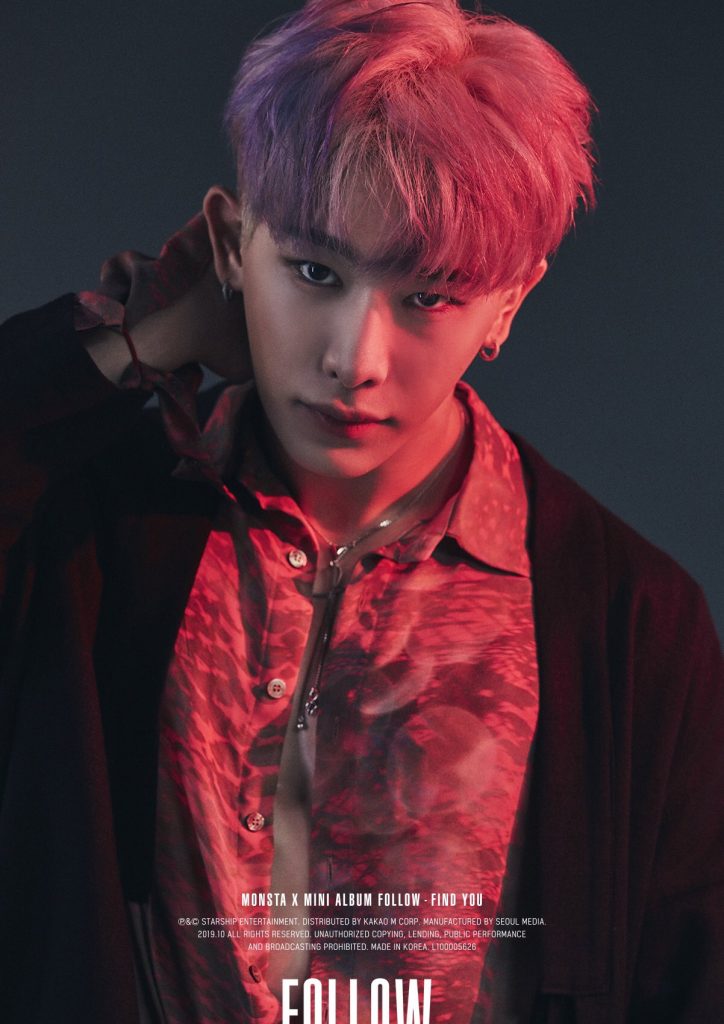

From Seungri and the ensuing YG debacle to members leaving their groups—the most recent and shocking being Wonho‘s departure from Monsta X—and more, this year has been a wild ride. For these reasons, some fans have been proclaiming 2019 as the worst year of K-pop.

This month, we ask our writers: It’s not the first time K-pop has had a tumultuous year—what makes 2019 seem to stand out as a particularly bad year? What do the various events reveal about issues like the idol-fan relationship and the public’s expectations of idols? How is the newer generation of idols responding to and being treated differently (or not) when it comes to allegations, as compared to their seniors?

Qing: I’ve seen debates over whether 2019 replaces 2014 as the worst year for K-pop. I think they’re difficult in different ways, and therefore hard to compare in terms of which is worse. And yet it’s not possible to label both years simply as “the worst”, for the incidents they brought watershed moments in the larger socio-political context.

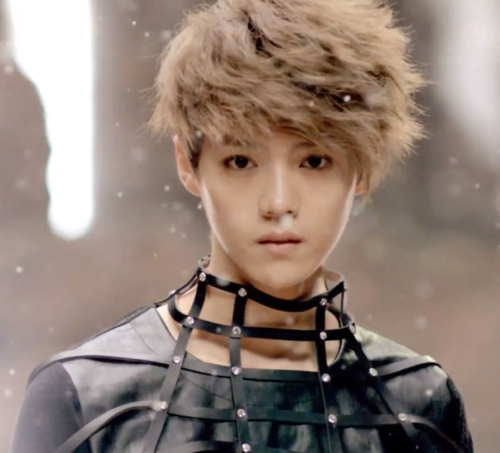

2014 had three cruel tragedies and shock departures of idols from successful, popular groups. The shadow of the Sewol ferry incident loomed over the K-pop scene, and the resultant outburst of resentment and distrust at the Park Geun-hye administration saw microcosmic parallels in idols lashing out against their companies’ oppressive slave contracts (Exo‘s Kris and Luhan, and all of B.A.P).

