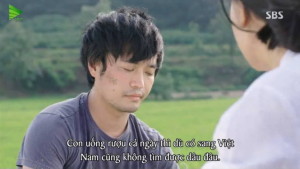

Do any of our drama fan readers recognize this scene?

It’s from SBS‘s drama “Modern Farmer“, where the mother is lecturing her drunken son about getting married. Written in the photo is the Vietnamese subtitle that says:

If you keep drinking everyday like that, even if you go to Vietnam you will not find a bride.

The scene was considered an offense toward Vietnamese women and angered Vietnamese online communities enough for the photo to be spread like wildfire over Facebook. It got to the point that SBS has run into some serious troubles with the Korean Consul General in Vietnam for its lack of consideration. The station has stepped down and apologized, and Modern Farmer continued to air normally, but the story may run deeper than that.

First of all, let’s talk a little about the background of Vietnamese brides in South Korea.

“Vietnamese bride” has become a significant phenomenon in South Korea starting from the early 2000s. Each year, hundreds of poor Southeast Asian and Chinese women, as a way to finance their life and family, get married with middle-aged or older Korean men. The largest, hence the representative population of these foreign brides, comes from Vietnam. These hybrid families are very ceremoniously and officially named by the Korean government as the “multicultural” families — “다문화가족”. (Note: you will never see Korean people calling a family consisting of a Westerner and a Korean being called that. The title is reserved for this group of Asian women only.)

There are loads of things to ponder over this phenomenon. Firstly, why do old Korean ajusshis in rural areas look for a foreign bride? With the economic development and slightly improved gender equality, many young Korean women no long wish to stay in the villages, no longer wish to get married early or get married at all and the idea of taking care of a household and obeying a husband is growing more unappealing. Therefore, many Korean poor, old male farmers are struggling to find enough wives who are willing to fulfill a traditional role. Korea as a country is struggling to find enough labor. The solution is to “import” women from poorer neighboring countries.

Secondly, how do the future brides meet their husbands? There are so-called marriage matchmaking agencies, which have become a seriously profitable business in Korea. Here is the process from a Korean mother’s perspective: you are a mother of a son who is a farmer in some poor area in southern Korea and about fifty years old and unmarried. You go to a matchmaking company and ask for some candidates. You and your son shall later go to Vietnam, or wherever the agency has connection with in Indonesia or China, meet those girls and choose one.

Secondly, how do the future brides meet their husbands? There are so-called marriage matchmaking agencies, which have become a seriously profitable business in Korea. Here is the process from a Korean mother’s perspective: you are a mother of a son who is a farmer in some poor area in southern Korea and about fifty years old and unmarried. You go to a matchmaking company and ask for some candidates. You and your son shall later go to Vietnam, or wherever the agency has connection with in Indonesia or China, meet those girls and choose one.

You pay the agency and the woman. She shall go to Korea later, gain a special “multicultural family” visa, and hopefully won’t run away. This is not always the case — I am over-generalizing a lot here — but it is the general process.

Lastly, how do these foreign woman cope with a sometimes racist and used-to-be homogeneous Korea? The South Korean government offers a lot of “education” programs for these women so that they can fulfill their role as a good wife for South Korean men. They learn to cook, to make kimchi, and to speak Korean. Yes, you read it right, Korean language. Many of these young ladies do not even speak a word of Korean when they get married with their Korean husbands. Do the husbands need to be educated about their wives’ home country? Let’s leave it to the man’s own good will.

With these very basic facts about one of the most problematic issues in modern Korean society, let’s talk about how the Korean dramas and films deal with over one million members of multicultural families in this 50-million population. Overall, as they do with many other aspects of Korean society, K-dramas and films tend to deliver a much more watered down but very romanticized image of these multi-racial marriages.

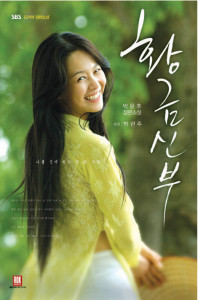

Some meaningful mentioning of the foreign brides would be again from SBS in their 2005 short drama Hanoi Bride featuring Lee Dong-wook and Kim Ok-bin, and their 2007 award-winning Golden Bride, featuring Heechul and Lee Young-ah. Both talk about middle-aged Korean men getting married with Vietnamese women through an “international” matchmaking agency, though in an extremely romanticized and unrealistic fashion.

