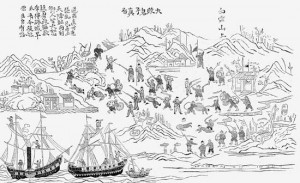

The 19th century marked the period of the Opium Wars which opened the Chinese market to imperialist powers through sheer acts of brute force. The 21st century bears witness to another effort to enter the lush Chinese market through the global reach of the K-pop industry. This time around the tactics are certainly less coercive but the ambition remains as vigorous as ever. Like their counterparts from the imperialist age, the powers that run K-pop are doing everything they can to conquer the highest potential market outside of the US. What’s their latest strategy? Go native.

The 19th century marked the period of the Opium Wars which opened the Chinese market to imperialist powers through sheer acts of brute force. The 21st century bears witness to another effort to enter the lush Chinese market through the global reach of the K-pop industry. This time around the tactics are certainly less coercive but the ambition remains as vigorous as ever. Like their counterparts from the imperialist age, the powers that run K-pop are doing everything they can to conquer the highest potential market outside of the US. What’s their latest strategy? Go native.

CJ E&M is part of a large Korean conglomerate of corporations, known as CJ Group, which controls businesses in multiple industries from food service to entertainment. Its music division is run through Mnet Media, whose subsidiary agencies and media outlet focus on promoting K-pop on an international scale. CJ E&M is collaborating with a Chinese entertainment agency, Super Jet Entertainment, in creating the six-member boy band, TimeZ. In an unprecedented move, the group released its debut single, “Hurray for Idols,” exclusively in Chinese and promoted it on Mnet’s music show, M! Countdown. The group’s dynamic reveals a culmination and progression of the strategies that have been put into play in the quest for China. Before jumping into why TimeZ is such an evolved creature, let’s survey past efforts that Korean entertainment agencies have utilized in their attempt to secure a spot for themselves in the unfamiliar industry of Chinese pop music, otherwise known as C-pop.

Starting with the group that put in a most lackluster attempt in promoting their “One Asia” project, Orange Caramel’s efforts to reach out to Chinese audiences were rather bleak. They hinted at an endeavor into the Chinese market by covering a popular Chinese cover of M2M’s “The Day You Went Away,” and releasing it on the Taiwanese version of their first mini-album. However, their foreshadowing of more Chinese releases to come never came to fruition as their only attempt to appeal to a Chinese audience afterwards was the culture vulture release that was “Shanghai Romance.”

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-kQuGejJCcU&w=420&h=315]Perhaps one of Orange Caramel’s shortcomings in appealing to a Chinese audience is that they lack any ethnically Chinese or Chinese-speaking members. F(x) has the blessing of two ethnically Chinese members though only Victoria is lauded for her ability to speak in China’s promotional language, Mandarin. Their spirited, half-Chinese, half-Korean, and part English cover of Teresa Teng’s classic song “Tian Mi Mi” during Music Bank’s Hong Kong appearance was a much appreciated tribute, but nevertheless it didn’t do much towards furthering K-pop into the Chinese market.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4zR9ilBRTNE&w=560&h=315]Miss A has the benefit of having two Chinese nationals in their quartet and though they were initially marketed as the “Chinese Wonder Girls,” their visions of taking the C-pop market by storm has fallen well short. Their strategy follows the template for promoting in Japan in which their Korean hits are remade by replacing the Korean lyrics with Chinese ones. This promotional strategy embodies the assumption that a hit song at home will naturally translate into a breakthrough hit in another country. While this theory does occasionally work in Japan with groups like Kara and Girls Generation, the logic is highly flawed as big acts like 2NE1 and T-ara have realized less than worthy outcomes in their Japan ventures. To their credit, miss A is the only group that is consistently applying this strategy the Chinese market. However, the futility of this plan is that there is a linguistic barrier in the Chinese language which detracts Chinese-speaking audiences from the appeal of a song that has been conveniently translated into their national language. This factor will be touched upon later. Although the Chinese version of their current hit “I Don’t Need a Man” is actually quite audibly bearable, their most linguistically-appeasing Chinese-version song is surprisingly a CF track for Samsung, “Love Again.”

