The first half of 2019 have seen Red Velvet flex their musical muscles to varying degrees of reception. Being one of a few SM acts in which founder and SM’s largest shareholder Lee Sooman (LSM) is still largely involved, Red Velvet’s artistry hitherto has not leaned far from the SM Sound which LSM has long envisioned: a mix between older sounds of late 20th century American pop and electronic-based futuristic sounds. While on paper it sounds like just any other K-pop act out there in the wild, wild music jungle, in practice Red Velvet are better equipped than most with the amount of ammunition they have in their arsenal.

I am looking at 2019 Red Velvet as I am looking at the trajectories of not only their catalogue, but also of LSM’s history. Like many youths under the regime of President Park Chunghee, LSM found himself gravitating towards the rebellious noise of heavy metal during his college years as an engineering student in Seoul and moonlighted as an underground DJ. Seeing no future in music, LSM then spent half of the 80s in the West Coast as a graduate student. Again, he was distracted, but this time it was not because of military dictatorship. The fledgling MTV with Thriller-era Michael Jackson at its helm was there.

Early ‘80s Jackson was a Jackson who was reinventing himself out of his Jackson 5 mold and going as far to distancing himself from the Motown Sound. The 80s also saw the Midwest pioneer house music in Chicago and techno in Detroit, which was also part of the trend of parting from Motown. The decade marked the diversification of hip hop stateside, bringing, again, Detroit and Chicago to prominence with their new take of hip hop meets house, while New York City maintained the old school style. These three movements lent a heavy hand to the formation of what would be American pop music in the 90s and early 2000s.

The rest of LSM’s infatuation with Jackson-fronted MTV is history as we know it. The LSM-coined term “cultural technology” dictates that new Korean pop stars shall tread on Jackson’s legacy and flaunt a flair of camp. Of the former, it manifests in K-pop a la SM: vocal prowess, catchy music, and visually grand music videos. Of the latter, it is an eclectic cocktail of avant-gardism a la John Cage, transnational influences that one can chew without taking years of music education, and a huge debt to the Black American legacy in American music.

In principio

Officially, LSM resigned from SM’s board of directors in 2010. His having a hand in Red Velvet’s affair was conducted through Like Planning, a music consulting company he owned and whose fee was part of a suspected embezzlement and SM’s restructuring in mid-2019. Nevertheless, on an episode of Happy Together, Joy mentioned that LSM told her he took part in the production for “Red Flavor,” and yet their managers did not disclose the information until the group asked them about it. The girls also had a group chat with LSM in it. A man with an eye for detail, LSM gave not only encouragement but also inputs even for their choreography and styling.

It is noted that what I would later understand as “SM future sound” would have to wait until the latter leg of their second generation of idols, largely carried by Shinee and f(x). Along with SM’s then-flagship group SNSD, Shinee carried one of the characteristics of SM’s future sound — the disjointed song structure — as early as 2010’s hit “Lucifer.” Along with SNSD’s “Oh!,” “Lucifer” helped popularize the disjointed structure trend that currently over-saturates K-pop.

Future sound aside, LSM’s infatuation with MTV era American pop sound remained such that SNSD was made to work with Teddy Riley, Jackson’s former producer and one of the pioneers of new jack swing, for the underwhelmingly dated-sounding “The Boys,” which was neither recalling any Jackson vibe nor being futuristic at all. This also marked a failed foray into the US market that LSM had coveted since a modest success of neighbor and competitor Park Jinyoung, himself an admirer of Jackson and self-titled Man from the Future. The rivalry between the two Jackson fans was not put out of sight. In The Monthly Joong Ang article collected in the journal Korea Focus in 2012, journalist Baek Seungah reported that Riley called Park-produced Wonder Girls “a flop,” for going after the retro, Motown-esque sound.

Shinee’s sister group f(x) carried the torch for the future sound next by bringing electropop and synth-based arrangement to the front, expanding what SNSD had previously touched upon with their Japanese discography such as “Galaxy Supernova” and “Karma Butterfly.” f(x)’s grittier, harder beat hitter exploration in Red Light the following year was released only a month apart from the debut of SM’s then-youngest group, Red Velvet, who in a few years going forward would show what it was like if a weightier f(x) sound met a more mature SNSD sound.

