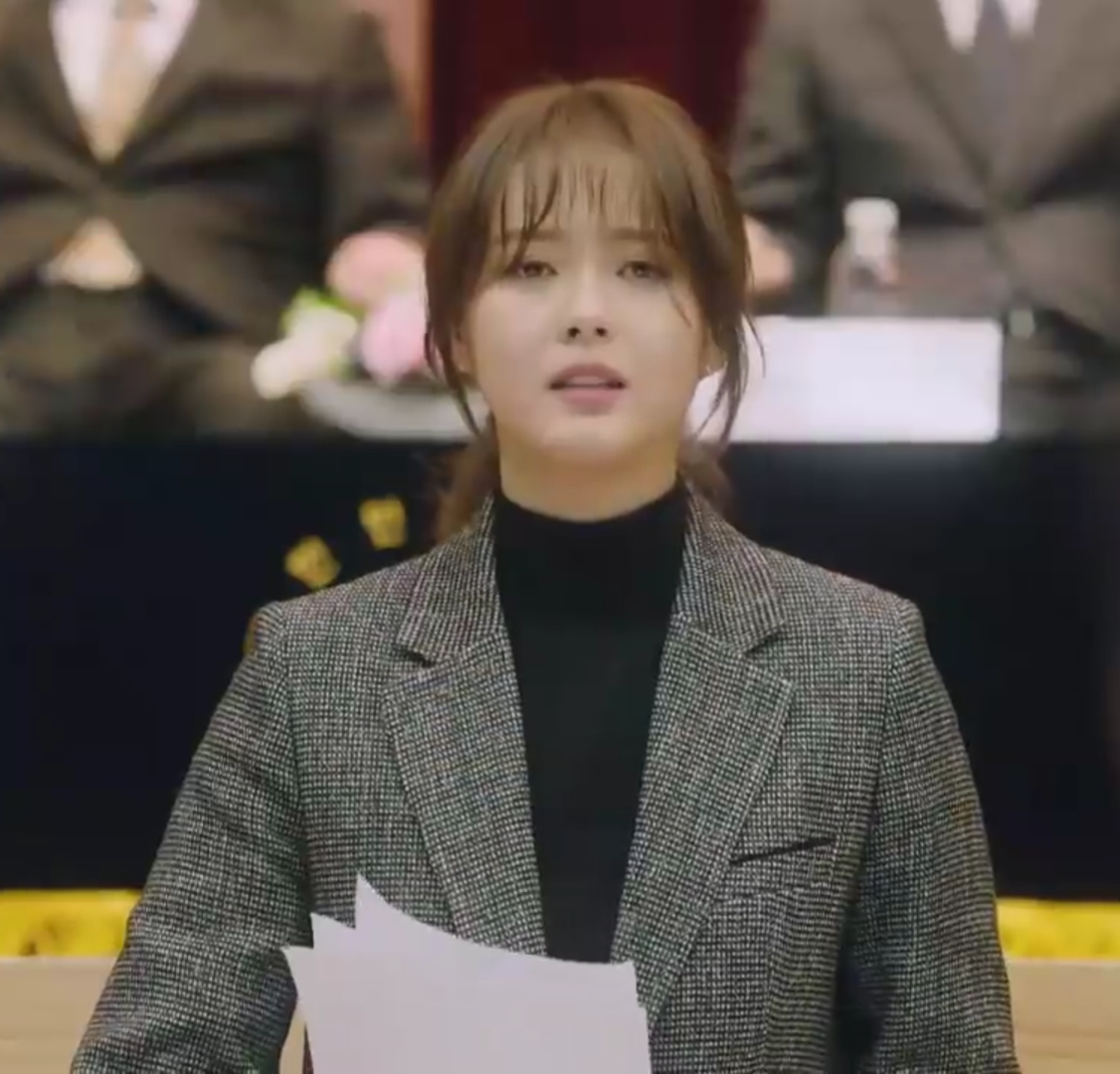

Numerous Korean dramas have tried to subvert the image of a helpless female protagonist waiting for her knight in shining armour, but none have done it in quite the same manner Miss Hammurabi has. Unlike the stubborn and strong-headed female leads with awesome martial arts abilities (think Park Shin-hye in Doctors, or Han Ye-ri in Switch: Change the World), Miss Hammurabi presents Park Cha Oh-reum (played by Go Ara) as a kind yet determined judge. Going beyond female stereotypes, the courtroom drama has masterfully addressed a host of societal questions since its start. Even though its only halfway through its run, it certainly leaves viewers contemplating South Korea and its judicial system.