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9JBq45FKfvk&w=420&h=315]The hands-down industry leader in the assault on China is SM Entertainment, earned through the success of the sub-unit Super Junior-M. Super Junior-M was formed by partitioning five members from the main Super Junior lineup and the addition of two new members, making the initial group of seven consist of three ethnically Chinese members. After Han Geng‘s departure from Super Junior, the addition of two more members from the main lineup made the current roster consist of three Chinese members in what is now an eight-member group. Super Junior-M made a strong debut with a Chinese version of their Korean hit, “U.” Their first album consisted mostly of Korean remakes and Chinese covers, one of which is the delightful “At Least There’s Still You,” which they promoted alongside “U” and used to show off the group’s strong vocal abilities, an essential component of success in the Chinese market.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eQLbcBOkX6s&w=420&h=315]After “U,” Super Junior-M changed their strategy a bit. Instead of remaking their smash hit “Sorry, Sorry” for a Chinese audience, they created a separate song in Chinese which fell in line with much of the musical stylings of “Sorry Sorry.” “Super Girl” was the outcome and it resulted in further accolades for the group. As an eight member band, they stuck to the same formula and released “Perfection.” These two releases display the electro-synth sound and synchronized dancing that Super Junior (and much of K-pop) is known for. They’ve also relied less on covers and more on original compositions and collaborations with Chinese producers in their music. As a result, Super Junior and Super Junior-M alike have gained much popularity in Taiwan but still fell short in their main target market, China. Perhaps SJM would have fared better in the Chinese motherland had they promoted “Love is Sweet,” a song which is more familiar to the sound of the genre because it was produced by C-pop megastar singer and producer Jay Chou and his lyricist sidekick Vincent Fang.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2nkqV09l6kI&w=420&h=315]Following on the success of Super Junior and Super Junior-M, SM formed Exo, which is split into Exo-M and Exo-K, two autonomous groups with their own separate set of members who promote the same songs in the language of their respective markets. Exo’s Chinese unit, Exo-M, consists of six members, four of which are Chinese. Every Exo-K release so far has been accompanied by an Exo-M release of the same song and MV in Chinese. The benefit of this innovative approach is that it allows Exo to promote simultaneously in Korea and China. The obvious pitfall is that this merely combines the marketing strategies of miss A with that of SJM. Their Chinese releases are decrepit translations of songs that were originally designed to be in Korean. Deploying Chinese members to perform these songs do not make them any less of a turn off to the Chinese speaker’s linguistic-auditory senses. It’s no surprise that the Chinese versions of their upbeat electronic hits “History” and “Mama” are inferior by comparison to their more ear-pleasing Chinese song, “What is Love,” because it shows off their vocals and closely conforms to the conventional slow jam RnB and ballad styles of C-pop.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7PMRe4k3OSw&w=560&h=315] The driving force behind SM’s thrust into the Chinese market is their founder Lee Soo-man and what he’s labeled as “cultural technology.” Derived from the term “information technology,” Lee thinks of cultural technology as a system designed to replicate a pop culture which has the ability to transcend national, ethnic, and cultural boundaries. Through SM’s sacred manual of cultural technology, which supposedly documents a step by step process on how to spread K-pop across Asia, it holds a competitive edge in exporting their products across national borders. Japan and Taiwan have largely been consumed by the likes of their two staple groups, Super Junior and Girls Generation. While SM’s first generation groups H.O.T and S.E.S made some headway into China, the enormous potential of the Chinese market has remained largely untapped by any K-pop act. The China roadblock is what SM is attempting to hurdle with Exo-M, but in order to do so it must undergo a paradigm shift regarding their understanding of C-pop.

