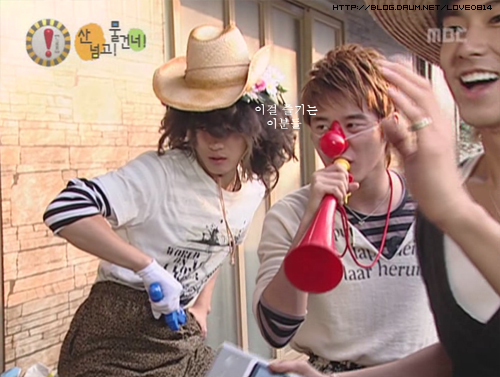

A whole bunch of new variety shows have been cropping up on the K-pop scene lately — which is great news for me because I’d take an embarrassing-but-hilarious variety show over seven hundred Music Bank “specials” any day. I’m not really sure when it happened, but the K-pop of today seems a hell of a lot more serious than the days when I started getting into K-pop…you know, back when DBSK dressed up like this purely for the entertainment of the public:

Hard to remember a time when K-pop wasn’t always a serious affair, right?

It’s a pity that K-pop culture has become so oversaturated with idols, especially considering that the larger Korean entertainment scene also hosts a good crowd of comedians — many of whom were active and popular long before some of today’s idols were even born. There was a time when idols seldom appeared on television unless they were accompanied by a host of gagmen who were there to bring out the idols’ stupid, silly sides. Now, the K-pop landscape is defined primarily by live performances and “Hallyu,” leaving little room for comedians to interact with idols and cultivate the silliness that used to help diffuse the suffocating seriousness of an idol’s pristine image.

But even as the comedy scene becomes increasingly detached from idol television appearances, there is one group of comedians that remains a prominent part of the K-idol scene: female comedians, or gagwomen. Many followers of K-pop boy groups will be familiar with names such as Jung Ju-ri, Shin Bong-sun, Park Kyung-lim, and Kim Shin-young — and even if these names don’t immediately ring a bell, most K-pop fans have probably encountered some iteration of the classically unattractive, middle-aged, man-eating gagwoman-turned-ahjumma-fan, usually seen in hot pursuit of a young, attractive male idol. The actions and personalities of these gagwomen are always played up for laughs — male comedians make candid remarks on the gagwoman’s age, physical appearance, and distastefully unsubtle attitudes, while the young male idols try to fend off the gagwoman’s pretend advances as politely as they can.

In a way, one can’t help but feel a bit of pity for these gagwomen. Of course, the personalities and behaviors that these gagwomen portray are nothing more than characters created simply for the sake of entertainment, but when your entire career is practically defined by a character that is constantly regarded as old, fat, and unattractive, it’s gotta hurt at least a little — especially considering that, in the eyes of television viewers, these characters are practically synonymous with the comedians that play them.

In a way, one can’t help but feel a bit of pity for these gagwomen. Of course, the personalities and behaviors that these gagwomen portray are nothing more than characters created simply for the sake of entertainment, but when your entire career is practically defined by a character that is constantly regarded as old, fat, and unattractive, it’s gotta hurt at least a little — especially considering that, in the eyes of television viewers, these characters are practically synonymous with the comedians that play them.

The portrayal and treatment of gagwomen on Korean variety shows merits a serious discussion on gender dynamics and sexism. After all, gagmen are not nearly ridiculed for their appearances, age, or even their affinity for female idol stars as much as gagwomen are, and the fact that gagwomen are constantly disparaged for their age, physical appearance, or forward attitude — traits emphasizing the fact that gagwomen do not (or cannot) adhere to gender norms and expectations — makes for yet another blatant and damning indicator of sexism within Korean entertainment. After all, the Korean entertainment industry is one that has long been defined by its strict adherence to a gender binary and gender stereotypes, and it doesn’t hesitate to in punishing those who step out of line. Korean gagwomen are certainly no exception to the rule.

