At this point, it is probably fair to say that everybody who is at least somewhat attuned to the K-popiverse has seen the infamous picture of a “sick” IU and the inexplicably shirtless Eunhyuk that was accidentally leaked to the public through the former’s Twitter account. As my fellow writer Patricia noted, the feeble explanation offered by LOEN Entertainment (and more or less backed up by the folks at SM Entertainment) fooled approximately no one into thinking that Eunhyuk had deliberately put himself in a contagion’s path by visiting an ill friend and then taken a picture for posterity — and whether the allegations are true or not, the public’s general consensus is that the two have engaged in ::whispers:: sexual activity. Now, really, it isn’t much of a surprise — as Eunhyuk might say, it’s because he naughty naughty (hey — he’s Mr. Simple!).

At this point, it is probably fair to say that everybody who is at least somewhat attuned to the K-popiverse has seen the infamous picture of a “sick” IU and the inexplicably shirtless Eunhyuk that was accidentally leaked to the public through the former’s Twitter account. As my fellow writer Patricia noted, the feeble explanation offered by LOEN Entertainment (and more or less backed up by the folks at SM Entertainment) fooled approximately no one into thinking that Eunhyuk had deliberately put himself in a contagion’s path by visiting an ill friend and then taken a picture for posterity — and whether the allegations are true or not, the public’s general consensus is that the two have engaged in ::whispers:: sexual activity. Now, really, it isn’t much of a surprise — as Eunhyuk might say, it’s because he naughty naughty (hey — he’s Mr. Simple!).

I’m sorry about that. Someone had to say it.

Reactions to the news have largely centered around the obvious disconnect between IU’s (completely unrealistic, totally company-concocted) image as fully developed women with the experiences and attitude of a six-year-old child and the apparent reality of IU as a fully developed women who does the sort of things that fully developed women do — and those sorts of things sometimes (but not always) involve copulating with members of the opposite sex. But as Patricia discussed in her article, a lot of international fans put their proverbial two cents into the debate without first understanding how South Korean society itself understands sex — and therefore interpreted the scandal in a South Korean context that pretty much doesn’t exist. If South Koreans are in any way surprised that two youngsters (and let’s be real, Eunhyuk is not that young) are having sex, they really oughtn’t be; even though sex as a subject of popular discussion might still be somewhat taboo, the thriving sexuality of South Korea’s adolescent and young adult population is obvious enough if you know where to look. In other words, it is more or less true that South Korea has yet to engage in a wide-scale social dialogue on sexual issues — but that doesn’t mean that South Korean society is sex-averse or attempting to collectively fool itself into thinking that only married adults with biological reproduction in mind are doing the deed.

So how does sex silently (and not-so-silently) manifest itself in South Korean society? And how does South Korean law rule on hot-button issues pertaining to women’s health, reproduction, and sexuality?

Let’s get started.

It’s fair to say that young people in South Korea who want to have sex might not have it as easy as do their counterparts in, say, the United States. While a significant number of Americans over the age of 18 leave home to attend an out-of-state college or move out of their parents’ house, many (if not most) college-aged South Koreans are still living at home. This is the result of a confluence of factors; while one of them would definitely be a societal norm that discourages moving out of one’s natal home until marriage, perhaps the most obvious is that South Korean universities tend to be located in cities, which is (surprise!) where most South Korean people are also located. The Seoul metropolitan area is home to more than half of the South Korean population, and the plethora of universities located throughout the city and its suburbs means that most students will attend a college that is just a subway or bus ride away from their parents’ homes and thus have no compelling reason to move out. While most colleges have dormitories, they tend to host only students who are from other cities and are often governed by rules strict enough to make an American college student cringe. Here, I refer to stringent sex segregation (no boys allowed on all-girl floors under any circumstances, and vice-versa), 1AM curfews, lockouts, and heavy supervision. Ergo, students living either with their parents or in a dorm (and these comprise the grand majority of South Korean students) are a bit out of luck if they want to squeeze in a romp with their partner.

This, however, doesn’t mean that South Korean youngsters have just shrugged off the possibility of having sex; rather, a vibrant industry of pay-by-the-hour motels (known in popular parlance as “love motels”) has sprung up to provide individuals who would like to have some privacy to get down with a place to do so. Love motels are often located near universities (understandably, to cater to a young population of horny kids with nowhere to go) and are marked by their neon lights, ostentatious decorations, creative themes (this writer once saw what appeared to be a superhero-themed love motel featuring a life-size Spiderman statue sporting an impossibly large phallus), and signs advertising hourly rates. While love motels have earned a rather seedy reputation among international K-pop fans, the fact of the matter is that they are not being used only by depraved or gross perverts; really, young South Koreans who are involved in healthy relationships really have no other recourse if they want to physically manifest their feelings for one another. Love motels, as sketchy as they may sound to the international audience, are filling what I think is a necessary void in South Korea — and while they get a lot of flack for not being the most sanitary of places, chances are that they are more sanitary than other locations out-of-luck couples might choose. Curious about love motels? After The Girl in My Sassy Girl passes out on the subway, Gyeon-woo takes her to a love motel that charges him 40,000 won (~$35) for the night.

