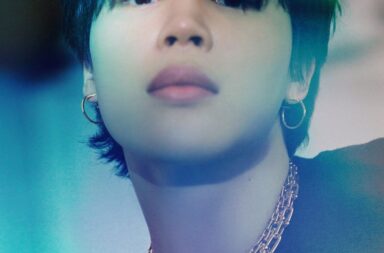

Son Ga-in of Brown Eyed Girls “shocked” the Korean public by revealing on Instagram that a friend of her boyfriend, Joo Ji-hoon, had suggested she use marijuana. Big Bang‘s T.O.P has been recently embroiled in a marijuana scandal that led to his hospitalisation over a supposed suicide attempt. The woman who was investigated with T.O.P was sentenced to four years of probation with the possibility of a three-year prison sentence if she commits a repeat offense during her probation period. The Seoul Central District Court also ordered 120 hours of drug rehab and a fee of 870,000 won (approximately $770).

Son Ga-in of Brown Eyed Girls “shocked” the Korean public by revealing on Instagram that a friend of her boyfriend, Joo Ji-hoon, had suggested she use marijuana. Big Bang‘s T.O.P has been recently embroiled in a marijuana scandal that led to his hospitalisation over a supposed suicide attempt. The woman who was investigated with T.O.P was sentenced to four years of probation with the possibility of a three-year prison sentence if she commits a repeat offense during her probation period. The Seoul Central District Court also ordered 120 hours of drug rehab and a fee of 870,000 won (approximately $770).

As an international fan, you would be forgiven for wondering why the punishment for marijuana is so harsh and the public stigma so severe in South Korea. Western stars pen odes to the drug and Instagram themselves lighting up in places where it’s legal or illegal. Meanwhile, in Korea, even smoking marijuana outside of the country and reentering can have legal consequences.

The tolerance of recreational marijuana use differs from country to country. Uruguay is the only country that has fully legalised the drug. In other places, there are varying levels of punishment and decriminalisation under circumstances such as medical use for people with chronic or terminal illness, or even possession in small amounts. In countries such as the US, punishment can vary and laws differ from state to state.

The tolerance of recreational marijuana use differs from country to country. Uruguay is the only country that has fully legalised the drug. In other places, there are varying levels of punishment and decriminalisation under circumstances such as medical use for people with chronic or terminal illness, or even possession in small amounts. In countries such as the US, punishment can vary and laws differ from state to state.

South Korea’s reputation as a ‘drug-free country’ comes from the low number of drug-related crimes recorded. Internationally, the qualification of a drug-free country is whether there are more than 10,000 narcotics-related convictions. Drug related arrests in South Korea in 2011 amounted to just over 7,000. In 2014 that number was 9,742.

The approach to creating this society, from a governmental perspective, is to punish offenders and suppliers harshly, according to the Korean Institute of Criminology’s Cho Byung-in, who described Korean drug laws as “sufficeintly strict and effective.” In addition, he states:

Despite the fact that no state has yet been fully successful in the ‘war on drugs,’ I believe that not only illegal drug traffickers but also illegal users should be strictly punished to maximise the deterrence effect.

The punitive policy is disputed to the main reason for the successful suppression of narcotics use — social influence is important. “(The) war on drugs is almost an annual event whenever drug usage becomes a social problem,” said Hwang Sung-hyun, a professor of criminology at Cyber University. “I don’t think it’s necessarily effective. The reason why Korea is a drug-free country is the result of the people’s strong rejection of dealers and suppliers, not because of a strong and effective drug policy, necessarily.”

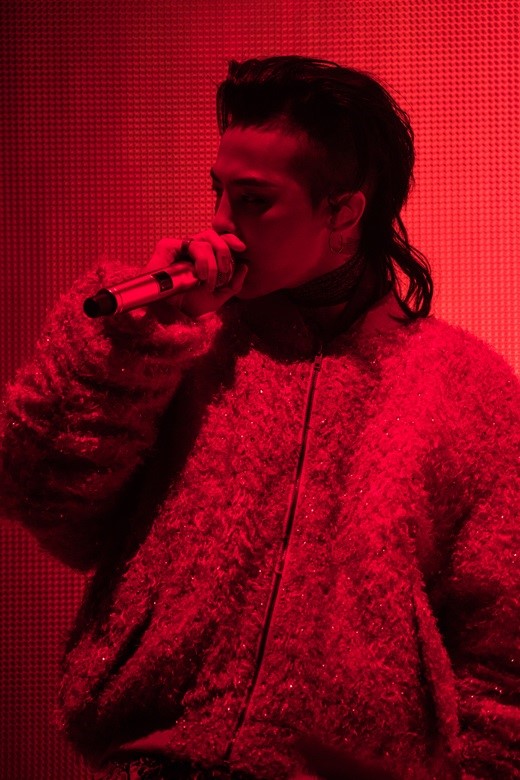

The social consequences of drug involvement can be significant. YG Entertainment recently earned the nickname “Yak Guk,” or Korean for “drugstore,” after T.O.P’s charges emerged publicly. Analyst Lee Ki-hoon said T.O.P’s scandal affected band mate G-Dragon’s recent solo album release as he was previously charged with the same crime. “The fall in YG’s stock price is not due to T.O.P, but because of G-Dragon,” said Lee in an interview with local press. “G-Dragon had the same marijuana issue in the past and T.O.P admitted his crime a week before G-Dragon’s comeback. “The scandal has caused G-Dragon’s case to resurface and people want to find out the truth on G-Dragon’s scandal too,” added Lee.