That said, however, one might question why Korean female comedians — women who make absolutely no pains to stick to gender expectations — still manage to maintain such a prominent and important presence in Korean entertainment. While it’s true that gagwomen suffer what essentially constitutes as verbal abuse from variety show hosts, gagmen, and even idols, this image of the beleagured gagwoman really only exists so long as one chooses to view them as such. In reality, gagwomen play a major part in maintaining and directing the flow and direction of variety shows and the people who appear in them. As show hosts and facilitators of conversation, gagwomen hold a lot of power.

While their portrayal on television tends to paint gagwomen as nothing more than silly, uninhibited funnypeople, in reality gagwomen are still on the job during their appearances on variety shows — and, like any other job, they are held to a set of responsibilities and duties that they must fulfill. These responsibilities are quite simple: 1) facilitate the flow and direction of the show, and 2) be funny. But as straightforward as these responsibilities might seem, they require that gagwomen stretch the limits of gender stereotypes and pursue a kind of leadership and control that is usually reserved for men.

Deborah Tannen’s bestselling book You Just Don’t Understand made a big splash on general audiences as well as the academic community when it was released in the early 1990s. It was one of the first books on gender and linguistics targeted towards a lay audience, and was particularly controversial in its assertion that language usage was directly correlated to biological sex, in that males speak using “men’s language” while females use “women’s language.” The former is characterized as being assertive, direct, and crude, while the latter is more passive, indirect, and polite. These conclusions were drawn from observations noting that most men in a given research sample tended to speak assertively, while most women tended to be more deferential in their speech. General audiences raved over the book, citing it as the perfect antidote for doomed marriages and other instances of male-female miscommunication. Many academics, however, were facepalming in horror at Tannen’s theory that one’s usage of language could be determined solely by one’s biological sex, with little regard to external factors.

Deborah Tannen’s bestselling book You Just Don’t Understand made a big splash on general audiences as well as the academic community when it was released in the early 1990s. It was one of the first books on gender and linguistics targeted towards a lay audience, and was particularly controversial in its assertion that language usage was directly correlated to biological sex, in that males speak using “men’s language” while females use “women’s language.” The former is characterized as being assertive, direct, and crude, while the latter is more passive, indirect, and polite. These conclusions were drawn from observations noting that most men in a given research sample tended to speak assertively, while most women tended to be more deferential in their speech. General audiences raved over the book, citing it as the perfect antidote for doomed marriages and other instances of male-female miscommunication. Many academics, however, were facepalming in horror at Tannen’s theory that one’s usage of language could be determined solely by one’s biological sex, with little regard to external factors.

Current scholarship on gender and sociolinguistics has determined that the disparity between “men’s language” and “women’s language” has less to do with biological sex and more to do with power balances across the gender spectrum. However, Tannen’s now-outdated research still presents two important conclusions: one; that language can be roughly dichotomized into “powerful” and “powerless” characteristics (which Tannen mis-identifies as “men’s” and “women’s” language), and two; that stereotypes regarding “male” and “female” speech and behavior can easily be supported by social affirmation, primarily through the reinforcement of gender roles and stereotypes (i.e. men are “expected” to be straightforward; women are “expected” to be polite, etc).

In other words, there exists two types of language, and while the usage of one type of language over another depends primarily on power dynamics, the combined effects of gender stereotypes as well as the presence of male privilege and power creates a general social trend in which men are expected to adopt “powerful” language, while women are expected to utilize “powerless” language. However, these are expectations, not rules — men don’t always utilize powerful language, and women don’t always utilize powerless language.

So what does all of this have to do with Korean gagwomen? A look at the two aforementioned responsibilities of gagwomen — facilitating conversation and being funny — makes it clear that gagwomen can’t fulfill the basic tenets of their jobs unless they use the kind of assertive and direct language that is usually classified as “men’s language.” Facilitating discussion amongst multiple participants requires one to be direct and intentional with one’s speech, and the blunt, snappy nature of Korean comedy almost makes it almost impossible for a gagwoman to be funny if she has to be polite and deferential all the time.