Numerous Korean dramas have tried to subvert the image of a helpless female protagonist waiting for her knight in shining armour, but none have done it in quite the same manner Miss Hammurabi has. Unlike the stubborn and strong-headed female leads with awesome martial arts abilities (think Park Shin-hye in Doctors, or Han Ye-ri in Switch: Change the World), Miss Hammurabi presents Park Cha Oh-reum (played by Go Ara) as a kind yet determined judge. Going beyond female stereotypes, the courtroom drama has masterfully addressed a host of societal questions since its start. Even though its only halfway through its run, it certainly leaves viewers contemplating South Korea and its judicial system.

The following contains mild spoilers for Miss Hammurabi episodes 1-9.

The drama is based off a serial novel by Moon Yoo-seok, a senior judge of the Seoul Central District Court. Moon is also responsible for the drama’s script, which is infused with intricate dealings regarding Korea’s law. Deviating from usual courtroom dramas that tend to focus on murder mysteries and other sensational crimes, Miss Hammurabi focuses on the everyday. The drama becomes much more relatable and human simply by spotlighting the ongoings in civil court.

Even before we step into the courtroom, Oh-reum’s entrance onscreen delivers a strong message against everyday acts perpetuating gender inequality. Clips of the first episode have since been circulating online, gaining even more popularity for the show. She not only spreads her own legs outwards on the subway as a subtle protest against the ever-detestable man-spreading, silences an obnoxious lady speaking too loudly on the phone, but even goes to the extent of defending a female student from sexual harassment. As a female viewer, it was hard not to clap for her courage and level-headedness in dealing with such behaviour.

Her actions cause an uproar as she begins her first day at work as the left-hand judge to Han Se-sang, played by Sung Dong-il. Many might know Sung Dong-il for his comedic performances in dramas such as the Reply series; he is equally brilliant in Miss Hammurabi. In this drama, he portrays a short-tempered but ultimately warmhearted presiding judge of the civil case department. However, he does come into conflict with his new left-hand judge.

From the very start, Oh-reum gets into a squabble with Se-sang about female dress codes. This eventually leads to her heading to work in a mini skirt, before she changes out into an attire that covers her from head-to-toe. Intending to make a statement, but also to spite Se-sang, it is at once hilarious but also hard-hitting. She earns the title “Miss Hammurabi” for her upright views and straightforward personality, though not to the favour of her superiors.

Her zest does not end as she continues to charge ahead with her entertaining yet astute demonstrations about patriarchal behaviour. She puts her male colleagues through an experience of what would feel like sexual harassment by bringing them to the market her grandmother works at. The older ladies ogle at the two male judges, resulting in a comedic presentation of a serious issue. The arguments surrounding sexual harassment, especially in the workplace, are being dished out in their courtroom and between friends. Some may call Oh-reum a feminist for her behaviour thus far, but going beyond mere labels, the drama demonstrates the injustices of a male-dominated society and the misguided conceptions that continue to be propagated.

Oh-reum’s behaviour continues to trigger Han Se-sang’s reprimands, with his defense that the older generation might not be as malleable to new ideas and sudden upheavals. South Korea’s strict social codes that pay attention to hierarchy make Oh-reum, as a new judge, seem rude and boisterous. Yet, their squabble raises an important question as to whether equality and rights should so easily be compromised simply because of a generation’s inability to adapt. Sacrifice needs to be made regardless of a quick revolution or a slow change, but the show certainly lays the stakes at each end clear for us.

