It seems that recently K-pop has been setting its sights on expanding out of Asia and towards the West.

It seems that recently K-pop has been setting its sights on expanding out of Asia and towards the West.

This past year has shown us a variety of appearances of K-pop stars in places all around the globe, from holding concerts in Europe and America, to taking part in judging MBC’s K-pop Cover Dance Festival Road Show 40120 (Miss A in LA, B2ST in Spain, SHINee in Moscow, 2PM in Thailand, KARA in Japan, and MBLAQ in Brazil). Fans all over the globe have been responding to companies’ efforts to reach out by demonstrating their fervor for K-pop in all outlets possible. This summer seemed like a string of never-ending K-pop dance flash mobs, with international fans requesting for concerts in places including but not limited to: Houston, Winnipeg, London, Dublin, Sydney, Brisbane, Munich, Kiev, Rio de Janeiro, and Peru.

In addition to globalization on the audience front, the number of instances of behind-the-scenes collaborations has also been on the rise. These days, news of K-pop acts working with famous Western producers (Teddy Riley, Eliot Kennedy, Darkchild, The Underdogs) and choreographers (Shaun Evaristo, Lyle Beniga, Keone Madrid, Mariel Martin) no longer seem surprising to any of us. Season 2 of 2NE1 TV shows footage of the girls travelling to LA and London to collaborate with Black Eyed Peas’ Will.i.am on a number of (unreleased) English tracks. Earlier this month, YG signed an agreement with American rapper Ludacris for a future collaboration in Korea. The Wonder Girls are currently filming for their upcoming Teen Nick movie, Wonder Girls at the Apollo, and are set to begin their American promotions in December. And in most recent news, the reason for the delay of SNSD’s upcoming album, The Boys, is attributed to preparations for a simultaneous album release in both Korea and US/UK (the latter will only be digital release, but the songs will be in English).

But wait, hasn’t this movement towards the West been tried before? What about the previous response to the Wonder Girls, BoA, and Se7en’s failed (despite glorification in the Korean media) attempts to effectively break into the US market? Weren’t those results an indication that we weren’t ready for K-pop into the mainstream yet? Why are Korean companies so confident about their ventures now, as opposed to a few years ago? Has the atmosphere changed? Is the mainstream audience in the US now ready accept a good dose of K-pop?

Personally, I don’t believe so, nor do I believe it will ever happen… unless it is promoted as American music and not as K-pop (but at that point I don’t think it counts as being part of the Hallyu wave). But the thing is – I don’t think Korean companies are necessarily targeting the true mainstream like they tried to in the past. What they are doing this time around is targeting an already existing non-mainstream niche market and trying to work from there. They don’t need to secure new fans when they’ve already got legions of non-mainstream consumers patiently waiting for them to come to their home countries. They can still make a ton of money off these devoted fans, who would probably be more than willing to help manipulate album or digital sales to get positions on music charts (a TERRIBLE and unethical practice, by the way) so that our favorite K-pop groups can march on home with their heads held high and brag about how they took over America. But in reality, will an American who is not currently into K-pop be grooving to an Engrish SNSD song on his iPod anytime soon? Not a chance.

Personally, I don’t believe so, nor do I believe it will ever happen… unless it is promoted as American music and not as K-pop (but at that point I don’t think it counts as being part of the Hallyu wave). But the thing is – I don’t think Korean companies are necessarily targeting the true mainstream like they tried to in the past. What they are doing this time around is targeting an already existing non-mainstream niche market and trying to work from there. They don’t need to secure new fans when they’ve already got legions of non-mainstream consumers patiently waiting for them to come to their home countries. They can still make a ton of money off these devoted fans, who would probably be more than willing to help manipulate album or digital sales to get positions on music charts (a TERRIBLE and unethical practice, by the way) so that our favorite K-pop groups can march on home with their heads held high and brag about how they took over America. But in reality, will an American who is not currently into K-pop be grooving to an Engrish SNSD song on his iPod anytime soon? Not a chance.