Audio, video, disco*

Less than a year after their debut, the now five-membered Red Velvet made a literal tribute to Jackson in “Dumb Dumb,” somewhat a sister song to Shinee’s Jackson-esque “Married to the Music,” both composed by LDN Noise. Irene and Joy took part in rapping titles of Jackson’s hits, the girls belted high in a style reminiscent of “Beat It,” they wore surgical masks for one of the photoshoots just like Jackson used to do, and some of Jackson’s moves were memorialized in the choreography. Had SM added guitar tracks akin to what Eddie van Halen and Steve Lukather did for “Beat It,” “Dumb Dumb” would have been a Michael Jackson-Jessie J combo. Thankfully, the multi-layered vocal tracks made “Dumb Dumb” as Red Velvet as Red Velvet could be.

While “Dumb Dumb” is full of high energy and high belting and lies high on bpm, it is not the noisiest Red Velvet record. Let me clarify first that here I do not mean noise in a pejorative condescension, where you would label a song you fail to understand as noise. I am understanding this take of noise as an influence of John Cage, atonality master Arnold Schoenberg’s student and arguably the most forward-thinking American composer who spent the 80s revisiting some of his older, less conventional work and writing “proper” composition, in its traditional sense. To Cage, music is made of sound and silence, but our modern life voids silence. For music to reflect life closely, any musical composition must mark that absence of silence, too. Cage furthered, as well as challenged, the definition of noise and music — and noise in music — that earlier composers such as Tchaikovsky with his cannons and Beethoven in his Fifth Symphony had been criticized for. In short, the inclusion of noise in composition both challenges and brings music closer to us.

Writing about Jackson for the acclaimed 33 1/3 book series, musicologist Susan Fast noted that Jackson’s records, “get noisier than they ever had been in the wake of hip hop’s rise as both the most significant musical development of the time and as politically-important to the Black American community.” To Fast, the inclusion of city soundscape noise in pop music is inevitable: music does not exist in a vacuum, and music of resistance such as that produced by Black musicians, hip hop in particular, has long engaged such noise. Late 80’s hip hop, wrote Black music writer and scholar Greg Tate in Jeff Chang’s Can’t Stop, Won’t Stop, was “the only avant-garde around, [who is] still delivering the shock of the new.”

Of course, noise is neither new nor exclusive to Jackson alone. Pink Floyd and Led Zeppelin each have songs that open with a scream. The Beatles put in sound made by playing with a plastic comb in “Lovely Rita.” In SM-style K-pop, Shinee’s “Shout Out” showcases monkey shrieks, f(x)’s “Milk”—a more entertaining SM-Riley collaboration—cat-and-dog chase, and Exo’s “Wolf” its titular beast.

Post “Dumb Dumb,” Red Velvet proved themselves apt to ante up the noise: animal festivity is plentiful in “Zoo,” city soundscape is restless in “Happily Ever After” and even stalkerish in “Bad Boy,” and the moaning that intersperses the Wendy and Seulgi-powered bridges in “Red Flavor” (at 0:51 and 1:46) gives the song a rather curious, connotative flavor. “Red Flavor” also makes a good example that noise, when presented right and given in the right dosage, works wonder, evident in the Beyoncé-influenced, pitched down “red, red, red, flavor,” whose technique will later be reused in the background screaming for layers in “Power Up.”

Still, Red Velvet’s best noisemaker is their voice. SM’s voice-mapping and mixing technology that is used in assigning songs to certain SM acts and parts to certain members has served Red Velvet well. To begin with, in Red Velvet’s case, tech meets touch in Wendy. There is not a day that I am not thankful for Wendy’s failing her Cube audition and finding her way to Red Velvet. Aside from the textural familiarity that “All Right,” “Butterfly,” and “Look” share with early Janet Jackson and Whitney Houston, Wendy’s hitch to a note higher in “Hear the Sea” (at 2:32) reminds me of Houston’s own for “heat” in /I wanna feel the heat with somebody/ (“I Wanna Dance with Somebody”), and this is in an admittedly challenging song to sing. Analogous to a football team with a fantasista, natural-born star, Red Velvet with Wendy is a team and a half, and Red Velvet without Wendy is a team halved. Although she is not yet on a par with Luna’s virtuosic technique or Taeyeon’s seven-times-a-divorcee song realization, Wendy’s soul leaning, strong sense of pitch, and capability for melismatic runs make the backbone of Red Velvet repertoire.

But what is a fantasista who does not have the right team? As a team, the girls use their voice to substitute the drumbeat in the last line for the chorus of “Hit That Drum” and harmonize even for a minuscule part like the bell sound effect (ding!) in “Umpah Umpah.” The linguist in me is delighted to find them utilize vocal fry as a technique in “Sassy Me,” similar to the joy I felt when discovering Regina Spektor’s use of exaggerated glottal stops in “Fidelity.” After all, it is not everyday that you see songs by women normalize the use of certain speech features for which more often than not women are scrutinized and criticized.

