A time of upheaval for women has finally come for South Korea, a country typically thought of as a male-dominated society. In the past week, South Korea’s President Moon Jae-in has expressed his support of the #MeToo movement. The media continue to be abuzz regarding the allegations of sexual misconduct against prominent figures in the country. Even though the movement has reached South Korea belatedly, it still remains a force to be reckoned with. These female voices are overturning society by speaking out on a topic that has long been considered taboo.

A time of upheaval for women has finally come for South Korea, a country typically thought of as a male-dominated society. In the past week, South Korea’s President Moon Jae-in has expressed his support of the #MeToo movement. The media continue to be abuzz regarding the allegations of sexual misconduct against prominent figures in the country. Even though the movement has reached South Korea belatedly, it still remains a force to be reckoned with. These female voices are overturning society by speaking out on a topic that has long been considered taboo.

In 2006, Tarana Burke founded the #MeToo Movement to help survivors of sexual violence, building a supportive community for these individuals. Those pushing the movement ahead are determined to disrupt any system that allows sexual violence to persist. In October 2017, the #MeToo Movement was brought to media attention in the accusations against U.S. film producer Harvey Weinstein of sexual misconduct.

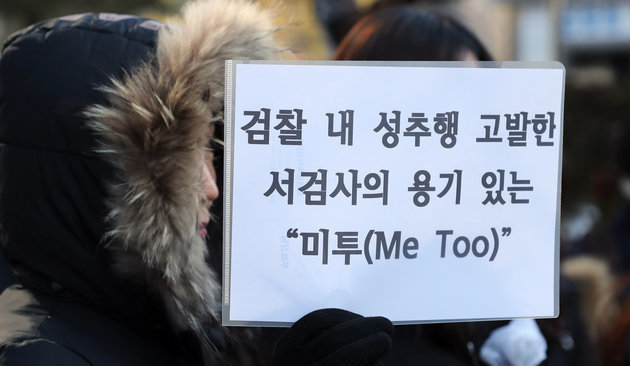

When South Korean female prosecutor, Seo Ji-hyeon, spoke publicly of being groped by Ahn Tae-geun, South Korea’s former Ministry of Justice prosecutor, she inspired many more women to speak out of their own experiences of being sexually harassed or assaulted. The accused holds a position in the government justice system, and Seo’s accusations raised hopes that appropriate action would finally be taken. Ahn has also since agreed to cooperate with prosecutors investigating Seo’s claims.

Women from numerous other sectors are speaking out as well, including women in powerful positions facing the same harassment from their male colleagues. Lee Jae-jeong, assemblywoman for the Democratic Party in South Korea, disclosed on Facebook on Jan 30:

To stand by Prosecutor Seo Ji-hyeon, I wrote and deleted this post a couple of times, still showing my hesitation. This is what I wasn’t able to do when I was a lawyer. This is what I hesitate to do even though I am an assemblywoman.

Lee included the hastags #MeToo and #WithYou in her post. She later discussed details of her sexual assault on an interview she gave on Kim Hyeon-jeong’s News Show.

Students and alumni from Seoul-based universities are also coming forward with stories of sexual misconduct under authoritative figures. Posts recounting these experiences are beginning to appear on online communities. Yeon Hak-kang, a graduate student at Hanyang University, expressed on Facebook the distress she felt after the persistent sexual harassment from a male lecturer, as well as from her male academic advisor.

Students and alumni from Seoul-based universities are also coming forward with stories of sexual misconduct under authoritative figures. Posts recounting these experiences are beginning to appear on online communities. Yeon Hak-kang, a graduate student at Hanyang University, expressed on Facebook the distress she felt after the persistent sexual harassment from a male lecturer, as well as from her male academic advisor.

