For anyone who has been part of the K-pop fandom for a considerable time, the term ‘comfort women’ shouldn’t sound unfamiliar. Ranging from fleeting mentions to being in the spotlight of idol activism, ‘comfort women’ have been referred to as an issue, as dismissed history, and as a cause of rift between South Korea and Japan. Time and again, ‘comfort women’ have been portrayed as a monolith of victims forced into sexual slavery by Japan to act as receivers of violent and gruesome display of imperialist power.

For anyone who has been part of the K-pop fandom for a considerable time, the term ‘comfort women’ shouldn’t sound unfamiliar. Ranging from fleeting mentions to being in the spotlight of idol activism, ‘comfort women’ have been referred to as an issue, as dismissed history, and as a cause of rift between South Korea and Japan. Time and again, ‘comfort women’ have been portrayed as a monolith of victims forced into sexual slavery by Japan to act as receivers of violent and gruesome display of imperialist power.

As Japan shamelessly argues over the rightness of the apology offered to these women in the Kono Statement, it is imperative to make sure that unlike several nationalist discourses in South Korea, the issue should not be diffused into and universalized as a ‘national’ matter that imposes the symbolic meaning of the nation upon women’s sexually violated bodies, relegating them as a homogenous whole and destroying any chance of redefinition by ‘comfort women’.

Instead of killing their agency and rendering them as disembodied voices in male authored texts, it is important to realize that these ‘comfort women’ have individual pasts and stories to narrate; they are not symbols of a bloody past neither are they pawns of nationalist policies. They are women whose real exploitation was and has been contingent on gender, economic and national identity.

Kim Eun-shil in her essay “Women and Discourses of Nationalism: Critical Readings of Culture, Power and Subject,” analyzes the silence of ‘comfort women’ through the lens of South Korean feminism. She asserts that since the purity and virginity of women was symbolic of the nation, the organized sexual slavery of women was seen as the rape of the country by the Japanese, evoking visceral reaction from male citizens of Korea to defend the ‘sullied’ honour of their nation. On the other hand, Japan viewed ‘comfort women’ as either war trophies or available resources of the colonized country. As a result, the notion of ‘dishonour’ draws its reference from the ‘violation’ of bodies; honour is rendered as a fragile sentiment embodied only by the body of a woman which is why there was a tense silence regarding the issue of comfort women for 50 years after Japan had left South Korea, with people regarding comfort women as ‘polluted’ and ‘dirty’, and pushing them further to the margins.

Kim Eun-shil in her essay “Women and Discourses of Nationalism: Critical Readings of Culture, Power and Subject,” analyzes the silence of ‘comfort women’ through the lens of South Korean feminism. She asserts that since the purity and virginity of women was symbolic of the nation, the organized sexual slavery of women was seen as the rape of the country by the Japanese, evoking visceral reaction from male citizens of Korea to defend the ‘sullied’ honour of their nation. On the other hand, Japan viewed ‘comfort women’ as either war trophies or available resources of the colonized country. As a result, the notion of ‘dishonour’ draws its reference from the ‘violation’ of bodies; honour is rendered as a fragile sentiment embodied only by the body of a woman which is why there was a tense silence regarding the issue of comfort women for 50 years after Japan had left South Korea, with people regarding comfort women as ‘polluted’ and ‘dirty’, and pushing them further to the margins.

She further complicates the experience of ‘comfort women’ by bringing in silent voices i.e., testimonies which show the complicit participation of Korean men in the organized torture of ‘comfort women’:

“Their testimonies include stories of leaving homes for Japan to make money; being swindled by Korean men; unbearable imperialist powers wielded on their bodies through sexual violence, physical abuse and confinement; wishing for Japanese victory at war to be paid back their wages for prostitution; and honest depictions of contemporary Korean situation when ex-comfort women could not stay in marriage due to infertility caused by severe damage to their sexual organs, or could not support themselves because of poverty etc.”

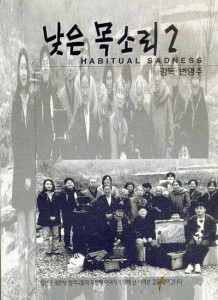

This painful legacy of Japanese colonization escapes from the academic sphere and gets embedded in celluloid as independent filmmakers like Pyon Yong-ju link the past of ‘comfort women’ with present day construction of femininity through her films The Murmuring and its sequel Habitual Sadness. Breaking from the common representations of ‘comfort women’ as either desexualized or hyper-sexualized, the movies have comfort women’s voices reverberating in a hall familiar to a skewed narration of history. It reflects upon how the current stress on hyper-femininity, ‘purity’, ‘chastity’, ‘virginity’ has its root in the treatment of ‘comfort women’, how the very construction of femininity comes with the implicit knowledge of being guarded by hyper-masculine protection.

