that have suffered during the colonial rule. Japan responded much like it did in 2010, by calling Japan’s ambassador in South Korea back to Tokyo.

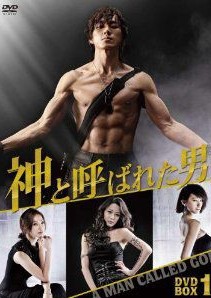

Leaving the politics to the parties involved, the increasing tension affected also the non-political space. Actor Song Il-gook, together with a handful of volunteers, decided to swim from the South Korean shore to the Liancourt Rocks to make this day unforgettable. As a result, Japanese TV channel BS Nippon cancelled the K-drama A Man Called God because of the main actor’s gesture. Football-player Park Jong-woo ran with a banner saying that the Dokdo Islands belong to South Korea after his team’s victory over Japan. This might jeopardize another football-player’s near future, Kim Hyun-sung, whose 5-months loan deal with Shimizu S-Pulse (a Japanese football club) was strongly criticized.

Leaving the politics to the parties involved, the increasing tension affected also the non-political space. Actor Song Il-gook, together with a handful of volunteers, decided to swim from the South Korean shore to the Liancourt Rocks to make this day unforgettable. As a result, Japanese TV channel BS Nippon cancelled the K-drama A Man Called God because of the main actor’s gesture. Football-player Park Jong-woo ran with a banner saying that the Dokdo Islands belong to South Korea after his team’s victory over Japan. This might jeopardize another football-player’s near future, Kim Hyun-sung, whose 5-months loan deal with Shimizu S-Pulse (a Japanese football club) was strongly criticized.

Kim Tae-hee’s controversy and Song Il-gook’s A Man called God shed light over an issue rather difficult to tackle. In the context of strong anti-Japanese/anti-Korean feelings, what’s the probability for an unabridged communication between the two countries? Furthermore, Tae-hee’s actions became a hot issue because she has played before in a Japanese drama. But A Man Called God is a Korean product and not an official Japanese promotion of the actor. Hyun-sung’s case is even more worrying: he never backed up his teammate and didn’t take an official position. What Japanese agencies seem to suggest is that even a mere association with South Korea’s claims is unfortunate. As long as K-entertainers keep an apolitical attitude, everything’s just fine and dandy.

And it was. A resembling situation took place 6-7 years ago. In 2005, Japan decided to establish “Takeshima Day” to commemorate 100 years since they occupied that territory. Needless to say, it broke into a huge diplomatic conflict. A month before though, BoA released a compilation album, Best of Soul, which will record 1 million sales in May, being hardly affected by the political fuss. In 2006, South Korea’s maritime survey around the Dokdo Islands has led to another scandal. Meanwhile, DBSK and Rain released their first Japanese album. In 2008, Japanese fans politely asked the public to respect Bae Yong-joon as an actor, since he’s not involved in any controversy thus far. By the time publications speculated the Hallyu wave was going to hit Japan, another artistic movement, in the form of Japanese literature, was going to hit South Korea. Cultural exchange, as long as it didn’t come near the political sphere, wasn’t compromised.

Keeping a low profile and tossing politics in the taboo corner is a convenient and inoffensive attitude. But aren’t these people entitled to express their political orientation? They are Korean after all, even presenting themselves as its spokespersons. Do they suddenly give up their support when it comes to conflicts?

There is no universal answer and problems always have more than one side. It’s understandable for the Japanese to take offence when they’re badmouthed in their own country. If idols want to succeed in Japan, it’s kosher to respect the country and refrain from any kind of offensive behavior, no matter what are their reasons to promote there. It’s a win-win situation which allows them to pursue both carriers: the Japanese and the Korean one. To sum it up: when in Japan, do as the Japanese do.

On the other hand, supporting their country is a part of their identity. They debut in Japan as artists and as long as their work isn’t affected, why shouldn’t they be outspoken? Another player in the game is by far more essential: the companies that allow cultural exchange (entertainment companies, broadcast channels etc.). Controlling the imported cultural products could be perceived as censorship, dangerously bordering with blackmail. It’s an exaggeration to restrict their right to activate in their medium due to their political views which, by the way, have generally little to do with their occupation. A Man Called God is not about the Liancourt Rocks and if anything, its cancellation takes the interchange between the two countries a few steps back.

Intercultural dialogue should promote an authentic bilateral contact, with the good and the bad. The difficulty in talking about idols’ right to speak up and how this is officially handled lies in the very nature of the entertainment industry, which directly operates with its consumers. The roles of idols, mediators and viewers can’t be accurately traced. Still, whether the public is right or wrong in judging them, it’s strictly a matter of communication between the idols as persons and their audience; another parties’ intervention sounds forceful and over the top.

What’s your take on this? Is ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ a politically correct policy in this case?

(Chosun Ilbo, The Korea Herald, Instiz, Football Korea, Asia Times, WSJ, Dramabeans, Yomiuri, France24, BBC, GLAM’s me2day)