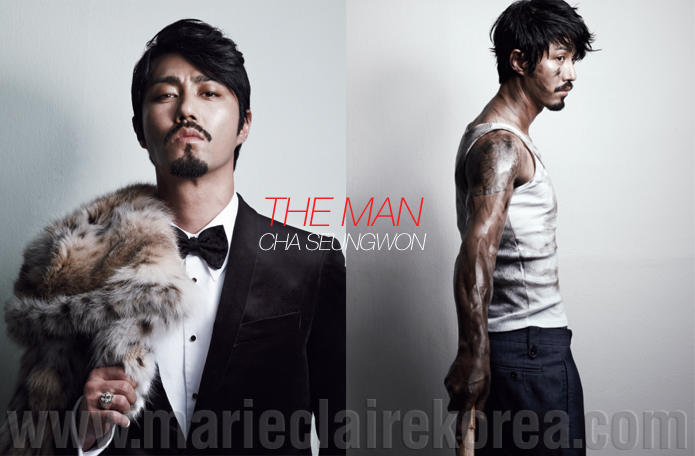

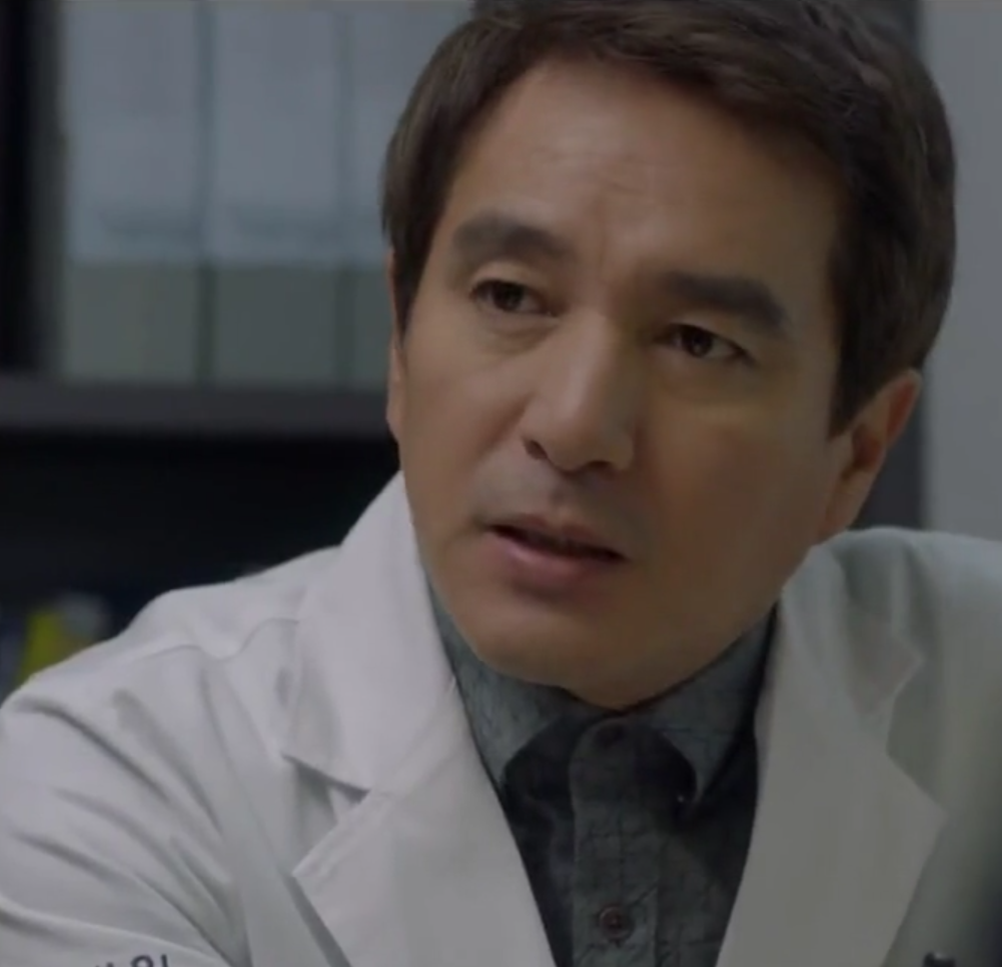

Perhaps the most sensational allegations the media have focused on are those directed at individuals in the arts and entertainment sector. Actress Choi Yul accused Cho Jae-hyun of sexually abusing her on her Instagram account. Cho, who is currently starring in tvN drama “Cross,” issued a statement of apology for his wrongdoings. Cho’s entertainment agency has since parted ways with him. Actor and university professor Cho Min-ki has also stepped down from his teaching position and left his role in a new drama series after facing allegations of sexual misconduct. Veteran actors Jo Jae-hyun and Yun Ho-jin have cancelled upcoming activities after admitting to sexually harassing women in the past. Oh Dal-soo also reversed his initial defense denying the accusations he harassed several women in the 1990s during his time in Yeonhee Street Theatre Trope. He has since publicly apologised for his wrongdoings, though admitting he can no longer remember clearly who the victims were.