Oh-reum’s behaviour continues to trigger Han Se-sang’s reprimands, with his defense that the older generation might not be as malleable to new ideas and sudden upheavals. South Korea’s strict social codes that pay attention to hierarchy make Oh-reum, as a new judge, seem rude and boisterous. Yet, their squabble raises an important question as to whether equality and rights should so easily be compromised simply because of a generation’s inability to adapt. Sacrifice needs to be made regardless of a quick revolution or a slow change, but the show certainly lays the stakes at each end clear for us.

The show’s title is a clear reference to the Code of Hammurabi, one of the earliest and most comprehensive records of legal codes. It was carved onto a pillar and proclaimed during the reign of Babylonian king Hammurabi from 1792 to 1750 BC. Oh-reum’s newfound nickname, however, paints her as a nosy subordinate. Her good intentions to push for change in the strict hierarchical order of the court, albeit also highly patriarchal, becomes a burden to her co-workers. Unfamiliar with her workplace, her seeming idealism is, in fact, inconsiderate and demanding.

This twist is precisely what makes the drama so compelling. Society is often far more complex, with lives intertwining, and with each individual having their own burden to carry. Change is hard, but often not because nobody is pushing for it, but a limitation due to the suffering each character already has to undergo.

Oh-reum’s multiple attempts at helping the underprivileged leads her to realise the flaws in her approaches. Her goodwill must be balanced with rationality and skill. This is exactly where Im Ba-reun (played by Infinite’s L/Kim Myung-soo) comes into the picture. Ba-reun is a level-headed right-hand judge to Se-sang. He can be construed of as a complete opposite to Oh-reum, with his distaste for social interaction and distanced attitude towards life. Individualistic, he constantly questions Oh-reum’s rash decisions to protest against social injustice.