America has always had diversity in entertainment preference, with a certain (minority) sector of the youth population leaning towards Asian sources of media distributed through the internet. This sector of the population (densely populated by Asian Americans, but containing people of non-Asian descent as well) has ridden several waves, starting with a generation obsessed with T-pop (bolstered by T-dramas such as Meteor Garden, the grandparent of Boys Before Flowers) in the 90’s, J-pop (bolstered by anime and video games) at the turn of the century, K-pop (currently at its height) in recent times, and even the potential rise of C-pop (or so it is rumored) in the future. Many of these consumers turn to the internet for distraction due to a sense of disconnect with mainstream American media, whether it be due to ethnic or social reasons, and form new communities based on interests and values they personally find more relatable than those of their home country.

The reason why K-pop has experienced such a rapid global rise within the last two years is that Korean entertainment companies have only just now realized the full potential of using these internet and social media resources to connect to Western audiences. It used to be that music videos and variety shows were leaked online and distributed by fans with access to the source material. Now, companies have their own Youtube and Facebook accounts and directly distribute high-quality material to the internet public. Idols have started using Twitter to communicate directly with their global fans. Fans no longer have to spend a ton of effort looking for content of their favorite artists – they’re now shoved in our faces (maybe a little too much in terms of selca-addicts). It’s no wonder that K-pop fans have pretty much taken over the portion of the population that equally fervent J-pop fans occupied just five years ago.

But were these companies aware of just HOW effective their new methods were? Not until recently.

But were these companies aware of just HOW effective their new methods were? Not until recently.

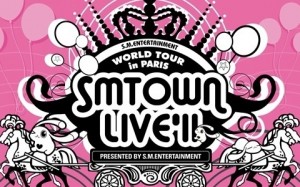

The resounding success of the sold-out concerts for SM Town Paris (and the flash mobs that started afterwards) was an unprecedented wake-up call to the industry.

In an interview, Kim Young-min, CEO of SM Entertainment stated:

“The response from European fans totally stunned us… now we feel more confident that we can take a plunge in the European market, albeit step by step.”

Entertainment companies were shocked to realize that they didn’t even have to produce (or recycle) new material catered to different cultures to secure these fans because the internet and voluntary fan translators had already done their work for them.

While in the past, it seemed that K-pop idols had to work very hard just to get the attention of foreign consumers (case example being the Wonder Girls’ attempts to secure the American tween market), lately the roles seem to have been reversed. It truly seems that with all the preexisting fans vying for attention from their favorite idol groups, right now there is a surplus of demand and not enough supply. This brings us to a very interesting question: While cult fan bases from countries all over the world are now there in place to accept K-pop, is K-pop ready to take on the demands of the world? Or have we caught them unprepared? Will they be able to produce and travel at a rate fast enough (without falling from exhaustion) to capitalize on our current needs?

This is actually something that worries me a lot about K-pop and its future. There is constantly such a high demand for immediate product that more often than not, quantity is prioritized over quality. In this globalizing age, K-pop acts are hastily trying to churn out new material and secure as much territory as possible in a short amount of time. I actually see this prioritization of quantity over quality translating over into the management of their overseas activities as well. Without establishing a very firm foundation in other countries, or a proper understanding of the culture of their new fanbase, they are already taking steps to export their product. And although many of their activities will be met with success (due to the devotion of fans), I can safely assume there are also going to be unprecedented setbacks based on hasty planning, miscommunication, and poor execution.

One case example would be the upcoming Free KBS Concert happening on October 9th at the Overpeck Park in New Jersey. From the start, the concert organizers showed a lack of foresight into understanding the needs of their new audience base. A few weeks after the highly publicized initial announcement of the concert, they were forced to relocate from the original venue in NYC to a suburb in New Jersey, due to issues with overcapacity. To make matters worse, the concert organizers put off announcing the details of ticketing information until a week prior the concert (and by this point THOUSANDS of fans across the country, including myself, had already planned out their trip in advance, and made non-refundable airplane and hotel reservations). Given that only a limited amount of tickets would be available for distribution at select locations in New Jersey/New York (on a first-come-first-serve basis), the majority of out-of-state fans were put in the bitter situation of having almost no chance of securing those tickets despite already individually having paid hundreds (collectively, that would make tens of thousands) of nonrefundable dollars on trip expenses.

