This article contains discussions of bullying and violence, and some references to sexual assault.

This article contains discussions of bullying and violence, and some references to sexual assault.

Recently, a graphic photo of a girl kneeling on the ground covered in blood was posted on Facebook in South Korea. It went viral almost immediately. Looking at the photo, you would probably think that this girl was the victim of an attack by gangsters or other similar types of people; however, she was the victim of bullying. The CCTV showed four fellow students beating her with a chair, a metal pipe, soju bottles and snubbing lit cigarettes on her for one and a half hours. The victim was found lying unconscious on the floor, and is still hospitalised at the moment.

In the first episode of Angry Mom, the female lead’s daughter, while not as brutally attacked, ends up in a similar situation. Bullying is a serious issue in South Korea–nearly 1 in 10 students at Korean primary and secondary schools has suffered from various forms of violence at the hands of their peers, according to a survey by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology. School violence is a recurring issue highlighted in school K-dramas, and many cases provide a realistic depiction of bullying and its effects.

Often, such school dramas point to the competitive environment as one of the reasons for the high levels of bullying, portraying schools as a highly stressful setting that focuses primarily on grades. In School 2013, Victory High School is under pressure to improve its rankings, and the school in Sassy Go Go is described as vicious and being full of academic elitism. As a result, students often see each other as rivals: in School 2017, the need to be top of the cohort leads Kim Hee-chan (Kim Hee-chan), perpetually ranking second, to bully Song Dae-hwi (Jang Dong-yoon), his classmate and the top student. This reflects the fixation on education in South Korea: academic performance is regarded as a source of pride and the primary road to success. For most South Korean children, their lives revolve around education, as Yale academic Ko See-wong argues:

To be a South Korean child ultimately is not about freedom, personal choice or happiness; it is about production, performance and obedience.

I n high school K-dramas, we see this pressure from society, from family and from teachers play out–in School 2017, Hee-chan’s severe inferiority complex drives him to tries to manipulate and belittle Dae-hwi because he is unable to surpass him academically. As clinical psychologist Joo Mi-bae observes, at school students are prompted to see their peers as competition rather than friends, and feel that they need to beat them to get ahead.

n high school K-dramas, we see this pressure from society, from family and from teachers play out–in School 2017, Hee-chan’s severe inferiority complex drives him to tries to manipulate and belittle Dae-hwi because he is unable to surpass him academically. As clinical psychologist Joo Mi-bae observes, at school students are prompted to see their peers as competition rather than friends, and feel that they need to beat them to get ahead.

Another point made is that high school bullies, despite their young age, can be incredibly cruel and gangster-like. In high school dramas, the bullies tend to appear in gangs who take part in brutal bullying, a well-known example being the four male leads, F4, in Boys Over Flowers, who are the source of attempted gang rape, the spreading of extremely vicious rumours, savage beatings and so on. While this may seem too extreme to be realistic, a look at real life South Korean school violence cases highlights the chilling accuracy of such depictions.

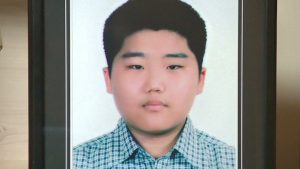

The case that provoked the current wave of public concern and focus on the issue was the 2011 bully-suicide case of Kwon Seung-min. He was subjected to water torture, his arm was nearly set on fire, and he was dragged around with an electrical cable and beaten. His bullies forced him to eat off the floor and to obtain a job to earn them money while trying to change his exam results and damage his textbooks. In the Busan assault incident referenced in the introduction, it was later found out that the victim had earlier been attacked by another group who beat her until she sustained injuries that took two weeks to heal. They also invited male students to touch her inappropriately, and she had previously been sexually harassed.

The effects of school violence can be seen in high school dramas as well. In particular, dramas also highlight how bullying contributes to high suicide rates among high school students in South Korea. In the first episode of Boys Over Flowers, a boy nearly jumps off a rooftop due to being bullied by F4 and in Angry Mom, the female lead’s daughter ends up hospitalised. These details mirror the experiences of real life bullying victims: Kwon Seung-min jumped to his death from his 7th-floor apartment, leaving behind a suicide note detailing his abuse. The victim of the Busan Assault Incident was nearly killed by the attack and was left greatly traumatised by her bullies; hospital photos showed extremely deep cuts that ripped her scalp open. Her face was left very bloated and seriously damaged by the attack.

In dramas, there is a notable pattern in the identities of the bullies: often they are either troubled students, like in Angry Mom, School 2013 and School 2017, or rich, arrogant pupils like in School 2015, School 2017 and Boys Over Flowers. While there has yet to be conclusive evidence backing up the suggestion that richer students are most likely to be bullies, there is a culture of impunity within wealthier families known as “gapjil”–the right to bully people lower on the hierarchy, to punish the weak with impunity, and to treat yourself like royalty.

In line with the claim that many bullies are troubled, a high school teacher noted that most bullies are from dysfunctional families who have been rejected and have deep anger inside. The same teacher further observed that bullying is not only a matter of school, but also a matter of family and society: in school violence, it is possible to observe the stubborn continuity of traditional hierarchical and authoritarian cultural practices.

Dramas can be a vehicle for social change: with realistic depictions of bullying that garner attention working in tandem with real-life incidents, attitudes may be changed and people, particularly those in power, may be provoked to do more about the issue. There is hope that the Busan assault incident will help create reforms in the justice system that has sheltered many students, allowing them to get away with serious crimes due to the Juvenile Act of 1995.

In a petition on the Presidential Office website calling for the Act to be scrapped, the petitioner left a poignant message: “While the victims have to live with the trauma their entire lives, the perpetrators only receive minor punishments for being adolescents… and not even a criminal record. Later in life, these past misdemeanors become mere memories of heroic exploits that they can talk about, as side dishes to their drinks. They live out in the open as adults with a laundered past.” Hopefully such actions can help to end the cycle of school violence which remains an everyday terror to many South Korean students.

(CNN, Korea Expose, Insight [1] [2] [3], The Conversation, New York Times, JTBC, Chosun TV, YouTube, Korea Times, Christian Science Monitor, Korea Herald, Canadian Centre of Science and Education, UPI.Images via KBS, CNN, MBC.)