Fandom is a phenomenon that has grown to be a powerful movement in the world of celebrity culture. Most major celebrities in categories such as singer, gamer, or influencer have amassed fan bases that cover all different demographics yet are united by a “fandom name.”

The goal of fandom? To support their celebrity.

The combination of social media and globalization has made it much, much easier to show support for celebrities, regardless of physical location and cultural differences. As the world becomes more inclusive of other cultures, physical borders are no longer limits on influence. Globalization has become an everyday and vital factor that we use to find similarities between our shared human experiences while also judging and learning from our differences.

Fandom and globalization intersect most visibly in K-pop, and when the two are put together, the results are obvious. Trending hashtags, donation drives, awards show voting… These are all examples of K-pop fandom’s power. However, when this power is applied to social justice movements, things get complicated. Yes, fandom is capable of causing great good, but on the opposite side of the coin, it can become weaponized against the very people fans purport to support.

So what is a social movement, and how does fandom qualify as one?

Social movements are defined as a form of collective action that spans different networks and interactions between both groups and individuals, working towards a common goal that emerges out of the group’s collective identity. That may sound complicated until one realizes that… it simply describes fandom.

Think about it. K-pop fandoms span gender, race, age, sexuality, and they often take extremely effective action together in order to support their chosen artist/idol. There are weekly examples of this, from Twitter hashtag campaigns to organized birthday celebrations, mass voting and album purchasing, and more.

The idea of collectivism becomes even more important when viewed in the context of K-pop. Generally, collectivism focuses on the wellbeing of the overall community rather than individuals. This is especially evident in Asian countries where the family unit is emphasized more highly than the individual and can be seen in all different contexts, from company culture to an individual’s home life. Collectivism is crucial to understanding why K-pop fandom is so unified and efficient when attempting to reach a tangible goal.

Fandom takes up collectivism as a way of support and is thus able to synthesize millions of individual efforts into one result – all in the name of love for their celebrity.

Globalization has become a commonplace term to describe the exchange of ideas and cultural ideals to other countries in all facets of life. It is defined as, “… the relationship between the profound economic, social, political, and cultural changes going on in the modern world… collectively labeled ‘globalization’.” It is globalization that allows for different cultures to gain traction in countries other than their own.

In an American context, South Korea has had particular success in their efforts of globalization. For example, Korean films have recently left a huge impact. In March 2020, the Korean-language film Parasite won Best Picture at the Oscars following a sweep of other film awards throughout the year. In 2021, actress Youn Yuh-jung won Best Supporting Actress at the Oscars. Apart from the entertainment industry, Korean foods have also seen increased virality, such as the viral dalgona coffee trend.

Most noticeable, however, is K-pop. K-pop is a prime example of globalization, with groups such as BTS consistently selling out stadium tours. Other K-pop groups have also enjoyed increased media coverage in the West, with magazines such as Seventeen, Vogue, Refinery29 and more having features on K-pop artists.

Korean marketing companies also leverage globalization as much as possible. K-pop is shaped to have the most shareability. Consider reaction videos, a popular video format where someone reacts to a music video for the purpose of showcasing the reaction itself. With eye-catching visuals and sets, watching people watch K-pop videos is an experience in and of itself.

Reaction videos have become their own genre in the past years, with names such as ReacttotheK branding themselves by honing in on certain aspects of K-pop (in this example, the musicality). The fact that people can sustain entire channels off of K-pop specifically is a testimony to K-pop’s ability to garner interest and, on another level, interest in other people’s interest. This forms a sort of feedback loop that continually takes advantage of globalization and pushes K-pop into spheres that it may not have otherwise reached, such as students studying classical music.

Additionally, K-pop cannot be separated from Korean culture. The environment that created K-pop is highly collectivist and places high emphasis on the relationship between artist and fans, creating passionate and extreme fan cultures. The unique culture of K-pop showcases the efficiency of collective action. When used for good, K-pop fandoms are able to leverage their power to uplift groups and their good deeds, but when used for bad, it silences voices that go against the common goal of protecting and supporting their idol.