One case example would be the upcoming Free KBS Concert happening on October 9th at the Overpeck Park in New Jersey. From the start, the concert organizers showed a lack of foresight into understanding the needs of their new audience base. A few weeks after the highly publicized initial announcement of the concert, they were forced to relocate from the original venue in NYC to a suburb in New Jersey, due to issues with overcapacity. To make matters worse, the concert organizers put off announcing the details of ticketing information until a week prior the concert (and by this point THOUSANDS of fans across the country, including myself, had already planned out their trip in advance, and made non-refundable airplane and hotel reservations). Given that only a limited amount of tickets would be available for distribution at select locations in New Jersey/New York (on a first-come-first-serve basis), the majority of out-of-state fans were put in the bitter situation of having almost no chance of securing those tickets despite already individually having paid hundreds (collectively, that would make tens of thousands) of nonrefundable dollars on trip expenses.

The result? Rather than gaining positive attention and press, KBS and the concert organizers managed to anger thousands of resentful (and now much poorer) American k-pop fans, all because of last-minute planning and poor communication. I am extremely bitter about this, if you can’t tell. Now I know exactly how those Japanese JYJ fans that flew to the Jeju Island 7 Wonders Concert felt back in July – except at least they still got to see a concert. Shame on you, KBS.

What happens when the quality of a product and basic understanding of consumer needs is not prioritized? A loss of respect. While we typically don’t place the blame on our beloved puppet idols, it does leave a bad taste in our mouths. Instead, we blame the managers, the corporations, even the culture. The outcome of the hasty and overeager nature of the Hallyu Wave movement is actually quite ironic. Korea wants to promote its public international image, by forcefully pushing its pop culture into different countries. On the surface, it has succeeded – legions of fans all over the globe have fallen in love with their favorite Korean idols. But through this same process, international fans also become intuitively aware of the darker aspects of Korean culture, which actually tarnishes its image.

The evidence is plastered all over this site. We blame the bad music, the gaudy concepts, and the overworking of artists on the corrupt and money-hungry companies. We blame the sexualization of underaged girls in the media on the deference to men in almost all aspects of Korean society. We blame the social receptiveness to plastic surgery for Korean women on an unfair system in which success for a woman (even when applying for a credentials-based job) is very much dependent on her looks.

The evidence is plastered all over this site. We blame the bad music, the gaudy concepts, and the overworking of artists on the corrupt and money-hungry companies. We blame the sexualization of underaged girls in the media on the deference to men in almost all aspects of Korean society. We blame the social receptiveness to plastic surgery for Korean women on an unfair system in which success for a woman (even when applying for a credentials-based job) is very much dependent on her looks.

The fact that K-pop seems to be running so fast across the globe at the moment makes me wonder when they are going to run out of steam. Running ahead without paving the road properly will inevitably cause unprecedented problems such as the recent KBS Free Concert ticket situation, which will ultimately result in an enforcement bad opinion about corporate Korea, even while strengthening our appreciation for our idols. Diving into the music market of other countries such as Japan with recycled songs without first having properly mastered the basics of its language will make the Korean music industry (and thus, Korea in general) come off as disrespectful and greedy, even as the idols gather the love and admiration of new fans.

Fans are often quite blind at first, but over time, as the glamour starts to fade, and we start becoming consumers that are much more aware of the actual system, even the dark aspects that these shiny images are supposed to disguise. And then we’ll start to talk.

If I were to asked to advise the K-pop industry on how to achieve true longevity and international respect, I would tell them to slow down a bit and be more concerned about the quality of its material, treatment of its artists, and respect for its fans. A bit of a more humble attitude wouldn’t hurt, either. But unfortunately I think they’re too focused on the short-term goals to care.

(Nate, BBC, The Jakarta Globe)