In the past, these incidents of sexual misconduct would have easily been swept under the carpet, or never even been made known to the public. The tolerance for sex offences in the South Korean entertainment industry was considered to be relatively high, with victims afraid to speak out. Victims often fear the repercussions: victim-blaming, or simply the ineffectiveness of support structures to punish the perpetrators. In turn, they are more likely to be penalised for whistle-blowing.

An example of victims being betrayed by society would be the backlash faced by rapper Iron’s ex-girlfriend who had voiced out about domestic abuse. After hints of her identity was let slip in an interview of Iron with Sports Korea, fans had flocked to her Instagram. The entire incident has been termed by her legal representation as a “social media witch hunt.”

An example of victims being betrayed by society would be the backlash faced by rapper Iron’s ex-girlfriend who had voiced out about domestic abuse. After hints of her identity was let slip in an interview of Iron with Sports Korea, fans had flocked to her Instagram. The entire incident has been termed by her legal representation as a “social media witch hunt.”

Seoulbeats has discussed the difficulties to secure a conviction even in rape charges that do go to trial in a previous article. What is considered to be sexual violation in South Korea is very specific and limited, with the system allowing repeat offenders to rarely face consequences. #MeToo is throwing a wrench right into the core of a society that disadvantages women.

At present, the fear of speaking out is slowly dissipating. Blind, a chat app, allows individuals to anonymously speak out about their misbehaving bosses and co-workers. They have added a section dedicated to #MeToo stories. In the short 24 hours after the launch of the #MeToo platform on Blind, more than 500 posts flooded the system. The app was intermittently unavailable due to the heavy user traffic, reflecting the pressing need for these women to be heard.

With President Moon Jae-in backing the movement, a shift is almost a certainty. He voices out:

We should take this opportunity, however embarrassing and painful, to reveal the reality and find a fundamental solution. We cannot solve this through laws alone and need to change our culture and attitudes.

The momentum of #MeToo is pushing very strongly for a moment of revolution in terms of the society’s perception of gender issues. The development and the attention given to the entire movement needs a shift in not only addressing the issues of female oppression (tied to sexual harassment) only after it occurs, but also in giving a voice to women to shape societal perceptions of themselves. It is a resistance without the fear of having to face the terror of “witch hunts” and discrimination.

Even as more names are being thrown out in the growing number of allegations going public, it seems more and more unlikely that the public will be satisfied with any patronising statements. Individual statements are necessary, but what remains more vital is dishing out the appropriate degrees of punishment to offenders. Dealing with the aftermath of such accusations is important in this particular moment, driven by the force of the #MeToo Movement, but the future should not be one that remains stagnated on present gender perceptions. This is no longer a situation that will be easily dismissed with some words of apology with regards to past actions. Neither will these acts be swept away easily with inaction and mere time.

Sexual misconduct is a problem that should be addressed, even if it might require an uncomfortable rewriting of values that have long been held dear. Influential figures are stepping down from positions of power; they are admitting their wrongdoings and changing the way the public has seen them for a good many years. There is possibly no argument that can be put forth to resist such a considerably radical shift in perceptions and in society’s structures. Thinking of the women in South Korean society — mothers, wives, daughters — one should be more than glad to be swept away by the tide of #MeToo, even if it means rebuilding the very pillars that have been founded on patriarchal values.

(Asia One, The Diplomat, Huffington Post, The New York Times, Reuters, UPI, The Washington Post, Yonhap News Agency, YouTube. Images via Hankyoreh, Huffington Post, MeToo Movement, The Fact, tvN)