Sex sells big time, everywhere and everything. You’ve got a product on the market? Just find an ‘insert alphabet letter’ line girl or a chocolate-abs guy and your job is mostly done. Hot guys and girls sell cars and phones. And then, for any other product – vinegar, shopping malls, music – there is a way to sexify it.

K-pop is no different. Being an industry that focuses mainly on image, it is objectifying at its core. An impressive number of artists out there rely on their sex-appeal to sell songs, be it under the aegyo formula or opting for a more blatant approach. But, if anything until now sounds normal, there are also some contradictions that appear when talking about the way media treats sex in the Korean environment.

One of them would be the policy that idols seem to have conformed to. Despite their image being provoking, they act as if they didn’t do it. The boys’ shirts ripped off themselves. The girls weren’t aware of the length of their skirts. This avoidance of the subject is intriguing. Everybody knows there is something sexual in the video/performance, nothing wrong with that. But the stubbornness with which they tend to dodge the bullet is impressive. Core Contents Media was very vocal in their refusal to let Gangkiz to model for lingerie because it would have damaged their image. This begs the question: why?

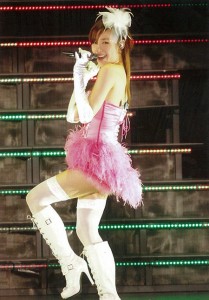

Granted, South Korea is somewhat conservative and sex is probably taboo. Also, it is not obligatory to talk about it. The bizarreness of this, though, is not that they don’t approach the subject, but that they seem to be confronted very often with sexual imagery (not Western level, but still). There is a certain degree of hypocrisy: it’s all good as long as there is not something completely explicit. If there is 1% chance that somehow, by a universal conspiracy, that scene or poster is accidentally arousing, then you can’t be accused of anything, you’re just naïve and enjoying guilt-free material. Take Tiffany as an example. Her ‘Lady Marmalade’ outfit was strongly criticized, despite most of SNSD’s and other girls groups’ outfits being as provocative. Why? The melody and the lyrics left no room for interpretation. That 1% chance wasn’t there anymore to allow people to justify her.

Granted, South Korea is somewhat conservative and sex is probably taboo. Also, it is not obligatory to talk about it. The bizarreness of this, though, is not that they don’t approach the subject, but that they seem to be confronted very often with sexual imagery (not Western level, but still). There is a certain degree of hypocrisy: it’s all good as long as there is not something completely explicit. If there is 1% chance that somehow, by a universal conspiracy, that scene or poster is accidentally arousing, then you can’t be accused of anything, you’re just naïve and enjoying guilt-free material. Take Tiffany as an example. Her ‘Lady Marmalade’ outfit was strongly criticized, despite most of SNSD’s and other girls groups’ outfits being as provocative. Why? The melody and the lyrics left no room for interpretation. That 1% chance wasn’t there anymore to allow people to justify her.

Moreover, having the music scene saturated with sex objects, it becomes incredibly annoying that they don’t ever express desire. Being sexualized is a passive role: the person has become a thing for the audience, sexually attractive, but still a thing. This process doesn’t include the idols being assertive about their sexuality: they can be wanted, but they do not want. There are some mentions of porn here and that would be it. Male idols seem to have it easier on this one, they appear as if they can explore the subject a tad more, with GD&TOP not being too prude on their album (even though it’s still about pleasing than being pleased). The common perception is that celebrities shouldn’t be associated with sex and Ivy has learned her lesson. Just the ‘news’ she had sex with her boyfriend (because otherwise, what does a sex tape mean?) was enough to degrade her.

The personas that are forced on idols also suffer from this contradiction. The aegyo (besides the already discussed implications) is all about acting like children, with the typical face expressions and infantile clothing. At the same time, they have to be as sensual as a full grown woman, displaying their femininity by showing some leg and some cleavage. Here’s UEE’s commercial:

It is spot-on: it features a dance that contains some lasciviousness, while still trying to conserve an innocent look. Although she is supposed to be exercising or expressing some actions (shaking, chewing), the sex element is there and probably ignored again.

The same thing occurs even for more daring songs, where girls don’t go for aegyo that much. Sistar‘s “How Come” was banned, initially for the content, then for the use of a pole in the video. What did the management do? State that it never crossed their mind it was sexually suggestive, and that they would adopt something more appropriate for their performances. And they’re not only ones to do this: RaNia, the defying girls that finally had both a song about sex and a sexualized image, declared they didn’t consider anything about their K-pop act to go in that direction. They were probably one of the few that got near being a sex subject, but then what did they do? Deny it and change their dance.

The male ideal in K-pop isn’t that favorable either. On one side, they have to be strong, aggressive and fearless, even nasty, when it comes to their sexual instincts. On the other side, they have to develop a sensitive side and still be untouched. They need somehow to leave the impression they can have meaningful sex, but at the same time, being promiscuous is necessary. Of course, this cliché is not fabricated in Korea, but it is largely used in dramas and videos. The flower boy isn’t that different either. While having a fragile aspect and effeminate traits, people still won’t accept it. They still need at some point for the idol to be muscular and possessive, displaying what society perceives as masculine attributes.

The male ideal in K-pop isn’t that favorable either. On one side, they have to be strong, aggressive and fearless, even nasty, when it comes to their sexual instincts. On the other side, they have to develop a sensitive side and still be untouched. They need somehow to leave the impression they can have meaningful sex, but at the same time, being promiscuous is necessary. Of course, this cliché is not fabricated in Korea, but it is largely used in dramas and videos. The flower boy isn’t that different either. While having a fragile aspect and effeminate traits, people still won’t accept it. They still need at some point for the idol to be muscular and possessive, displaying what society perceives as masculine attributes.

If we were to compare between the two, as said before, men get away with more. Undeniably, society’s perpetual Madonna-whore complex is a cause for the inequality. But men are also human and objectification is as degrading for them as it is to women. It is hard to tell if this inequality in opinions isn’t in a way more harmful for them as it is to women. Nobody says anything when they are objectified. Is this a proof of mental evolution or just a hint that the public doesn’t distinguish yet between being demeaned and expressing one’s sexuality? Undoubtedly, the double-standard in people’s reactions when it comes to women’ sexuality is unfair and should be abolished. But another problem emerges: should women aspire to be as degraded as men are in media and receive the same type of feedback? Or should this discrediting process should be eradicated for both genders?

Be it Korean society or just human awkwardness, these contradictions in how the sex topic is being addressed indicate that something is off. Maybe the outcomes presented here are not that incredibly dangerous. But shouldn’t this attitude concern the public a tad more? The problem of sex education in Korea has arisen before. In the Daegu gang rape case, the aggressors didn’t understand the harm and thought they were just imitating porn movies. Though this happens on a whole different level, it is a consequence of the same contradiction resulting from being exposed to sexual content but not being able to talk about it. Society should ensure that its members, despite not being open about sex, have a healthier view on it.

(The Grand Narrative, Korea Times, Sports Chosun, qonehomemade, Nate, Newsen)