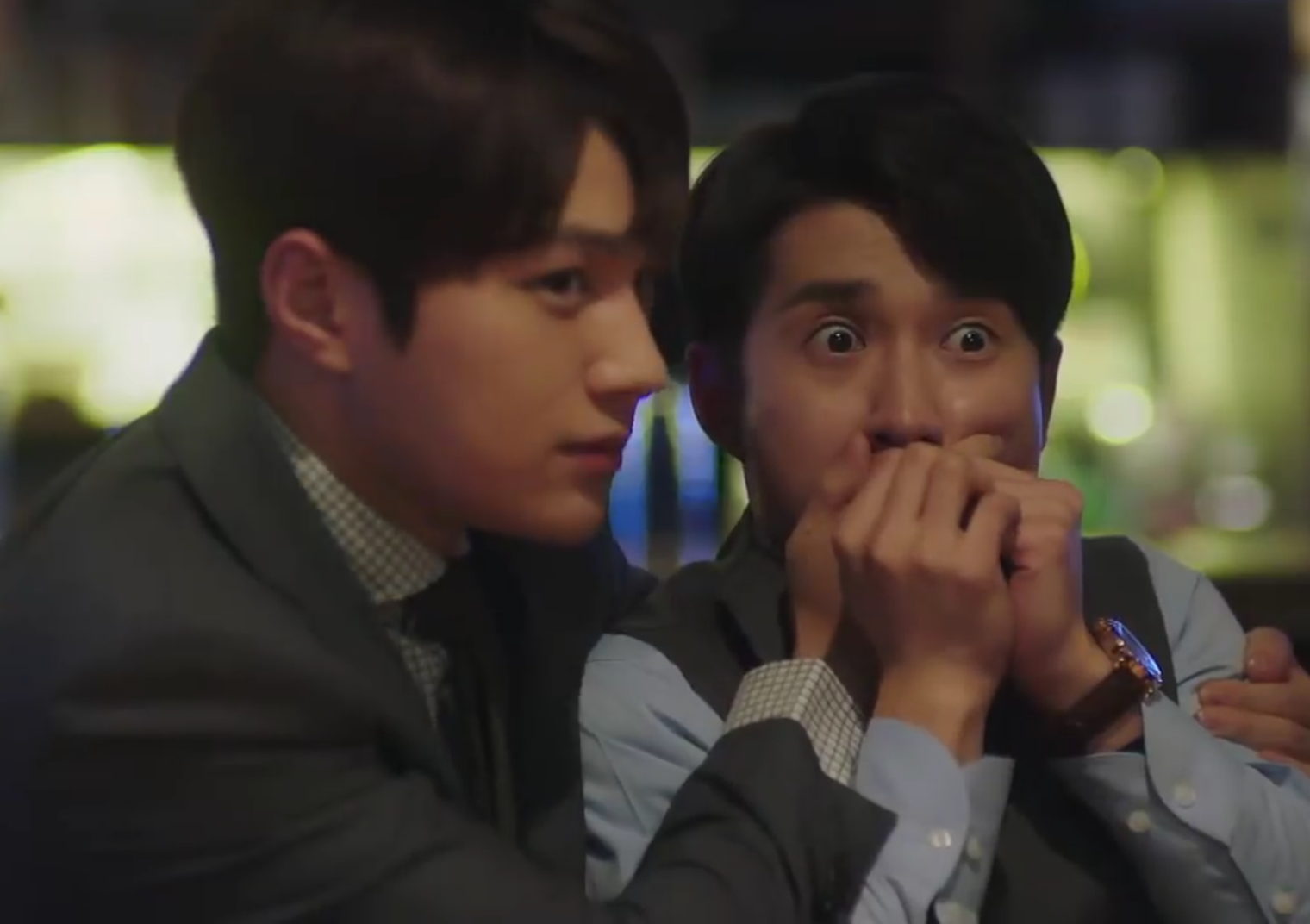

But Ba-reun’s character is more than the perfect, cool-headed, handsome judge. He struggles to support his family even in what seems to be a dignified job. Behind the glitz of the job’s title, it’s just late-nights going through case files and endless pressures coming from every direction. Even Ba-reun’s mischievous friend, judge Jung Bo-wang (played by Ryu Deok-hwan), cannot escape the suffocating atmosphere of having to flatter his superiors and participate in seemingly useless social gatherings while trying to manage an overwhelming workload. Viewers get the pathetic image of him clubbing in episode 9, with his charisma hitting rock bottom as his confession at being a judge is being brushed off as a lie.

But Ba-reun’s character is more than the perfect, cool-headed, handsome judge. He struggles to support his family even in what seems to be a dignified job. Behind the glitz of the job’s title, it’s just late-nights going through case files and endless pressures coming from every direction. Even Ba-reun’s mischievous friend, judge Jung Bo-wang (played by Ryu Deok-hwan), cannot escape the suffocating atmosphere of having to flatter his superiors and participate in seemingly useless social gatherings while trying to manage an overwhelming workload. Viewers get the pathetic image of him clubbing in episode 9, with his charisma hitting rock bottom as his confession at being a judge is being brushed off as a lie.

As the drama chugs full-steam forward, it is wonderful to watch how the characters begin to learn from each other. Ba-reun slowly adopts an approach that seeks to understand rather than pass quick judgement, much like Oh-reum. He begins to resist the establishment that demands quiet subordination at the expense of individual health and dignity. Perhaps one of the largest turning points would be the protest initiated by Oh-reum in response to the overworking of a co-worker, judge Hong Eun-ji (played by Cha Soo-yeon).

Due to the demands of her presiding judge, Eun-ji pushes herself to exhaustion despite her pregnancy. This, of course, ends badly as she suffers a miscarriage. Enraged by the entire situation, Oh-reum begins a petition. The petition divides the entire court, putting even more pressure on Ba-reun and Bo-wang who fear being deemed as troublemakers for associating with Cha Oh-reum.

Not only does this entire affair highlight the poor treatment of female workers in society, viewed as slowing down efficiency for taking maternity leaves and getting married, it spotlights the fundamental problems of a system used to burying injustices.

Not only does this entire affair highlight the poor treatment of female workers in society, viewed as slowing down efficiency for taking maternity leaves and getting married, it spotlights the fundamental problems of a system used to burying injustices.