While The Murmuring is confessional in nature, Habitual Sadness is confessional on a whole different level as Kang Tok-kyong, a former comfort woman herself asked the director to document the lives of ‘comfort women’ throwing herself into the filming process. Instead of playing the blame game, Habitual Sadness focuses on something far more pressing – Self healing. The movie deals with former comfort women gaining the courage to face their past, to not be daunted by society and literally, talk about it, to vocally share their grief and suffering emphasizing that in the ping-pong nationalist politics of South Korea and Japan, it is these surviving ‘comfort women’ who take the brunt of the delay, deliberation, along with suffering from severe under representation in the political sphere. And they can’t keep on bearing the delay and insensitivity meted out to their misrepresented identity. As South Korea’s president Park Geun-hye mentioned, time is running out as only 55 of the 237 South Korean women who have spoken out about their painful experiences are still alive.

While The Murmuring is confessional in nature, Habitual Sadness is confessional on a whole different level as Kang Tok-kyong, a former comfort woman herself asked the director to document the lives of ‘comfort women’ throwing herself into the filming process. Instead of playing the blame game, Habitual Sadness focuses on something far more pressing – Self healing. The movie deals with former comfort women gaining the courage to face their past, to not be daunted by society and literally, talk about it, to vocally share their grief and suffering emphasizing that in the ping-pong nationalist politics of South Korea and Japan, it is these surviving ‘comfort women’ who take the brunt of the delay, deliberation, along with suffering from severe under representation in the political sphere. And they can’t keep on bearing the delay and insensitivity meted out to their misrepresented identity. As South Korea’s president Park Geun-hye mentioned, time is running out as only 55 of the 237 South Korean women who have spoken out about their painful experiences are still alive.

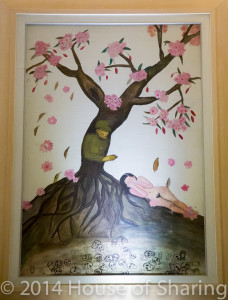

Housing some of these surviving ‘comfort women’ is the “House of Sharing” museum, located in Gwangju, on the outskirts of Seoul. While it acts as a place of comfort, solace and shared understanding creating a sisterhood of former ‘comfort women,’ it is also a visual representation of the stigma associated with organized rape. The house becomes emblematic of every wrong done against these women by a variety of perpetrators; as unlike the euphemistic nature of the term ‘comfort women’, this house with its residents stands as a blatant reminder of a dreadful past. From being a refuge, this house has been transformed into a museum recording personal history and redefining identities.

The former ‘comfort women’ have taken to art to express their anguish and rewrite discourses, however, even their own discourses show strains of patriarchal and nationalist ideologies as represented by the painting “Deprived Purity” ricocheting images of patriarchal conceptions of womanhood and purity. However, for someone who has been force fed patriarchal and imperialist ideologies for years, the very act of painting what she deems as depriving purity is a highly commendable feat in itself. The most amazing part of such documentation is the stratification they bring into the term ‘comfort women.’ They are no longer ‘comfort women’; they are Bea Chun-hui, Kang Tok-kyong, women with individual names, individual pains, and individual stories.

The former ‘comfort women’ have taken to art to express their anguish and rewrite discourses, however, even their own discourses show strains of patriarchal and nationalist ideologies as represented by the painting “Deprived Purity” ricocheting images of patriarchal conceptions of womanhood and purity. However, for someone who has been force fed patriarchal and imperialist ideologies for years, the very act of painting what she deems as depriving purity is a highly commendable feat in itself. The most amazing part of such documentation is the stratification they bring into the term ‘comfort women.’ They are no longer ‘comfort women’; they are Bea Chun-hui, Kang Tok-kyong, women with individual names, individual pains, and individual stories.

Giving their stories a much needed political punch and re-contextualizing them to broaden their issues and make them more relevant to current history is Lee Chang-jin’s recent exhibition “Comfort Women Wanted.” A five year art project, Lee Chang-jin gives tangible shape to humiliation as she recreates the ambience of women under the siege of sexual violence by imperial powers through the medium of reconstructed advertisement posters for comfort women, a video featuring interviews of Korean, Chinese, Taiwanese, Indonesian, Filipino, and Dutch ‘comfort women’ survivors, and a former Japanese soldier, each speaking about their experiences at military ‘comfort stations,” as well as about their own hopes and dreams, and a reconstructed ‘comfort station.’

To hear and see stories of former ‘comfort women’ from relatively privileged positions in life is one sort of experience but to undergo a simulation of the life of ‘comfort women’ is the hardest way reality can hit your conscience. It makes one realize that rape and torture were not the only humiliation; there was subtle violence at work too, a violence which was inflicted upon women when posters imagined them as sex objects to be sold, when they found themselves helpless against their torture, when their ‘new life’ consisted of only being guinea pigs to experiments of power – these other sufferings compounded the often simplified issue of rape of ‘comfort women.’

