In light of the recent Sewol ferry tragedy, it has come to the attention of many that the entire K-pop/K-entertainment industry has shut down. With reports of delayed comebacks, and promotion periods foregone, K-pop has gone in to hiding for what seems to be an unforeseeable amount of time.

In light of the recent Sewol ferry tragedy, it has come to the attention of many that the entire K-pop/K-entertainment industry has shut down. With reports of delayed comebacks, and promotion periods foregone, K-pop has gone in to hiding for what seems to be an unforeseeable amount of time.

Watching the event unfold as hours have gone by, I was astounded by the reaction of the Korean entertainment industry. Upon further digging around, I discovered that the reaction I found in K-pop was a microcosm of the collective consciences of South Korea — a national gesture of reclusion as a motion of respect for the suffering.

Looking at comments on Gaya’s post, and other various platforms on the internet, I was surprised at the reaction of a certain group of people, who felt that it was justifiable to claim — excuse the bluntness — “everyone should just get over it.” These sentiments are usually followed with responses that range from supposed “intellectual” arguments about how “tragedies occur everyday and nobody blinks an eye,” to outright offensive and rude exclaims of “who the hell cares?! I just want my album/show/concert/mv etc.”

National identity as an academic discipline, is a clouded one. So many factors weigh in on its perception and actualization, that it’s really no surprise that the above sentiments regarding Korea’s national response to the tragedy are so misunderstood. Dr Rozman (a professor at Princeton University) has noticed that over just a decade, observers have been repeatedly drawn to “bursts of expression of national identity” in South Korea. He cites the responses elicited by international events — such as the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997-98, inter-Korean summit of 2000, co-hosting of World Cup in 2002 amongst others — as tools that have grafted the national identity of entire generations of people.

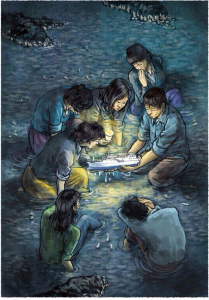

Christopher K. Chung and Samson Cho (both Doctors of Medicine at Harbor-UCLA Medical Centre) did a study on the “Significance of Jeong in Korean Culture and Psychotherapy”. They found that jeong, as a concept, is all encompassing and as a result, difficult to define. Dictionaries define it as “feeling, love, sentiment, passion, human nature, sympathy, heart etc.” Cho and Chung argue that it’s slightly more sophisticated than the former; they claim that it’s more about attachment, bond, affection or even bondage. This concept, important and quite commonly known amongst his Korean-American patients, is not even entirely definable in the Korean language. It remains ambiguous and amorphous. It’s clear however, that inter-dependency and collectivism are highly valued, in comparison to autonomy, independence, privacy, and individualism. To the individually orientated European or American, this may seem absurd, but the warm, rich interpersonal, nurturing and caring relationships that are formed as a result of acceptance in to Korean culture, makes for beautiful bonds. These alliances demand respect, loyalty, and trust, and as the expectation for the reciprocity of loyalty grows, “tremendous hurt and anger can ensue” if the connections formed by jeong are betrayed.

Christopher K. Chung and Samson Cho (both Doctors of Medicine at Harbor-UCLA Medical Centre) did a study on the “Significance of Jeong in Korean Culture and Psychotherapy”. They found that jeong, as a concept, is all encompassing and as a result, difficult to define. Dictionaries define it as “feeling, love, sentiment, passion, human nature, sympathy, heart etc.” Cho and Chung argue that it’s slightly more sophisticated than the former; they claim that it’s more about attachment, bond, affection or even bondage. This concept, important and quite commonly known amongst his Korean-American patients, is not even entirely definable in the Korean language. It remains ambiguous and amorphous. It’s clear however, that inter-dependency and collectivism are highly valued, in comparison to autonomy, independence, privacy, and individualism. To the individually orientated European or American, this may seem absurd, but the warm, rich interpersonal, nurturing and caring relationships that are formed as a result of acceptance in to Korean culture, makes for beautiful bonds. These alliances demand respect, loyalty, and trust, and as the expectation for the reciprocity of loyalty grows, “tremendous hurt and anger can ensue” if the connections formed by jeong are betrayed.

When looking at the Sewol Ferry Tragedy through this lens, the national response of hurt and anger at the government, distrust in the media and overwhelming sadness that has plagued the people of South Korea, make sense. The anger stems from many things: the government’s lack of response in rescuing the survivors, the failure to hasten the picking up of Sewol passengers, the uselessness that bystanders feel from not being able to help, and the endless waiting that families have had to endure. All of these aren’t easy pills to swallow. For those who think that this is just a matter of one tragedy amongst many others, they fail to understand the depth of hurt and betrayal the Korean people feel towards the entire issue.

The sense of guilt runs deep in a society in which profuse apologies are as commonplace as roars of victory. When the Virginia Tech Massacre was committed by young Korean-American Cho Seung-hui, South Korea collectively expressed the shame that a fellow Korean was the gunman behind the attack. President Roh Moo-hyun described his shock as “beyond description.” On the opposite end of the spectrum, a Korean-American pop star Steven Seungjun Yoo opted to become a naturalized US citizen (giving up his Korean nationality) days before he was to be drafted for his mandatory military service, effectively evading this duty. The South Korean government considered it an act of desertion, and quickly deported him and banned him from entering the country permanently. The reaction to betrayal of kin and country is a harsh one in South Korea, and right now, it’s being targeted towards the government.

Donald Kirk of Forbes notes that the air surrounding the families who have been waiting for news on a cold gymnasium floor in Jindo, is that of acceptance. The maritime disaster has brought about an amalgam of emotions; there’s rage, denial, and depression, but when the bereaved go forward to claim their relative’s bodies, bloated and decomposing, the acceptance that has to follow is entirely unbearable. For those whom the tragedy is not personal, the predominant mood is that of national shame.

Donald Kirk of Forbes notes that the air surrounding the families who have been waiting for news on a cold gymnasium floor in Jindo, is that of acceptance. The maritime disaster has brought about an amalgam of emotions; there’s rage, denial, and depression, but when the bereaved go forward to claim their relative’s bodies, bloated and decomposing, the acceptance that has to follow is entirely unbearable. For those whom the tragedy is not personal, the predominant mood is that of national shame.

Chosun Ilbo stated that “these terrible tragedies keep happening because Korean society has focused only on fast progress, while treating safety regulations as a hindrance — the government, businesses and the whole of society need to reflect on these fatal shortcomings.” From what is apparent, the reclusion of South Korea, precedes what many expect to be a tempest of accusations, allegations and lawsuits, which are likely to be be hurled at the government, and in turn profit hungry businesses.

“In tragedy, Koreans can take pride in coming together to recover from a disaster that is also a national humiliation — another form of acceptance.” This serves as an answer for those who have previously failed to understand why music shows and computer screens have gone vacant. South Korea is mourning, and they deserve all the time they need to recover.

(keia.org, prcp.org, Forbes, NYTimes, koreajoongangdaily, WSJ Blogs; Images via Wall Street Journal, Twitter)