Webtoons are often the unsung heroes behind Korea’s most popular TV dramas. In the past decade, they have served as source material for some of the best-known dramas of the past few years, including Misaeng, Bridal Mask, Cheese in the Trap, Save Me, What’s Wrong with Secretary Kim?, and the recently aired Itaewon Class.

In the past decade, there have been 26 webtoon adaptations on television; more than half of those adaptations have occurred in the past two years. Dramas that are currently airing that are inspired by webtoons include Memorist (based on the eponymous webtoon by Jae Hoo), Welcome or Meow: The Secret Boy (based on “Eowseowa” by Go A-Ra), and Rugal (based on the webtoon of the same name by Rilmae).

Webtoons, or webcomics, are an artform based in the more traditional comic or manhwa format which have been popularized in Korea. Typically, webtoons are broken down into chapters or episodes that play out a user’s screen through the endless scroll function. Panels are laid out vertically, such that users scroll down the screen to read. Endless scrolling, coupled with action that takes place across panels, results in an effect that feels like a motion picture. This sensation is purposeful, embedded in a culture where webtoons, dramas, films, and technology converge.

Rather than point to the single “origin” of a webtoon-based cultural product (i.e. the webtoon that inspires a drama adaptation), adaptations encourage viewers to consume more broadly. Using this framework, the adoption of webtoon content occurs at both the level of production as well as consumption, resulting in a transmedia storytelling culture in which stories are told across screens. Webtoons engage in this cycle by mobilizing photographic techniques and reflecting on their own identities and realities as web-based comics.

Easy accessibility is a key factor in the popularity of webtoons. During the early 2000s, webtoons surged in popularity as they were incorporated on portal sites like Naver and Daum, which continue to host webtoons for international audiences. Previously, readers had to purchase or borrow comics. Critics have conceived of webtoons having three generations. Currently, we are in the “third generation” of webtoons, marked by the advent of the smartphone and tablet. In this era, readers are able to access webtoons on their phones, from anywhere and at any time.

Webtoons are optimized for smartphones, from the prototypical webtoon with pictures and quotes on a vertical display to those with special effects such as sound and vibration. As webtoons have grown in popularity, portal sites have recognized their adaptability – Daum’s website even includes information about “2nd-phase projects for selected webtoons,” including “webtoon adaptations, character product development and penetration into the global market.” Clearly, webtoons are a source of potential revenue for content creators, as they can be mobilized across cultural forms including television, film, and musicals.

Built-in fanbases are an advantage to adapting a webtoon for the screen. Webtoon fans often follow dramas based on their favorite works from the casting stage to the show’s eventual airing. If you are involved in the K-drama community at all, you’ve likely seen side by side comparisons of a casted actor and the webtoon character they will play in an adaptation. Though seemingly trivial, these comparisons reveal the larger cultural web in which webtoons are only a mere thread; in order to make such judgments, audiences must already possess a working knowledge about actors and dramas. The opposite also occurs: those in the webtoon community discuss which webtoons they would like to see adapted and even create “fancastings.” In other words, knowledge about one cultural product informs audiences’ knowledge of another cultural product.

Webtoons attract large audiences in part because of their wide appeal. Webtoons represent diverse genres and themes, including thriller, historical fiction, and mystery. What is more, webtoons oftentimes tackle complex socio-cultural issues deeply embedded in Korean society. Take, for example, the class struggle that drives Itaewon Class or the critique of toxic beauty culture central to True Beauty. Though the webtoon format can be minimalist and compact, visually no larger than a smartphone screen, their stories are anything but. Producers add dramatics to the already rich, original messages and episodes.