This, however, doesn’t mean that South Korean youngsters have just shrugged off the possibility of having sex; rather, a vibrant industry of pay-by-the-hour motels (known in popular parlance as “love motels”) has sprung up to provide individuals who would like to have some privacy to get down with a place to do so. Love motels are often located near universities (understandably, to cater to a young population of horny kids with nowhere to go) and are marked by their neon lights, ostentatious decorations, creative themes (this writer once saw what appeared to be a superhero-themed love motel featuring a life-size Spiderman statue sporting an impossibly large phallus), and signs advertising hourly rates. While love motels have earned a rather seedy reputation among international K-pop fans, the fact of the matter is that they are not being used only by depraved or gross perverts; really, young South Koreans who are involved in healthy relationships really have no other recourse if they want to physically manifest their feelings for one another. Love motels, as sketchy as they may sound to the international audience, are filling what I think is a necessary void in South Korea — and while they get a lot of flack for not being the most sanitary of places, chances are that they are more sanitary than other locations out-of-luck couples might choose. Curious about love motels? After The Girl in My Sassy Girl passes out on the subway, Gyeon-woo takes her to a love motel that charges him 40,000 won (~$35) for the night.

Sex education in South Korean schools unfortunately seems to mimic the general lack of society-wide discussion about sexual issues; while sex education is a part of school curriculum, there have been numerous complaints that it has been inadequate, impractical, and essentially useless. Students report an over-reliance on ineffective metaphors and a lack of emphasis on the implications of unsafe sex. Despite weak government attempts at reforming the system, a survey of students attending Yonsei University in Seoul reports that 85.6% of students feel that current methods of sex education are unsatisfactory — and since parents may not be terribly enthusiastic about or willing to have the “birds and bees” talk with their kids (this is not just a Korean thing, by the way — parental squeamishness about sex is, I’m pretty sure, universal), this results in young people learning about sex from the media. And that…is just not ideal. Additionally, weak sex education has partially contributed to skewed perceptions about the need to be vigilant in regard to one’s sexual health. Many South Korean women are still under the impression that the gynecologist is a place that you visit only when you are pregnant, and many do not bother to schedule even a routine checkup until pregnancy necessitates a visit.

This lack of effective communication in a variety of environments — in the home, at school, and in society at large — has manifested itself in some potentially unsafe legal decisions regarding sex and contraception. Abortion is illegal in South Korea, except in life-threatening cases, and doctors face heavy prosecution if they perform abortions as a means of birth control. This does not necessarily mean that birth control abortions don’t happen (they do), but it does leave women bereft of a safe and legal way of procuring an abortion should a woman decide she wants one. Additionally, the birth control pill is available over-the-counter at any pharmacy and does not require a prescription or a visit to the gynecologist in order to get it. While this does enable younger women who are afraid of possible parental overreaction or disapproval to get their hands on a fairly safe contraceptive, the fact that one can purchase a pill that requires following very specific instructions (and one that could have dangerous side-effects) without first consulting a medical professional is risky indeed. Interestingly enough, the morning-after pill is only available with a prescription — and despite the fact that the South Korean government attempted to introduce legislation that would reverse this (making the birth control pill a prescription-only medication and turning the morning-after pill into an over-the-counter item), the status quo currently prevails.

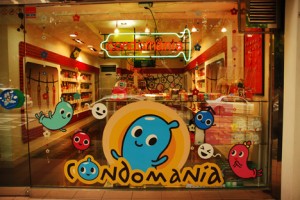

For the fellas (and the ladies, too), condoms are available at drugstores, convenience stores, and a few stores that are valiantly attempting to encourage safer sex by being dedicated exclusively to the sale of condoms. One such store, called Condomania, is located near Ewha Woman’s University in Seoul. While Condomania does come off as a bit of a novelty shop, you can’t fault them for trying — and any excuse to get people to purchase condoms is probably a good one, even if it is just a gag. You never know when that Pikachu-shaped condom might come in handy!

For the fellas (and the ladies, too), condoms are available at drugstores, convenience stores, and a few stores that are valiantly attempting to encourage safer sex by being dedicated exclusively to the sale of condoms. One such store, called Condomania, is located near Ewha Woman’s University in Seoul. While Condomania does come off as a bit of a novelty shop, you can’t fault them for trying — and any excuse to get people to purchase condoms is probably a good one, even if it is just a gag. You never know when that Pikachu-shaped condom might come in handy!

Finally, to address what might be the greatest source of misconception surrounding the HyukU (IHyuk?) scandal, the age of consent in South Korea is actually 13 — so even if the photo of IU and Eunhyuk was indeed taken in 2010, before IU was legally considered an adult in South Korea, the purported sex that netizens are so convinced took place would not have been illegal (provided it was consensual). Sounds unbelievable that a society with such a poor track record for (a) talking about sex, (b) educating its students about sex, and (c) ensuring safe sex for both genders would have one of the lowest ages of consent that I’ve ever heard, but I guess that’s what they call irony.

I hope that we’ve been able to clear up some common misconceptions and misunderstandings about sex in South Korea. Really, South Korea is not an overly conservative society when it comes to sexual matters — it just hasn’t quite gotten comfortable talking about them in a productive manner yet. If you have further questions or comments, leave them below!

(The Grand Narrative [1] [2], Gusts of Popular Feeling)