Likewise, the Burning Sun events arrive at the heels of the #MeToo moment taking off in Korea. What used to be swept under the carpet has come spilling out into the open. Unlike before, public figures (including those in the K-pop industry) are increasingly being held accountable for their misdeeds and choices. Whereas the standard operating procedure used to be a vague apology and a “period of reflection”, more idols are now approaching allegations with frank statements and decisions to leave their groups or even the industry. The incidents are also a sobering reminder for fans that there are always sides to our idols we do not see.

Yet, as we see in Wonho’s case, it’s not all positive. Targeted attacks become confused with justice-defending whistle-blowing and a sensational approach to allegations causes past actions to be viewed without context. There’s a fundamental difference between a person motivated by desperation and powerlessness, and those who, like Yang Hyun-suk and Seungri, make choices from powerful, privileged positions.

Karen: As Qing mentioned, 2014 was a pretty bad time for the industry and the country as a whole, but somehow 2019 feels even more disturbing beyond the recentness of the events. Whether it is Girls’ Day’s Minah being threatened online following Sulli‘s passing, up till the most recent controversy surrounding Monsta X‘s members, 2019 has made me realise the stakes we have to pay for freedom of speech with the internet.

If the K-pop industry cannot wait to take advantage of the connectivity offered by online media outlets like V Live, Twitter, YouTube, Instagram, and more, society certainly is not prepared to deal with the ugly side of internet anonymity and generally free-for-all online platforms. Even as celebrities are displayed for the consumption of consumers, they are also being seen as dartboards for haters. Between them and these haters, there is nothing to protect these idols from the abuse or accusations other than the glass screens of their phones.

2014 might have spotlighted idols in contention with their companies but at least there are faces to put on the stakeholders involved. With the internet, anonymity makes everyone kings and queens, and it is hard to contend with a blurry mass of usernames and social media handles. Unlike 2014 that revealed the failure of organisations, 2019 seems to be reflecting a greater society’s inability to manage issues delicately, choosing sensationalism and vindictiveness instead.

Zea: I became a K-Pop fan in earnest in 2014 and I can remember all the tragedies vividly: the untimely passing of Ladies Code members, the lawsuits upon lawsuits against companies, the departures and indefinite hiatuses of numerous members. Yet 2019 feels worse. I think this is because there was still an underlying hope that things would be okay in the end; the idols leaving must have had a good reason to do so and thrive without their company, that scandals would pass over and groups would promote again, that we would work through our grief and emerge stronger.

I think this hope is somewhat diminished in 2019 because there doesn’t seem to be a lot of hope. Everything has turned into the worst possible version of what it could be. Scandals that we hoped would blow over led to members leaving and fragmenting groups, or, worse, being exposed as terrible human beings who we had been supporting all these years. There doesn’t seem to be any chance for any redemption; it seems like a long shot that members will be able to come back and promote again, despite fan’s support. It seems like the gentle shall inherit grief and online hate, while the bad don’t get so much as a rap on the knuckles. This hopelessness, combined with the tense political climate around the world, makes 2019 seem like the worst year in K-Pop.