The social consequences of drug involvement can be significant. YG Entertainment recently earned the nickname “Yak Guk,” or Korean for “drugstore,” after T.O.P’s charges emerged publicly. Analyst Lee Ki-hoon said T.O.P’s scandal affected band mate G-Dragon’s recent solo album release as he was previously charged with the same crime. “The fall in YG’s stock price is not due to T.O.P, but because of G-Dragon,” said Lee in an interview with local press. “G-Dragon had the same marijuana issue in the past and T.O.P admitted his crime a week before G-Dragon’s comeback. “The scandal has caused G-Dragon’s case to resurface and people want to find out the truth on G-Dragon’s scandal too,” added Lee.

Public stigma around marijuana can be traced to a political shift in legislation that happened in the ’50s with the introduction of the Narcotics Act. Prior to this shift, hemp, known locally as daemacho, was grown in rural areas but there isn’t a lot of confirmed history about its recreational use. The crop was versatile, used to make ropes, nets and fabric. Its seeds were used as a laxative in traditional medicine. The Narcotics Act was influenced by a US push for control of the flow of opiates, driven by the Federal Bureau of Narcotics and Harry J. Anslinger. US propaganda on marijuana was alarmist and their approach to control was to criminalise dealers and users, punishing them severely.

Park Chung-hee, ex-president Park Geun-hye’s father and South Korea’s longest-reigning military dictator (1961-1979), led the administrative charge against marijuana. The hippy movement of the ’60s was considered to be a degenerative cultural influence by the Park regime and marijuana was viewed as a marker of that degeneration.

At this grave juncture that will settle the matter of life and death in our one-on-one confrontation with the Communist Party, the smoking of marijuana by the youth is something that will bring ruin to our country. — President Park Chung-hee, Feb. 2, 1976

The Narcotics Act was insufficient for the administration so it was complemented by increasingly severe punishment for the use of ‘habit forming medicine’, toxic chemicals, and psychotropic substances. The Cannabis Control Act (CCA) was written into law in 1976. It outlawed not only the smoking and possession of marijuana in general, but also imposing strict regulations on all aspects of the hemp industry. The CCA was accompanied by anti-marijuana propaganda films and severe punishment meted out to celebrities, particularly those who seemed to glamourise the use of the drug. Psychedelic rockstar, Shin Joong-hyun was arrested for possession of marijuana in 1975, tortured in prison and incarcerated in a psychiatric hospital.

The propaganda surrounding the use of narcotics seem to implicate foreign influences as the motivating factor to why Koreans would use cannabis — the “Marijuana Crisis of 1975” was centred around weed smoking near US military bases and in clubs frequented by foreign soldiers. According to Lee Chang-ki’s book The Story of Drugs (2004), Koreans first started smoking cannabis only after it was introduced to them by American soldiers. Japanese colonial rule and North Korean destabilisation conspiracies were also named as influences to why people in South Korea would indulge in substance abuse.

The propaganda surrounding the use of narcotics seem to implicate foreign influences as the motivating factor to why Koreans would use cannabis — the “Marijuana Crisis of 1975” was centred around weed smoking near US military bases and in clubs frequented by foreign soldiers. According to Lee Chang-ki’s book The Story of Drugs (2004), Koreans first started smoking cannabis only after it was introduced to them by American soldiers. Japanese colonial rule and North Korean destabilisation conspiracies were also named as influences to why people in South Korea would indulge in substance abuse.

Media attitudes to the use of illegal substances are still criticised for focusing on foreign influences. Expats derided press surrounding a 2015 drug bust claiming reporters placed emphasis on perpetrators’ overseas stay, reported unconfirmed allegations about customers’ nationalities, and inflated the value of the bust. When asked why the Korean media called the incident “a raid against overseas students”, Moon Jeong-up, a police officer, said that the vast majority of the customers who were booked without detention were overseas students. “I’d say over 70 percent of his customers were from abroad and they were from countries like the US, Australia, Britain, Canada, Brazil, New Zealand and Ecuador,” he said.

T.O.P.’s arrest and the very public scrutiny of Ga-in’s claims may play into an existing narrative of entertainers morally corrupted by foreign influences and serve to reinforce the public stigma against marijuana. T.O.P.’s case may in fact mirror those of other entertainers who have been held up as examples showcasing the life-altering, negative consequences of drug use. While marijuana is criminalised to a large degree all over the world, the politically motivated stigma created by the Park regime’s influence maintains its hold in modern times.

(Korea Times [1][2][3][4], Korean Herald, Korea Expose [1][2], Nate, Naver, The Guardian [1][2], Korean Observer [1][2], Yonhap News, Drug Control Policy in Korea, YouTube, Images via APOP Entertainment, Pixabay, YG Entertainment)