Some meaningful mentioning of the foreign brides would be again from SBS in their 2005 short drama Hanoi Bride featuring Lee Dong-wook and Kim Ok-bin, and their 2007 award-winning Golden Bride, featuring Heechul and Lee Young-ah. Both talk about middle-aged Korean men getting married with Vietnamese women through an “international” matchmaking agency, though in an extremely romanticized and unrealistic fashion.

The character of Kim Ok-bin is chosen to marry Lee Dong-wook’s brother through a matchmaking service, but eventually finds her way back to her “true love”, the much more handsome, well-educated, richer younger brother. Similarly, Lee Young-ah finds acceptance and support from her husband’s family very quickly and enjoys a loving relationship with her husband. The two films seem to deliver a message to both their Korean and Southeast Asian audience that Vietnamese wives are acceptable, will be accepted and everything will have a happy ending. Except both the lead female characters in these dramas are not even purely Vietnamese, they are half-Vietnamese, half-Korean. They speak fluent Korean from the very beginning, which is never the case as I have mentioned earlier. Besides, to be honest, Ok-bin and Young-ah’s Vietnamese sounds horrible.

Some other less famous examples that discuss either briefly or extensively these international marriages are KBS‘s 2010 drama Hometown Over the Hill and SBS’s 2008 reality show Meet the In-Laws. Hometown Over the Hill is a sweet portrayal of everyday life in rural areas of Korea, and KBS at least uses an actual Vietnamese woman to play the role of the Vietnamese wife here. Meanwhile, Meet the In-laws brings the audience to visit the family and hometown of the foreign wives from diverse nationalities. Both of these examples suggest a possible satisfactory outcome for international marriages, including those “multicultural families”.

Even though K-dramas and films portray multi-racial marriage in Korea quite positively, a much more comprehensive and elaborate study from Professor Epstein at the University of Sydney observes that:

These shows are inculcating a hierarchical sense of South Korea’s relationship with an Asian hinterland, and simultaneously promoting a radical shift in Korea’s gendering of the “foreign” from male to female.

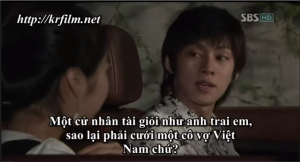

It is quite a spot-on conclusion. One noticeable thing is that in Golden Bride, Heechul does have a line that sounds very familiar with the troublesome script of Modern Farmer, in which he says, “Why does a talented bachelor-degree holder like my brother have to get married with a Vietnamese bride”? As you see below, there was even a Vietnamese subtitle for the scene, but no one noticed it and made a fuss in 2007. K-dramas and K-films can romanticize and beautify the prospect of multicultural families for all they want, but accidental slips like this line of Heechul seem to tell us that the actual attitude towards Vietnamese women has not changed much over seven years — they still don’t deserve a “good” Korean man, their “eligibility” status in marriage should still be placed at a “lower” tier.

It is quite a spot-on conclusion. One noticeable thing is that in Golden Bride, Heechul does have a line that sounds very familiar with the troublesome script of Modern Farmer, in which he says, “Why does a talented bachelor-degree holder like my brother have to get married with a Vietnamese bride”? As you see below, there was even a Vietnamese subtitle for the scene, but no one noticed it and made a fuss in 2007. K-dramas and K-films can romanticize and beautify the prospect of multicultural families for all they want, but accidental slips like this line of Heechul seem to tell us that the actual attitude towards Vietnamese women has not changed much over seven years — they still don’t deserve a “good” Korean man, their “eligibility” status in marriage should still be placed at a “lower” tier.

It is understandable that the children of these multicultural families suffer from discrimination. The reason why Psy‘s photo is at the top of this article is because of the little kid dancing beside him — “Little Psy” Hwang Min-woo. Min-woo, whose mother is Vietnamese, has received extremely malicious attacks from Korean netizens after he had appeared in Gangnam Style and became famous. The family eventually resorted to legal actions to stop the bully, but the case itself was only one ugly and horrendous incident out of so many where children from multi-racial families are not accepted in Korea.

Min-woo’s story shows us how biased and hostile a part of the Korean population can still be toward people from a different nationality, despite all the rose-tinted drama portrayals and propaganda efforts from the government with the help of the media. It is not so much about these entertainment products that I am criticizing, but the negative thinking of many Koreans that runs deep and firm despite all the efforts to make them think otherwise about “multicultural families”. Even though the foreign brides may choose to come to Korea with a price tag on themselves, they deserve respect and their children definitely deserve acceptance.

(Sources: Tuoitre News [1] [2], Talk Vietnam, The Economist, The Independent, Washington Post, Aljazeera, The Diplomat, The University of Sydney. Images via YG Entertainment, SBS, Youtube [1], [2], [3])