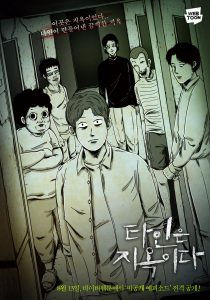

In order to tell complex stories, webtoons heavily on various visual cues. Webtoons are easily imaginable as movies or television dramas. Some webtoons employ distinct visual aesthetics, like the blue-grey color palette of Hell is Other People by Kim Yongki; the color choice instantly communicates a dark and suspenseful mood to readers. Other webtoons develop complex storylines through experiential scenes; instead of having a character merely explain the past, webtoon authors are able to write in scenes that allow readers to experience the past. “July Found By Chance,” adapted as Extraordinary You, masters the nonlinear narrative, which the artist visually cues with a distinctive sheen drawn over scenes belonging to a particular narrative world. The sheen looks like a photographic filter, turning the scenes a sparkly pink in their entirety.

These types of cues empower writers and producers to imagine settings, characters, and the dynamics of a scene when they go to adapt webtoons. Moreover, these cues are easily translatable onscreen because they mimic photographic effects like color grading, lighting, zooms, and lens flares. Here we see the cycle in which webtoons influence filmographic choices and film techniques influence webtoon creators.

Of course, webtoon adaptation is a fraught business. In adapting a webtoon, producers must satisfy both the fans of the original and those who haven’t read the original. Inevitably, there will be both similarities and differences between webtoons and their television adaptations. These continuities and contrasts with the “source text” are made by producers who are tasked with boiling down epic-length works into two hours of screen time.

Surprisingly and not always successfully, changes to an original story can appeal to audiences. For example, My ID is Gangnam Beauty followed generally the events of the webtoon closely, but highlighted side characters and their respective conflicts. The story in its simplest form is as follows: Mi Rae is bullied all of her life and decides to undergo extreme plastic surgery on her face before she begins university, but the appearance of her former classmate threatens to jeopardize her new identity. In the drama version, Mi Rae’s family plays a much larger role and with success. The show’s writers and producers tell the story of extreme plastic surgery from the parents’ point of view, a fresh point of view that appeals to a wider drama audience. Mi Rae’s parents struggle as they watch their child feel pressured into plastic surgery despite their love. In a touching scene, Mi Rae mends her relationship with her father, who at first disapproves of her surgery.

In contrast, Orange Marmalade is an often-referenced example of a “poor” adaptation by fans. The webtoon is set in a universe where vampires live among humans and features the love story between a vampire who despises humans and a human who (it is ultimately revealed in a dramatic twist that the drama adaptation neglects) despises vampires. The drama maintained these characters but set up their universe in a different way, pushing the story back into the Joseon era and giving the characters new identities. Such drastic changes reflect popular dramatic tropes, including the use of dramatic backstories of star-crossed lovers from another time. Once stories enter into the adaptation cycle, changes are necessary to appeal to different audiences.

Television writers and producers go to varying lengths to reference a story’s webcomic origins. Itaewon Class featured an homage to the webtoon genre in the form of a comic-like introduction with paint splatters and drawn versions of the main characters. Other adaptations require more thorough reference to webtoons because the original story explicitly engages with the webcomic form. For example, Extraordinary You features main characters who gradually discover that they are actually characters within a comic. W, though not based on a webtoon, centers on the clash between two worlds – the real world and an alternate universe inside a webtoon. This metatextual conversation between comics and the screen is infinite in possibility because it can occur on these various registers, from the webtoon’s original story to the television’s introduction slate.

Though it might be instinctual to write off a webtoon adaptation as merely “good” or “bad,” it is important to keep in mind that even “bad” adaptations point to a complex media culture that situates viewers in an ever-growing metatext. Webtoon-based products, like drama adaptations, are increasingly important because they reveal the ways in which media overlap. Moreover, they empower audiences to perceive the flow of stories and seek information from multiple sources.

(Daum Webtoon, Naver Webtoon, The Korea Herald. Images via KBS, The Korea Herald, Daum Webtoon, Naver Webtoon, Line Webtoon, and Netflix)

What are your favorite webtoons and/or webtoon adaptations? How have adaptations enriched your understanding of the original story?

Also, what webtoons would you like to see in drama or film form? Share them with us in the comments!