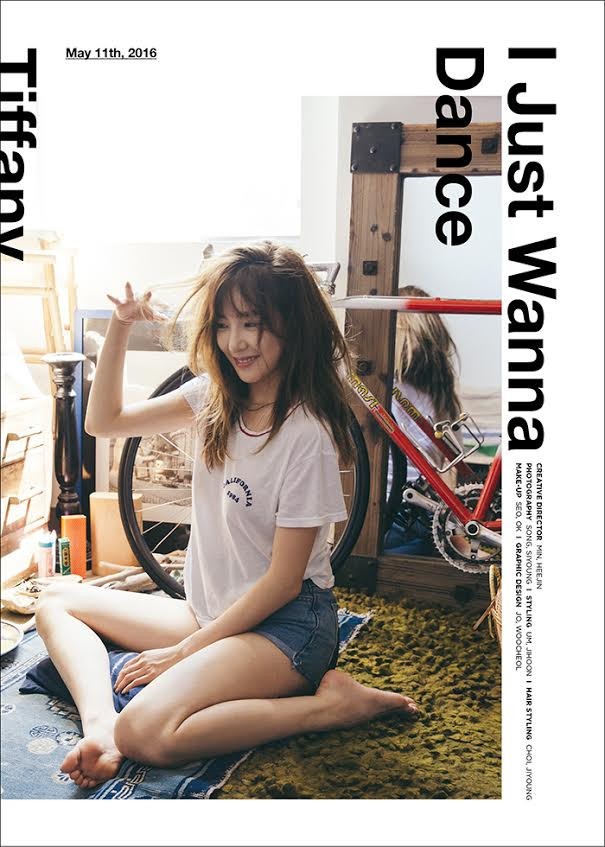

Qian: I do agree that socio-political watershed incidents seem to have an effect on the way we view each year. I had a similar discussion in 2016 about how at the rate it was going, it was going to give 2014 a run for its money. From Tzuyu and Tiffany’s respectively overblown flag incidents, KARA and 2NE1’s disintegration, Nam Tae-hyun leaving Winner, Hyunseung leaving B2ST as well as Yoochun’s multiple sexual assault allegations, there’s a lot to unpack here. And we haven’t even got to the matter of Park Geun-hye’s scandal that would eventually lead to her imprisonment in the following year.

Yet in retrospect, 2016 wasn’t that bad. Certainly not bad enough to be kept in the running alongside 2014 and 2019. Maybe it’s the fact that those groups eventually bounced back one way or another. Personally, my theory is that with Park Geun-hye’s issue resolved in a satisfying manner, 2016 was cast in a better light after. Granted, the idea is naively simple, and correlation isn’t causation, but assuming that K-pop fans in general are aware of the large-scale events happening within Korea, it’s not out of the question that these events and how they were handled would affect our perception of K-pop as well.

That being said, it does seem that the public has adopted a more critical outlook towards celebrities and scumbags, in general, this year. With how the Burning Sun controversy had placed the character of some of our favorite idols into serious question, and the #metoo movement, it’s not hard to see why. With regards to incidents that made us question the character of various celebrities, 2014 barely skimmed the surface — like Karen mentioned, it focused on idols’ relationships with their companies. Maybe that is why 2019 stands out as a particularly bad year.

Janine: I used to say I got into K-pop to escape the news and I wish I had a time machine to visit Past Janine and laugh in her face. I will echo everyone who raised the point that there is a shift in the socio-political/moral landscape. Revelations about celebrities across the globe are prompting fans to be a lot more critical about what (and who) we buy into.

Scandals of previous years have not always changed my view of the morality of the people involved. I expect entertainment companies to prioritise their bottom line over idols’ wellbeing. I expect idols to date, to suffer from mental illnesses, and even to leave the idol life. I expect them to have different political views and to hold opinions with which I disagree. I expect idols to make mistakes.

I did not expect that this year, a large group of idols would be involved in the kind of crimes that keep me, and many other women, afraid for our lives, autonomy, and dignity. The Burning Sun scandal was not so much opening a can of worms as discovering half a worm in your salad at your favourite restaurant and them saying, “Oh yes, most of the food is worm-based” when you complain.

I can pretend cynicism about these events but I won’t. I don’t listen to music or watch MVs trying to spot the sexual predator and it’s surreal trying to navigate the K-pop after all of this. Especially since Burning Sun has not yielded many legal consequences nor has the #MeToo movement exposed every perpetrator. I remember something my best friend said, “What if it’s all of them, how will we know?” That is what made 2019 so difficult for me as a fan: all the things I don’t know.

Rimi: Regarding the things we don’t know, I think that with the way idols have taken to social media, much more of idols’ lives are on display more than ever before. As Sulli’s example shows, this isn’t necessarily a good thing. However, the Burning Sun controversy was confined to members of second-generation boy groups, and I do think there’s much less known about them than members of current third-generation boy groups — simply because social media wasn’t quite as big before.

I say all of the above with caution since I got into Kpop in 2017. As a third-generation boy group fan, I can’t help but wonder if I’m looking for ways to reassure myself that my favorite idols are better than that. For instance, Wonho and B.I’s alleged actions aren’t disturbing in the way that Seungri and his friends’ actions were. However, it may just be that the third-generation of boy groups are (mostly) younger and therefore not as far gone as Seungri and friends.