First, fandom is clearly an example of social movements. Fans from around the world organize informal networks of communication and act as a collective in order to urge individuals to take action in pursuit of a common goal. These goals can vary in scale and motivation, but all are in the name of a celebrity. Consider Twitter hashtag campaigns which K-pop fans are famous for trending on a worldwide scale. These can range from celebrating an idol’s birthday (“#BorntoVLoved,” “#HappyVDay” for BTS member V) to petitioning for members’ innocence over scandals, and even social justice.

For instance, STAY (Stray Kids’ fandom) constantly trends hashtags to show their love and support for member Hyunjin who was hit with a wave of bullying allegations in early spring. Regardless of right or wrong, the fandom has leveraged their power as a social movement to show their support and, in this case, give the company more reason to acquiesce to the fandom’s demands in order to keep their support.

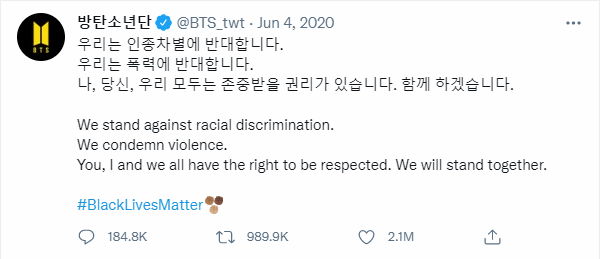

On the social justice end, the summer of 2020 saw BTS and Big Hit Entertainment donate $1 million to the Black Lives Matters movement. Within the day, #MatchaMillion began trending with the goal of ARMY matching BTS’ donation. In only twenty four hours, the organizers of the Twitter account managing donations announced that they had raised over $800,000.

BTS sent their initial tweet on Thursday, June 4.

By Sunday, June 7, ARMY had matched their donation.

This wasn’t the only time when K-pop made headlines in the political sphere. K-pop fans were lauded for other incidents such as flooding #WhiteLivesMatter hashtags with K-pop fandoms, thereby drowning out the racist rhetoric. Notably, K-pop fans also took credit for disrupting Donald Trump’s Tulsa rally by reserving tickets and not showing up, leading to Trump’s rally not even reaching 19,000 attendees. While the link was never directly proven, it certainly seems as though K-pop fans had once again used their platform to move as one unit, leading to tangible results.

However, fandom doesn’t always use its power responsibly.

On the negative side, there can also be organized campaigns to cover up wrongdoing. The goal of a social movement is always on behalf of a goal, and for K-pop fandoms, the goal is always to protect and uplift their idol.

No matter what.

Despite the outward appearance of social justice that K-pop fandoms had in summer of 2020, black K-pop fans have constantly spoken about their negative experiences in fandom. Over social media such as Twitter, fans who voice a different, more critical opinion over K-pop idols behavior (such as cultural appropriation, use of slurs, etc.) are often bombarded with hate and shut down. Often, it’s the very minorities that fandom is quick to proclaim they protect.

This sort of organized dogpiling isn’t just limited to legitimate scandals, but anything that could negatively affect the reputation of their idol. “Clearing the searches” is a popular practice where fans will flood search engines with positive terms in an attempt to drown out any slightly “bad” association that could gain traction. It’s a way to obscure information and, though seemingly childish, shows how fandom’s devotion to their idol often goes beyond any attempt to have a good faith discussion of right or wrong. Rather, it is preventative action to protect their idol.

From protesting against hate speech to lashing out at members in their community… What does it mean, then, that K-pop fans are so quick to swing from one extreme to another?

At the end of the day, social movements can be weaponized for good and bad. In their original intention, social movements are meant to cause positive change that impacts a larger group of people, and in this way, K-pop fandoms fail to match the definition. No matter how much good K-pop fandoms do, it’s important to remember that the goal of fandom based social movements always revolves around the celebrity. Fandom is certainly powerful, and harnessing its power can certainly help other goals, but K-pop fandoms doesn’t equal activism.

Remember: social movements have to have a goal, and in K-pop? That goal is a person—an idol.

Not justice.

(Variety [1], CNN [1], Medium [1], Refinery29 [1], Bloomberg Quicktake: Now [1], ReacttotheK [1], Lane Crofters, “Globalization and American Popular Culture,” Images via Medium)