Anime and manga has been present on U.S. television since the ’60s, but (as with a lot of things), but it wasn’t until such material became available on the internet that the profile of these proponents of Japanese culture increased. While many were happy to read, watch and leave it at that, many more end up becoming obsessed with anime and manga, with this obsession soon branching out into anything and everything Japanese. Such people were initially referred to as “Wapanese,” a portmaneau of “White” and “Japanese” (due to the fact that many of these overly obsessed fans were considered to be white people from the U.S.), but a filter on 4Chan, which attempted to prevent use of what was considered an offensive term with a nonsensical one, instead transferred all the connotations to the nonsense word: and thus the weeaboo was born.

Anime and manga has been present on U.S. television since the ’60s, but (as with a lot of things), but it wasn’t until such material became available on the internet that the profile of these proponents of Japanese culture increased. While many were happy to read, watch and leave it at that, many more end up becoming obsessed with anime and manga, with this obsession soon branching out into anything and everything Japanese. Such people were initially referred to as “Wapanese,” a portmaneau of “White” and “Japanese” (due to the fact that many of these overly obsessed fans were considered to be white people from the U.S.), but a filter on 4Chan, which attempted to prevent use of what was considered an offensive term with a nonsensical one, instead transferred all the connotations to the nonsense word: and thus the weeaboo was born.

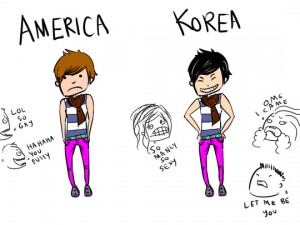

A weeaboo is typically described as someone who is not Japanese but is obsessed with Japan and Japanese culture to the point where they aspire to become as Japanese as possible. A weeaboo can, naturally, be either male or female, though the latter is more visible. Now, take the word “Japan” from the previous sentence and replace it with “Korea,” and you get the definition of a koreaboo.

Koreaboos have an intense fascination with South Korea (Korea), which compels them to take a greater interest in the country, its people and its customs. But there is one thing: the majority of a koreaboos knowledge is based on Korean pop culture in the form of K-pop, K-dramas and K-variety; and while these things do give us a glimpse into the Korean Zeitgeist, one must bear in mind that while popular culture reflects the wider issues a society faces, they are not always the best source of information. Pop culture provides commentary rather than actual content on these issues. But not seeing this difference means that many K-entertainment fans take their cues from the wrong place and treat it as the gospel truth when in fact they are sorely misinformed.

Koreaboos have an intense fascination with South Korea (Korea), which compels them to take a greater interest in the country, its people and its customs. But there is one thing: the majority of a koreaboos knowledge is based on Korean pop culture in the form of K-pop, K-dramas and K-variety; and while these things do give us a glimpse into the Korean Zeitgeist, one must bear in mind that while popular culture reflects the wider issues a society faces, they are not always the best source of information. Pop culture provides commentary rather than actual content on these issues. But not seeing this difference means that many K-entertainment fans take their cues from the wrong place and treat it as the gospel truth when in fact they are sorely misinformed.

For them, South Korea first and foremost a wonderland of hot Asian people who perform aegyo, take selcas and dress very well before they see it as a G8 nation with a large Christian population (in relation to other East Asian countries) that has just elected its first female president. One aspect of Korean culture is taken and applied to the whole country, a cruel exercise in synecdoche. These are koreaboos, and they are, understandably though harshly, looked down upon by the general populace as well as other K-pop and K-drama fans: in fact, concern over being labelled a koreaboo themselves prevents them from comfortably talking about their interest in K-pop with others.

Let’s face it, we all have, at some point, related a topic of conversation to something South Korean or Hallyu-related, tried to indoctrinate introduce others to the joys of K-pop, cooed at our oppas and unnis while seated in front of a computer screen, or even let out the occasional “omo!” whilst watching Gaksital. But koreaboos are seen to take these microexpressions and incorporate and display them in every facet of their lives.