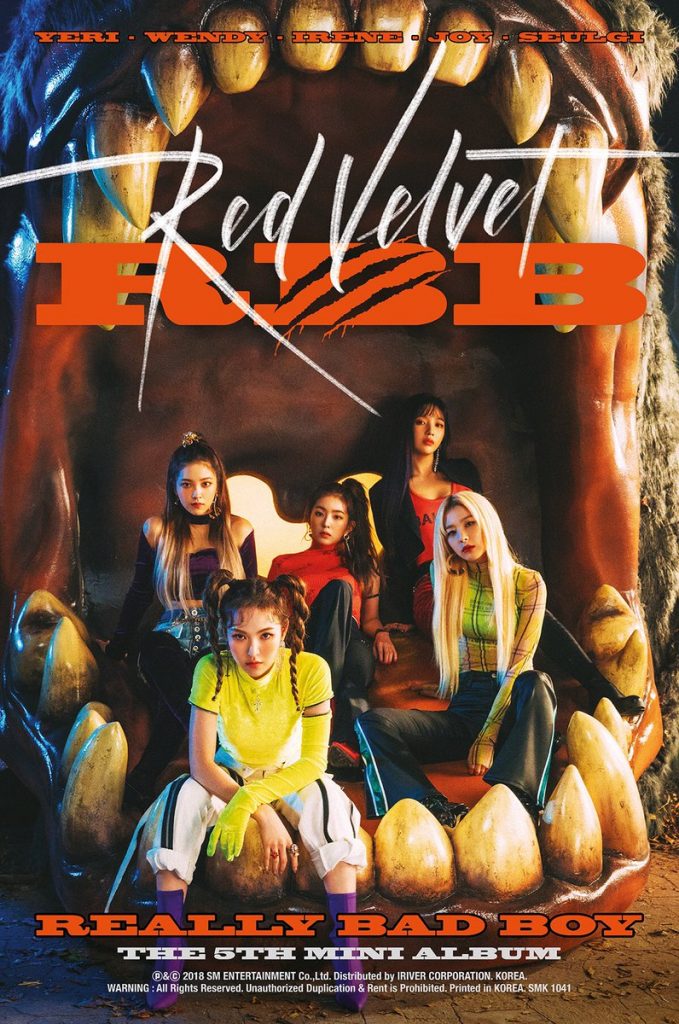

Red Velvet’s unique vocal technique also manifests itself in 2019’s most polarizing song, “Zimzalabim” which uses the girls’ voices to tinker with the registers in the chorus — the chanting chorus is done low and then high and then higher the way one would chant a mantra to oneself first and then to others and then to all. Yet, the crème de la crème is the vocal Olympics that is “RBB,” Red Velvet’s most avant-garde work so far. “RBB” is not a chart-topper and is not the friendliest sing-along number, but it marks a point in Red Velvet’s career where they prove they can make music out of cacophonies. Somewhere in their graves, Schoenberg and Cage are smiling.

As we know, the other foot of Red Velvet is made of older sounds. Much like how avant-gardism is haunted by Ezra Pound’s Modernist war cry “Make it new” that is actually a historical recycling of Medieval poetry, Red Velvet’s Velvet side falls best in line with LSM’s history with early MTV. The Velvet side makes things new by making them 80-90s American R&B. “Bad Boy,” being most exemplary of said side, is a breakout — especially in the US — because to older ears it is reminiscent of the sound of ‘90s R&B. To the younger ones, it sounds fresh because, it is generationally distant. “It’s fun,” said The Stereotypes’ Ray Romulus, “to incorporate music we grew up listening and loving but is no longer received well in the States.” With typical American Top 40 hits’ distaste of bridges, intensive chord changes, and vocal harmony—all things that make the K in K-pop, it is understandable that “Bad Boy” makes an oasis.

Even in their Red catalogue, I could not help but hear familiar notes such as Puff Daddy’s “I’ll Be Missing You,” itself a sampling of The Police’s “Every Breath You Take,” in the synth-led beat in “Power Up” verses; “Swimming Pool” reminds me of “That Thing You Do;” and even the most public-friendly number of all Red Velvet’s Red side, “Red Flavor,” slips in a little tribute to a run by Europop royalty ABBA’s “Dancing Queen,” courtesy of its composers Caesar & Loui as discussed in Netflix’s Explained—the line and instrumental combo at 00:45 and 01:38 mirrors that of /Friday night and lights are low/. Red Velvet’s effort in making things new has paid well so far, and my one note for reflection now is whether their discography, in particular the Velvet ones, is an extension, a regression, or — worse — an imitation of it.