So what does all of this have to do with Korean gagwomen? A look at the two aforementioned responsibilities of gagwomen — facilitating conversation and being funny — makes it clear that gagwomen can’t fulfill the basic tenets of their jobs unless they use the kind of assertive and direct language that is usually classified as “men’s language.” Facilitating discussion amongst multiple participants requires one to be direct and intentional with one’s speech, and the blunt, snappy nature of Korean comedy almost makes it almost impossible for a gagwoman to be funny if she has to be polite and deferential all the time.

In other words, gagwomen essentially adopt “male” speech and behavior when they appear on variety shows — not necessarily because they want to break any gender stereotypes, but simply because they need to in order to do their jobs. However, by adopting and practicing powerful male speech and behavior, gagwomen also gain and exercise power — the same power that led Tannen to mistakenly identify “powerful” speech as “male” speech. This power is needed in order for gagwomen to fulfill the duties of their jobs, but it also shakes certain foundational and cultural values regarding male privilege and female social powerlessness.

Take, for instance, the clip below from Oh! My School in which Park Kyung-lim takes on the role of the main host while Kim Shin-young is a guest or secondary host. Park Kyung-lim takes direct command of the show’s dialogue — she frequently asks pointed, blunt questions and addresses the show participants in a direct manner. Kim Shin-young, on the other hand, speaks in a very aggressive and forward manner to Tony An, and also has no qualms in expressing her “affinity” for Jinwoon, an attractive male idol assumed to be “too good” for Kim Shin-young. Nevertheless, Kim Shin-young speaks and acts boldly in reference to her “crush” on Jinwoon — a marked contrast to the female guests on the show who don’t do much apart from sitting back and giggling:

But if gagwomen are so empowered, why are they constantly disrespected and ridiculed by their fellow male comedians? In the clip above, Park Myung-soo teases Kim Shin-young about her “XL” sized sweater even though the sweater has absolutely nothing to do with the scenario at hand. This is a common trope in Korean variety shows — jokes directed at gagwomen are random and make little sense within the context of the current situation, but are nonetheless seen as “zingers” and a sign of the gagman’s ingenuity and sense of humor.

The fact that gagmen treat gagwomen in a starkly more aggressive manner than they would any other female guest on a variety show is perhaps an indicator of retaliation against a dramatic shift in power, in which the male position of social power is challenged by gagwomen — who, while still women, nonetheless speak and act in a masculinized manner, thus claiming a kind of power that is usually only held by men. Whenever there is a shift in power, the previous holder of power — in this case, men — might feel threatened and find the need to retaliate.

In the context of Korean variety shows, this oftentimes takes the form of disparaging remarks against a gagwoman’s age or unfeminine appearance. It’s particularly interesting to note that gagmen almost always make fun of a gagwoman’s femininity or lack thereof. It’s a cheap shot, but it makes sense considering that gagwomen are essentially operating on an equal plane as gagmen, and that the only thing that a gagman can still hold over a gagwoman’s head is her lack of femininity and the fact that she does not align to gender expectations. In the end, the ridiculing of gagwomen by gagmen is quite childish — it boils down to the classic trope of making fun of people who don’t fit in with social expectations. Furthermore, it also indicates a scenario in which male privilege and power are being challenged by gender-bending women — however unintentionally — and men are responding aggressively to this challenge.

Most importantly, it is the gagwomen who instigate this power struggle; they are the ones provoking the men and challenging their power. The men’s actions, then, are purely defensive. In that sense, gagwomen shouldn’t be victimized for being “bullied” by gagmen who say mean things about their age, weight, physical appearance, or lack of refinement. Gagwomen are powerful; their career places them in a position where they are given an enormous amount of control and are allowed to act and speak in a manner uninhibited by the pressures of maintaining “feminine graces.” Moreover, it is this same power that allows them to challenge male privilege and begin a power struggle in the first place.

Most importantly, it is the gagwomen who instigate this power struggle; they are the ones provoking the men and challenging their power. The men’s actions, then, are purely defensive. In that sense, gagwomen shouldn’t be victimized for being “bullied” by gagmen who say mean things about their age, weight, physical appearance, or lack of refinement. Gagwomen are powerful; their career places them in a position where they are given an enormous amount of control and are allowed to act and speak in a manner uninhibited by the pressures of maintaining “feminine graces.” Moreover, it is this same power that allows them to challenge male privilege and begin a power struggle in the first place.