For example, they may insist on using Korean honorific terms when addressing any Korean person they meet, often misusing said honorifics. Often, people wish to show their knowledge and respect for Korean culture, but missing out on nuances that can’t always be picked up from watching dramas means that more harm than good is caused. This also extends to use of the language as well; the use of honorifics can also be accompanied by some Korean, with the speaker varying in their level of fluency.

For example, they may insist on using Korean honorific terms when addressing any Korean person they meet, often misusing said honorifics. Often, people wish to show their knowledge and respect for Korean culture, but missing out on nuances that can’t always be picked up from watching dramas means that more harm than good is caused. This also extends to use of the language as well; the use of honorifics can also be accompanied by some Korean, with the speaker varying in their level of fluency.

Another is relating any topic of conversation back to South Korea and its pop culture. Though someone mentioning Tarantallegra may make you think of Xia rather than Harry Potter, and you may mention that fact in conversation, making a point of noting that a cover of Vogue Korea with Tiffany on the front was shown on national Australian television for less than a second might be pushing it too much. And that it what generally tends to happen with Koreaboos who have Seoul on their minds and Hallyu in their hearts.

This adoration also leads to koreaboos praising South Korea as a superior nation to others. We’ve all seen the various statements of how K-pop is much better than “trashy” American pop due to its preservation of virtuosity — which we know is not true, as both music industries include both kinds of images among many others. But the insistence that Korean is better — not based on objective analysis, but bias — is worrying, especially when this kind of behaviour is, at least subconciously, the aim of Hallyu itself — to market Korean entertainment as an attractive choice to a global audience.

This adoration also leads to koreaboos praising South Korea as a superior nation to others. We’ve all seen the various statements of how K-pop is much better than “trashy” American pop due to its preservation of virtuosity — which we know is not true, as both music industries include both kinds of images among many others. But the insistence that Korean is better — not based on objective analysis, but bias — is worrying, especially when this kind of behaviour is, at least subconciously, the aim of Hallyu itself — to market Korean entertainment as an attractive choice to a global audience.

But in the pursuit of this goal, the government-aided Hallyu movement is at risk of objectifying its own citizens. As I mentioned earlier, South Koreans may be used by koreaboos as an excuse to display their “Koreanness,” their perception of what they think it means to be Korean. which is often lacking the context that reading, studying about and living and growing up in South Korea would provide. South Koreans are often treated like prized possession, often to the point of fetishization, as though somehow being in acquaintance with a beautiful Korean somehow makes themselves Korean by association.

And this perhaps is the most dangerous notion of all, a koreaboo’s desire to become Korean. Pop culture is often an avenue of escape from the daily grind; but koreaboos buy this fantasy as reality and internalise it, resulting in this ultimate aim of becoming more Korean — because they believe being Korean is much better, more exciting and/or easier than what they are now. The thing is, though, one cannot become Korean simply by watching dramas and MVs, because that is not all there is to South Korea. As already stated, focusing on only one part of a whole is the least responsible way in which to embrace a culture.

And this perhaps is the most dangerous notion of all, a koreaboo’s desire to become Korean. Pop culture is often an avenue of escape from the daily grind; but koreaboos buy this fantasy as reality and internalise it, resulting in this ultimate aim of becoming more Korean — because they believe being Korean is much better, more exciting and/or easier than what they are now. The thing is, though, one cannot become Korean simply by watching dramas and MVs, because that is not all there is to South Korea. As already stated, focusing on only one part of a whole is the least responsible way in which to embrace a culture.

The main reason why people become koreaboos is because of ignorance; but as one comes to know more of the culture, they can grow out of what will in the future be referred to as their “koreaboo phase” and become a more conscientious consumer of Korean media. Everybody’s done something that is koreaboo-like, but we’ve also learnt from those experiences and grown. However, keeping the blinkers on and refusing to take a look sideways shuts out the experience and reason that would allow people to critically think of and analyse their behaviour sooner, rather than later (if ever). It will limit their experiences, potentially making them their own enemy.

What are your thoughts on koreaboos, readers? What have your experiences with them been like? Have you ever done something koreaboo-like?

(2008. Christian, D. J. Japanese Animation in America and its Fans. Oregon State University. memegenerator, thisisnotkorea@tumblr, thatoneasiangirl@tumblr, The Meta Picture)