Quo vadis, Red Velvet?

What Red Velvet have achieved in their musicality is tempered by what they have not — yet — achieved, mostly because it involves subject matters beyond their control: lyrics writing and composition. LSM-engineered idol ecosystem, itself part Motown, which the Jackson 5 underwent, and part of Japan’s entertainment emperor Johnny Kitagawa, who was also a long-time Jackson acquaintance, gets rid of socially conscious lyrics of Seo Taiji and Boys, and in its place is now lyrics and composition made by consummate specialists. Yeri and Wendy have dabbled in lyrics writing; however, considering that even Yoo Youngjin, one of the regular composers in SM rotation, had to train for three years before he was deemed capable by LSM (as reported by Korea University’s scholar and Hallyu Wave expert Park Gilsung in Korea Journal 2013), they still have a long way to go.

With SM’s pushing more challenging numbers for their NCT lines and Red Velvet, there is a clearer glimpse of the future sound that LSM is after. What I cannot figure out is where the other foot, the one standing on the shoulders of past giants, is. The little to no transitions between sections in “Zimzalabim” are truly a formal adventure, while “Umpah Umpah” is an exercise of returning to form. Yet, both are an example of standing on one foot — one too reliant on the future, the other on the past — and each risks of alienating enthusiasts of the other foot. “Sappy,” on the other hand, stands on both feet, but under-performs on the chart.

And so it goes: because K-pop is an industry that has to globalize since its domestic market cannot provide enough to support it, there is always financial concerns to address. Though not SM’s most prolific moneymaker, Red Velvet, too, is not exempt from this. However, post-SMTown Live 2019 in Tokyo, I was completely baffled as to how SM, who had Taeyeon, Luna, and Wendy on the same stage, appeared to have no inkling, if at all, to assemble them in a super project. I would love to see Red Velvet be taken seriously into SM’s business planning in addressing, for instance, JYP’s shrewd strategy of sending Twice to fill the spot that SNSD has left vacant — and Itzy for Blackpink’s infrequent appearance, on that note. And if SM were to insist on breaking into the US market still, I could not see how under-using an act who, collectively, has worked with Ricky Martin, John Legend, and Ellie Goulding is a wise decision. Red Velvet, after all, is at home with the sound of America past.

Breadwinning aside, will Red Velvet get a song where listeners keep waiting for the drop that never comes, a la f(x)’s “Red Light?” Or another song that has been shelved for years until LSM finds the most suitable group for it and picks the song up like the case of “Zimzalabim,” “Ice Cream Cake,” and even “Sappy?” Or, God forbid, one with a chorus whose texture does not feel full enough to be chorus or too minimalistic it is almost an anti-chorus?

Individual project-wise, will each member of Red Velvet be given her due room for growth? Will Irene get more chances to do EDM and Joy new jack swing, as they have stated they wanted, similar to how outside of f(x), Luna kept the European house for her solo “Free Somebody” but diverged from it when joining Amber in “Lower,” while Sulli’s “Dorothy” would have fit right in with Japanese house of Mondo Grosso kind? Both Taeyeon and SNSD have done rock-infused pop before, “Devil’s Cry” and “Mr.Mr.” respectively; can’t Red Velvet try, too, at least? In all, I am an old-school listener who likes my future rooted in its history, and I would love me some Red Velvet in that world.

Theresia Pratiwi works as a language specialist by day and moonlights as a fledgling writer. Her playlist is erratic at best and shambolic at worst. One of her wildest dreams is to see David Lynch direct a Red Velvet MV. You can find her on Twitter @thranduilion.

*Latin for I hear, I see, I learn.

(Images Via: SM Entertainment, Newsen. Baek, Seung-ah. In Korea Focus, Vol. 20 No. 1, Jan 2012 | Fast, Susan. Michael Jackson’s Dangerous. 33 1/3 Series. 2014. New York: Bloomsbury Academic | Park, Gil-sung. “Manufacturing Creativity: Production, Performance, and Dissemination of K-pop.” Korea Journal, Vol. 53 No. 4, Winter 2013 | Ep. 4: K-Pop. Explained. Netflix, 2018.)