[youtube http://youtu.be/PmBgiLA0Ddo]The biggest leap which Lee Chang-jin takes in the re-conceptualization of the ‘comfort women’ issue is that she re-imagines it to encompass the larger issue of human trafficking. She asserts that the history of comfort women is one of the many causes why human trafficking although illegal is still validated in society, that under-privileged women and children being whisked off to foreign places to serve as sex slaves is not something frozen in some obscure page of a history textbook but has continued to exist over time.

South Korea cannot act as if its house is squeaky clean while putting the blame completely on Japan’s shoulders when it itself deals with a new form of ‘comfort women’ also known as the organized practice of ‘mail-order brides.’ Targeting financially deprived young brides who are expected to be docile and submissive to their patriarchal norms and silently endure domestic violence, South Korean men are at the verge of imitating their former imperialist ruler from tip to toe. In the broad culture of human trafficking, if South Korea has been a victim, it has also been and continues to be a perpetrator.

One of the biggest projects undertaken by ‘comfort women’ is the correct representation of their history and the naturalization of the same, and what better way to approach it than the popular culture of graphic novels. “The Flower That Doesn’t Wilt: I’m the Evidence” was an exhibition at the National Museum of Korean Contemporary History in Seoul on March 1, 2014 of graphic novels authored by comfort women. It was first showcased in Angoulême International Comics Festival in France, and managed to ruffle several Japanese feathers with its unbridled stories of pain and suffering. The subject of “the flower which doesn’t wilt” is interesting because instead of gentility and vulnerability, the un-wilting flower now symbolizes steely perseverance.

One of the biggest projects undertaken by ‘comfort women’ is the correct representation of their history and the naturalization of the same, and what better way to approach it than the popular culture of graphic novels. “The Flower That Doesn’t Wilt: I’m the Evidence” was an exhibition at the National Museum of Korean Contemporary History in Seoul on March 1, 2014 of graphic novels authored by comfort women. It was first showcased in Angoulême International Comics Festival in France, and managed to ruffle several Japanese feathers with its unbridled stories of pain and suffering. The subject of “the flower which doesn’t wilt” is interesting because instead of gentility and vulnerability, the un-wilting flower now symbolizes steely perseverance.

Of the many reasons why Japan may have been upset over the exhibition of these graphic novels on an international podium apart from the recorded “a mistaken point of view that further complicates relations between South Korea and Japan” is that the use of graphic novels melts the frame of time around the issue and allows it travel through time and space, reaching out to people of all ages and nationalities. By embedding it in popular culture, it stirs popular awareness and imagination, urging popular protest against the issue. The images, which do not follow the typical exaggerated drawings of contemporary graphic novels, are not very realist in nature which creates the idea that the person in the story could have been someone we knew, and that this protagonist faces the risk of featuring in such a gruesome story even today.

Of the many reasons why Japan may have been upset over the exhibition of these graphic novels on an international podium apart from the recorded “a mistaken point of view that further complicates relations between South Korea and Japan” is that the use of graphic novels melts the frame of time around the issue and allows it travel through time and space, reaching out to people of all ages and nationalities. By embedding it in popular culture, it stirs popular awareness and imagination, urging popular protest against the issue. The images, which do not follow the typical exaggerated drawings of contemporary graphic novels, are not very realist in nature which creates the idea that the person in the story could have been someone we knew, and that this protagonist faces the risk of featuring in such a gruesome story even today.

This generalizing across time and space while keeping the voices of ‘comfort women’ intact gives a new dimension to the term itself; from evoking images of tortured soul, ‘comfort women’ has now come to symbolize a powerful political group of women who demand justice. To call them ‘poor’ women is a gross insult since not only do we render them as defenseless but we also disregard the amount of work they have done in the defense of their own cases.

What the former ‘comfort women’ demand is only not an apology. Much harm has been done overtime and continues to be done, and it can only be compensated if history is narrated in their voices. Their silence, in that horrendous era of torture, should not be something which students of history feel comfortable glossing over but instead should feel deafened by. History needs to be rewritten and distributed among the masses in such a way that both the silence(s) and voice(s) of individual women reverberate through all important documents. It’s all very fine and much appreciated when idols like Jonghyun, Yoseob, and Suzy come to support the cause of comfort women but it is even more important that it is not their voices alone we should be listening for: instead their voices should guide us to the voices of the historically, politically and economically neglected ‘comfort women.’

(Youtube [1] The Granite Tower, Bloomberg, Taipei Times, New York Times, Huffington Post, Anklebiter Photography, Japan Today, KOREA, Edited by Kim, Eun-shi and Chang, Pil-wha. Women’s Experiences and Feminist Practices in South Korea. Edited by McHugh Kathleen and Abelmann, Nancy. South Korean Golden Age Melodrama: Gender, Genre, and National Cinema. Images via Lee Chang-jin, House of Sharing, National Museum of Korean Contemporary History)