The driving force behind SM’s thrust into the Chinese market is their founder Lee Soo-man and what he’s labeled as “cultural technology.” Derived from the term “information technology,” Lee thinks of cultural technology as a system designed to replicate a pop culture which has the ability to transcend national, ethnic, and cultural boundaries. Through SM’s sacred manual of cultural technology, which supposedly documents a step by step process on how to spread K-pop across Asia, it holds a competitive edge in exporting their products across national borders. Japan and Taiwan have largely been consumed by the likes of their two staple groups, Super Junior and Girls Generation. While SM’s first generation groups H.O.T and S.E.S made some headway into China, the enormous potential of the Chinese market has remained largely untapped by any K-pop act. The China roadblock is what SM is attempting to hurdle with Exo-M, but in order to do so it must undergo a paradigm shift regarding their understanding of C-pop.

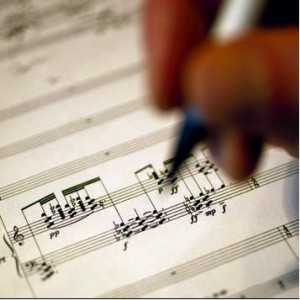

C-pop is very different from K-pop not only because it tends to favor a narrower selection of genres, but also because of the restrictions put on it by the principles of the Chinese language. Chinese, regardless of the dialect, is a tone-based language. This means that there are many words which share the same sounds and are only differentiated by the tone through which it is assigned. It is this combination of sound and tone which bestows words with meaning. Given that Mandarin only consists of four main tones and only a few select choices of sounds, it becomes highly unintelligible if the tones spoken are ignored or projected incorrectly, a huge problem amongst non-native Chinese language learners in their early stages.

The main problem that plagues C-pop is how it must create music to fit a language in which the tone of the words need to match the exact tone of the melody in order for the lyrics to be intelligible. In Canto-pop — a sub-genre of C-pop in which Cantonese is used as the primary language — Cantonese’s higher variation of tones allows every lyric to match very closely to the tone of the melody, making the lyrics mostly intelligible. Even so, producers are burdened with the crafty task of having to use highly irregular word choice in appropriating the lyrics to match the desired melody, or fiddle with the melody to match the desired lyrics. Canto-pop’s unrelenting resolve to not sacrifice intelligibility in exchange for greater liberties in the melody is something which Mando-pop, the more common Mandarin-based form of C-pop, cannot afford because of Mandarin’s limited number of tones. Pop music cannot be made from only four separate tones. Therefore, Mando-pop has no choice but to trade off a certain degree of intelligibility in order to make music that is catchy and melodious, the essence of pop.

The main problem that plagues C-pop is how it must create music to fit a language in which the tone of the words need to match the exact tone of the melody in order for the lyrics to be intelligible. In Canto-pop — a sub-genre of C-pop in which Cantonese is used as the primary language — Cantonese’s higher variation of tones allows every lyric to match very closely to the tone of the melody, making the lyrics mostly intelligible. Even so, producers are burdened with the crafty task of having to use highly irregular word choice in appropriating the lyrics to match the desired melody, or fiddle with the melody to match the desired lyrics. Canto-pop’s unrelenting resolve to not sacrifice intelligibility in exchange for greater liberties in the melody is something which Mando-pop, the more common Mandarin-based form of C-pop, cannot afford because of Mandarin’s limited number of tones. Pop music cannot be made from only four separate tones. Therefore, Mando-pop has no choice but to trade off a certain degree of intelligibility in order to make music that is catchy and melodious, the essence of pop.

Nevertheless, for the sake of preserving some sense of intelligibility in their songs, producers of C-pop cannot completely ignore word tones. They must keep the lyrics in mind while composing their songs and craft the melody to somewhat suit the correct word tones. This is not always possible and composers work closely with the lyricists to find a fitting compromise. Even with such lyric-focused composition at work, it’s important to note that the lyrics of C-pop, and particularly Mando-pop, are at times even unintelligible to the native Chinese speaker because of their non-accommodating tones, and thus captions are required at all times on a C-pop MV in order for the lyrics to be fully comprehensible. It’s for this reason that the genre favors slow-paced songs over upbeat dance tracks – the quicker the lyrics are sung, the harder they are for the audience to take in and to understand.