Through exceptional marketing, the K-pop industry carefully places a veil between the idol and the fan. 2019 has been instrumental in helping lift that veil, but now I’m left doubting everybody, and thanks to Burning Sun, especially male idols.

Semi: For me, 2019 stands out because of its unprecedented levels of instability.

The Burning Sun scandal marked a shocking change: this was no petty rumour about romantic relationships, nor was it poor behaviour that could be brushed under the carpet after an apology and a period of reflection. For several celebrities to be so deeply involved in numerous unforgivable crimes was highly upsetting. Long-standing household names had their dirtiest secrets exposed to the world and this left behind an uneasy atmosphere: who else was involved? Who else had been hiding behind fame whilst breaking the law or abusing others? Now that we had seen how awful things could be, we became suspicious and on edge.

This unstable state, in which it seemed that any idol who we admired might turn out to be a terrible person, has not been lightly dealt with by entertainment companies. Subsequent scandals, which previously would have been treated with more of a slap on the wrist, have therefore resulted in more drastic action, such as B.I and Wonho’s departure from their respective groups.

A side point: I have never been a fan of the survival shows that have become so popular these days, so perhaps I’m going a little far, but the survival show itself seems to reflect the instability of K-pop idols’ position and success. Contestants being easily discarded has become a form of entertainment. With temporary groups coming and going, and group members such as Stray Kids‘ Woojin disappearing seemingly spontaneously, there doesn’t seem to be much stability in K-pop these days. Having debuted is no longer a guarantee of staying on the stage.

Gina: As most have voiced, 2019 is the year of extreme instability and corruption that leaves us questioning the raw “reality” behind the fabricated landscape of K-pop. This virus of instability has spread towards multiple areas, from politics to cultural society — we got Jung Joonyoung, Choi Jonghoon, and Kwon Hyukjun being demanded to serve an ‘x’ amount of years while Seungri remains free, and we also saw a reboot in the power behind Instagram. Over common sense, that is.

For instance, the blazing support behind Goo Hyesun’s emotional, ungrounded Instagram posts were rather shocking — when later, forensic investigations revealed the depth of her lies. Announcing cheaters online has become a trend after Jang Jaein paved the way, to mixed results. Jungkook and Hash Swan endured plenty of virtual wrath for a topic that should not even be a public discussion. And, as is the freshest in our minds, Han Seohee and Jung Daeun teamed up to oust Wonho from society… while dragging Shownu in, as well. Instagram is now a medium that all agencies will now have to pore over. Anything can be spoken and believed since nobody likes to wait anymore. The public has nurtured a new entitlement over public figures, perhaps in response to how much is accessible about them. Privacy and truth have been thrown out the window, replaced with the demand to “know” (read: the itching notion that celebrities can’t be less than perfect, to hell with their career).

Ultimately, we see a growing parallel in leverage — money and media can both do wonders for celebrities, for better or worse. The outcomes behind these conflicts remain complex and confusing, escaping the simple confinements of morality and truth. Altogether, it comes down to how the industry, law, and netizens deal with the humanity behind celebrities.

Zea: To echo Rimi and Gina, the omnipresence of social media adds to the “worseness” of K-Pop this year. It has become a powerful tool for celebrities to accuse and expose as well as for fans and anti-fans to dissect, discuss, degrade, and dismiss.

There isn’t an “off” mode. Whenever anything happens, fans immediately take to social media to either crusade for their idols, create drama via edgy, misinformed takes for the clout of it, or just continuously retweet or reblog posts about it. This constant array of information and updates, alongside news about the ever-worsening world, is inescapable, overwhelming, and anxiety-inducing. This, I think that has helped make 2019 arguably the worst year in K-Pop.

If you found this to be a meaningful read, you may also like these articles:

- Wonho Leaves Monsta X: Impact, International Fandoms & What It Means To Be an Idol

- Roundtable: It All Started With Seungri*

- A Fan’s Dilemma: On Molka and Sexual Violence*

- Open World Entertainment and The Ugly Side of K-pop*

*Please note that these articles discuss instances of sexual abuse and harassment.

If you or anyone you know is experiencing distress, a list of helpline numbers from around the world can be found here: www.iasp.info/resources/Crisis_Centres/

(Images via Starship Entertainment, SM Entertainment, Big Hit Entertainment, Polaris Entertainment, YG Entertainment, JYP Entertainment, SBS Entertainment)