However, the one thing that is keeping gagwomen from being Champions of Feminism within the Korean entertainment world is the fact that gagwomen aren’t intentionally challenging gender norms, but simply do so “by accident” through their jobs as entertainers and variety show hosts. Thus, one could argue that this discussion about the “power” of gagwomen is hardly viable because the granting of power to gagwomen is not done as a means of intentionally equalizing the power balance between men and women. There is no greater, purposeful, and intentional feminist cause behind this phenomenon; thus, little progress is actually made towards promoting female empowerment. And at the end of the day, gagwomen are still ridiculed (though not necessarily oppressed) by gagmen for not aligning with gender expectations and stereotypes. The fact still stands that while a gagwoman can execute a brilliant comedic dialogue using direct, powerful, “manly” speech and take full control of an entire conversation, she can still be immediately shot down by a gagman making a random joke about her weight or her age.

These arguments are perfectly valid, and yes — at this point it’s not yet fair to say that gagwomen are harbingers of feminism or champions of gender equality. However, one thing is for sure: the intersection of sexism and Korean comedy is very complex and cannot simply be defined by the simple assertion that gagwomen are “oppressed” because they are bullied by gagmen for their lack of feminine graces.

This isn’t a problem concerning Korean culture as much as it is a problem concerning sexism and gender stereotypes on a global scale. It’s easy to look at the plight of Korean gagwomen and the sexist attitudes that they must endure and simply regard it as yet another instance of Korean Sexism® without really considering its own unique challenges. While it is true that sexism is at play here to a certain degree, it is evident that the situation surrounding Korean gagwomen is far more complicated than one might think. The same applies to other situations in K-pop that we might otherwise simply write off as a product of Korea’s inbred sexist values. The assumption that Korea is an inherently sexist and racist country is a brash one, but it’s an assumption that is continually increasing in popularity — to the point where many seem unwilling to explore the reasons why something in K-pop is sexist or racist (if it really is at all), and are more comfortable with the blanket assumption that something is sexist or racist simply because it just is (or worse, because it is Korean.)

This isn’t a problem concerning Korean culture as much as it is a problem concerning sexism and gender stereotypes on a global scale. It’s easy to look at the plight of Korean gagwomen and the sexist attitudes that they must endure and simply regard it as yet another instance of Korean Sexism® without really considering its own unique challenges. While it is true that sexism is at play here to a certain degree, it is evident that the situation surrounding Korean gagwomen is far more complicated than one might think. The same applies to other situations in K-pop that we might otherwise simply write off as a product of Korea’s inbred sexist values. The assumption that Korea is an inherently sexist and racist country is a brash one, but it’s an assumption that is continually increasing in popularity — to the point where many seem unwilling to explore the reasons why something in K-pop is sexist or racist (if it really is at all), and are more comfortable with the blanket assumption that something is sexist or racist simply because it just is (or worse, because it is Korean.)

One could interpret the verbal abuse of Korean gagwomen simply as a side effect of Korea’s supposed ingrained sexism, or one could look deeper and see that the power struggle between men and gender-bending women is certainly not unique to Korea and holds striking similarities to female politicians running in male-dominated electoral races or businesswomen trying to climb up the corporate ladder within a male-dominated business world. Just like female politicians or businesswomen, Korean gagwomen are empowered people that are putting up a good fight in spite of a global society that still honors male privilege.

Korean gagwomen are subtle rulebreakers who exercise their power in ways that oftentimes go undetected. By refusing to acknowledge the complex relationship between gagwomen and patriarchy, and by dismissing the gagwoman as simply another victim of Korean Sexism®, then, one would also be dismissing the fact that Korean gagwomen are playing an important role in questioning the validity and integrity of the gender stereotypes and expectations — an issue that is relevant not just to Korea, but to the global community at large.

(Youtube [1], Deborah Tannen, You Just Don’t Understand (New York: William Morrow & Company, Inc., 1990); images via MBC, DCNews, JoyNews24, SPN, LovelyFocus)