Nevertheless, for the sake of preserving some sense of intelligibility in their songs, producers of C-pop cannot completely ignore word tones. They must keep the lyrics in mind while composing their songs and craft the melody to somewhat suit the correct word tones. This is not always possible and composers work closely with the lyricists to find a fitting compromise. Even with such lyric-focused composition at work, it’s important to note that the lyrics of C-pop, and particularly Mando-pop, are at times even unintelligible to the native Chinese speaker because of their non-accommodating tones, and thus captions are required at all times on a C-pop MV in order for the lyrics to be fully comprehensible. It’s for this reason that the genre favors slow-paced songs over upbeat dance tracks – the quicker the lyrics are sung, the harder they are for the audience to take in and to understand.

It is with this advanced contextual understanding of C-pop that we will assess the newest product of cultural technology, TimeZ. To the untrained eye (and ear), they might not seem all that significant at first. They have the members. Like Exo-M, four of the six members are of Chinese origin. They have the moves. They have the sex appeal. But what do they have that is unlike anything else before? If you have yet to do so, check out “Hurray for Idols” before proceeding.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wTPrjKVJTzI&w=560&h=315] If Chad Future is allowed to classify his music as American K-pop, then “Hurray for Idols” should be categorized as Chinese K-pop. First of all, the Chinese lyrics are highly intelligible! Even without Chinese captions, there are many parts in which the tone of the melody match the tone of the lyrics just well and long enough to convey the correct meaning. The producers unquestionably composed the song with the Chinese lyrics in mind, most likely thanks to the folks at Super Jet Entertainment. Secondly, the song is almost entirely in Chinese. It does not rely on out of place English words or phrases to act as lyrical placeholders, further evidence that the song underwent lyric-focused composition. And most importantly, the song sounds inexplicably similar to C-pop. Yes, it also contains a lot of K-pop elements, but the sound of C-pop can be readily distinguished through the music and the melody. “Hurray for Idols” represents an ideal merger between the musical elements of K-pop and C-pop, and while TimeZ is being promoted as a part of K-pop, they might be the leap in cultural technology which will transcend the need for national or linguistic labels.

If Chad Future is allowed to classify his music as American K-pop, then “Hurray for Idols” should be categorized as Chinese K-pop. First of all, the Chinese lyrics are highly intelligible! Even without Chinese captions, there are many parts in which the tone of the melody match the tone of the lyrics just well and long enough to convey the correct meaning. The producers unquestionably composed the song with the Chinese lyrics in mind, most likely thanks to the folks at Super Jet Entertainment. Secondly, the song is almost entirely in Chinese. It does not rely on out of place English words or phrases to act as lyrical placeholders, further evidence that the song underwent lyric-focused composition. And most importantly, the song sounds inexplicably similar to C-pop. Yes, it also contains a lot of K-pop elements, but the sound of C-pop can be readily distinguished through the music and the melody. “Hurray for Idols” represents an ideal merger between the musical elements of K-pop and C-pop, and while TimeZ is being promoted as a part of K-pop, they might be the leap in cultural technology which will transcend the need for national or linguistic labels.

The parties involved understand what is at stake here. A more precise translation of the TimeZ’s debut song is “long live idols.” Like the British imperialists who bullied their way into dictating trade with China in the 18th century, today’s K-pop imperialists are looking to secure their hold on the Chinese market for many years to come. Will China get hooked on TimeZ?

And in case you haven’t noticed, this article contains a heavy sampling of my most bearable favorite Chinese language K-pop songs. What are some of yours? Let us know in the comments below!

(The New Yorker, CJ E&M Music, Lollimi Lee, hfxmania, missA, rhinodynasty, RainingPurpleLUV, SMTOWN, Super Jet Entertainment, Encylopaedia Brittanica, Newsen, Sony Music Taiwan)