A few months ago, my fellow writer Young-Ji posted about actress Kim Tae-hee‘s recent plight in Japan. To summarize briefly, Kim Tae-hee, who appeared in the Japanese drama 99 Days with a Star, came under fire for having apparently acted in support of South Korea’s claims to Dokdo, an island to which Japan also lays claim and calls Takeshima. Without exaggeration, the territorial control issue surrounding Dokdo is one of the largest sources of tension between South Korea and Japan, and Kim Tae-hee’s tacit support for South Korea in regard to Dokdo/Takeshima led to protest in October and a massive petition against her working in the Japanese entertainment industry.

A few months ago, my fellow writer Young-Ji posted about actress Kim Tae-hee‘s recent plight in Japan. To summarize briefly, Kim Tae-hee, who appeared in the Japanese drama 99 Days with a Star, came under fire for having apparently acted in support of South Korea’s claims to Dokdo, an island to which Japan also lays claim and calls Takeshima. Without exaggeration, the territorial control issue surrounding Dokdo is one of the largest sources of tension between South Korea and Japan, and Kim Tae-hee’s tacit support for South Korea in regard to Dokdo/Takeshima led to protest in October and a massive petition against her working in the Japanese entertainment industry.

Well, it apparently hasn’t gotten any better for the actress on the archipelago; earlier this week, she was forced to cancel a promotional event in connection with her new commercial endorsement of Rhoto Pharmaceutical cosmetics. The reason? Hateful netizen comments accusing her of being anti-Japanese. Though it has been four months since the initial wave of protest against her appearance in the drama (and indeed, six years since she participated in the “Love Dokdo” campaign), Japanese anger has yet to die down.

And it isn’t just Kim Tae-hee; 2PM’s Nichkhun, too, has been criticized for his most recent Thai CF, which briefly features an image of Japan’s Rising Sun flag, whose imagery has long been associated with the imperial Japanese army and its conquests and war crimes throughout Asia in the pre-World War II era. The flag is still in use by the Japanese navy today.

While Japanese netizens have been calling the CF pro-Japanese, Korean netizens have responded by accusing Nichkhun of being anti-Korean. So controversial was the commercial that it prompted JYPE to issue an official apology along with a promise to be more careful in filming and producing future CFs.

Far be it from me, or any outsider looking in to comment on the validity of sentiments on either side of the debate; the history between South Korea and Japan is long, bloody, and rife with justified grievance. Japan’s 35-year occupation of the Korean peninsula was at times horrifically oppressive, including attempts at eradicating Korean culture and language as part of a forced assimilation project undertaken alongside the Japanese war mobilization. Understandably, the numerous atrocities committed against Korea have left a bad taste in the mouths of many Koreans, and to this day there is still considerable resentment on both sides. One questions what must — or really, what can — be done to mollify the situation. The Dokdo/Takeshima dispute, which has been ongoing now for an extraordinarily long time, compounds these historical animosities.

Though cultural exchange between South Korea and Japan has been particularly robust for the past decade (and no doubt will continue to grow), it is worth remembering that (as Young-Ji put it) the very fact that Hallyu has spread to Japan with such success is nothing short of a miracle. Anti-Japanese/anti-Korean sentiment is still deeply entrenched in both societies and is often perpetuated through the education system. Though the older generation that remembers the colonial period and the Korean War is slowly starting to disappear, negative attitudes have persisted.

Though cultural exchange between South Korea and Japan has been particularly robust for the past decade (and no doubt will continue to grow), it is worth remembering that (as Young-Ji put it) the very fact that Hallyu has spread to Japan with such success is nothing short of a miracle. Anti-Japanese/anti-Korean sentiment is still deeply entrenched in both societies and is often perpetuated through the education system. Though the older generation that remembers the colonial period and the Korean War is slowly starting to disappear, negative attitudes have persisted.

Personally, I think that the reactions to both Kim Tae-hee and Nichkhun was excessive, and it seems silly to me to ruffle feathers to such a degree over something so divorced from the entertainment industry, but then again, I’m not Korean or Japanese. I have to wonder what might have happened had Kim Tae-hee been a Japanese actress working in South Korea who had supported Japan’s claim to Takeshima; I imagine that the situation would actually be far worse. It just goes to show you that as innocuous as K-pop may seem, the entertainment world can often serve as a lens through which social prejudices and discontent may be seen.

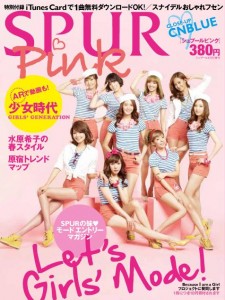

Though there are clear fissures in the relationship between South Korea and Japan, and though political and cultural resentment may still rear its ugly head from time to time, I am hopeful that the above incidents are isolated and quickly allowed to pass. Hallyu may be a largely economic enterprise, but I think that it has the potential to soften and shape the attitudes of the younger generation. Though history cannot and must not be forgotten, it would be best to remember without clinging to the pain of yesterday. I’m not exactly suggesting that Koreans and Japanese all get together in a circle and sing kumbaya (although maybe they could sing a song off of SNSD‘s Japanese album?), but finding common ground through the mutual flow of popular culture across the East Sea could do wonders for perceptions of each other on both sides, if only it is allowed to take place.

What do you say, readers? Can Hallyu help to overcome historical animosity, or do the above incidents serve only to prove the futility of the effort?

(Mark E. Caprio, Japanese Assimilation Policies in Colonial Korea: 1910-1945 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2009))