Yet, the drama delivers another dimension of depth, remaining steadfast in presenting a diversity of perspectives. The chief presiding judge (played by Ahn Nae-sang) is an important voice of reason as he explains to Ba-reun and Oh-reum, at multiple occasions, that not everybody is as privileged to be as intelligent or as accomplished at a young age. Some are unable to graduate from well-known universities, and some have to take the bar exam multiple times to be where they are now. Even if they may appear mindlessly ambitious in their boot-licking and inhumane drive for work, they do so to stay in the race. This serves as a reminder not only to the two hot-blooded young judges but also to viewers who might be too quick to despise characters whose behaviour might seem undignified.

Another compelling aspect of the drama lies in the space it gives for building character relationships. Even though it is made known from the start that Ba-reun had a crush on Oh-reum while they were in high school, their encounter later as co-workers is not rushed into a love story. Instead, we are made privy into Oh-reum’s family dysfunction and childhood traumas of being sexually harassed. Her present situation is a drastic change from the wealthy background Ba-reun remembers, and he learns more about her together with us.

Becoming friends is hard enough for the two leads whose personalities are miles apart from each other. Even Ba-reun’s confession cannot change Oh-reum’s heart. A realistic depiction through and through—the show is more than halfway through and they are still growing as characters, colleagues, and friends.

The relationship between the two leads is not the only romantic development, though it is hard to predict the end result. Bo-wang’s crush on Lee Do-yeon (played by Lee Elijah) is equally fascinating and immensely hilarious. The eloquent judge cannot seem to keep his composure in front of the enigmatic and capable courtroom stenographer. Her secret personal life is hinted at, but nobody has any insights into the matter, not even us as viewers. As Bo-wang drives himself up a wall trying to ask her out, we are left with his amusing attempts to act nonchalant even when he is clearly infatuated.

The relationship between the two leads is not the only romantic development, though it is hard to predict the end result. Bo-wang’s crush on Lee Do-yeon (played by Lee Elijah) is equally fascinating and immensely hilarious. The eloquent judge cannot seem to keep his composure in front of the enigmatic and capable courtroom stenographer. Her secret personal life is hinted at, but nobody has any insights into the matter, not even us as viewers. As Bo-wang drives himself up a wall trying to ask her out, we are left with his amusing attempts to act nonchalant even when he is clearly infatuated.

As cases open up and close for the civil case department, we are presented with a spectrum of issues. From dealing with depression as a white-collared worker to family inheritance squabbles, public protests, as well as having to deal with political campaign issues, none of these is glossed over easily. Treating each case meticulously, the drama pays attention to the nuances of each individual involved and its eventual verdict.

Understanding is at the core of each problem, be it personal or judicial. Trying to wrap up an issue without first considering the true reason behind each action is efficient, but it is an approach that is ultimately irresponsible. The three judges grow to learn the importance of listening to another’s story and digging deeper to better understand each situation. Even Se-sang learns to look at things from the perspectives of his younger subordinates.

The story thus far has opened many threads and continues to layer itself with entrances from characters like Oh-reum’s childhood family friend, Min Yong-joon (played by Lee Tae-sung). A stunning chaebol character that is the Head of General Affairs at his father’s company – would he end up as a love rival? Seems unlikely at the moment from Oh-reum’s deliberate distancing from him, but who is to say what might happen next. It is almost impossible to predict what might happen as new cases continue piling onto the three judges.

The story thus far has opened many threads and continues to layer itself with entrances from characters like Oh-reum’s childhood family friend, Min Yong-joon (played by Lee Tae-sung). A stunning chaebol character that is the Head of General Affairs at his father’s company – would he end up as a love rival? Seems unlikely at the moment from Oh-reum’s deliberate distancing from him, but who is to say what might happen next. It is almost impossible to predict what might happen as new cases continue piling onto the three judges.

Not exactly a drama packed with thrill typical of courtroom dramas, Miss Hammurabi is instead heartwarming in each anecdote it delivers. It is comforting to watch, yet at the same time intellectual in the issues it chooses to address. Perhaps it is the script writer’s own occupation that leads to the nuance behind its story. The anticipation that comes with watching Miss Hammurabi is certainly different from that of other dramas. Rather than eagerly wanting to find out who ends up with who in the end, it is the critical engagement of pertinent societal issues, that is truly worth looking forward to each week.

(History, The Korea Herald, YouTube. Images via JTBC)