Hwayugi (also known as A Korean Odyssey) has been exceedingly well-received beyond the borders of South Korea, broadcasted even on Netflix as a Netflix Original. Its success can be attributed to the very premise of the drama, adopting the familiar Chinese tale Journey to the West. Despite the numerous hiccups at the beginning — in which tvN has made their sincerest apologies — the drama is a thrilling fantasy romance story. However, to take it only at face value deprives it of the appreciation it deserves for delving into the depths of Korea’s socio-political situation.

Hwayugi (also known as A Korean Odyssey) has been exceedingly well-received beyond the borders of South Korea, broadcasted even on Netflix as a Netflix Original. Its success can be attributed to the very premise of the drama, adopting the familiar Chinese tale Journey to the West. Despite the numerous hiccups at the beginning — in which tvN has made their sincerest apologies — the drama is a thrilling fantasy romance story. However, to take it only at face value deprives it of the appreciation it deserves for delving into the depths of Korea’s socio-political situation.

The adaptation from Journey to the West, perhaps one of the most famous Chinese stories of all time, creates a frame that is already familiar for Chinese audiences globally. Such a tactic of narrative building draws in viewers who do not have to take the extra effort in understanding the references within the drama. Yet, as with every form of rewriting from cultural myths, there is an element of appropriation. For a Korean drama to borrow from a culture outside of their own adds an entirely different layer of complexity with regards to the question of cultural appropriation. How is Hwayugi then received as such an unproblematic construction? Kudos to the writers for creating a narrative that has successfully branched away from the original.

Journey to the West has been termed one of the four classic novels in Chinese literature (alongside Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Outlaws of the Marsh, and Dream of the Red Chamber). To map such a narrative onto Korean society is a bold move, especially when the original story depicts Tang Sanzang (Sam Jang) as a monk during the Tang Dynasty, tasked to retrieve Buddhist scriptures from India back to China. He is accompanied by the monkey god (Son Oh-gong), demon Sha Wujing (Sa Oh-jeong), a gluttonous and licentious man-pig demon Zhu Bajie (P.K./Jeo Pal-gye). These supernatural characters are given the opportunity to return to the celestial realm by assisting Tang Sanzang on his pilgrimage, with Tang Sanzang placing the headband on the monkey god’s head to keep him under control. In Hwayugi, the relationship between Tang Sanzang and the monkey god is transformed to a budding love story between Jin Seon-mi and Son Oh-gong.

This drama diverts attention from any potential criticisms of fouling a story focused on Buddhist values and the pilgrimage for enlightenment by situating itself in modern society, indicating outright that times have changed. The age-old story of Journey to the West can be reconceptualised from a fable of sorts into an epic tale of love (in its many forms of loyalty, friendship, family, even romance), and ultimately of self-sacrifice for love. To a certain extent, the cast itself plays an important role in deflecting away harsh criticisms.

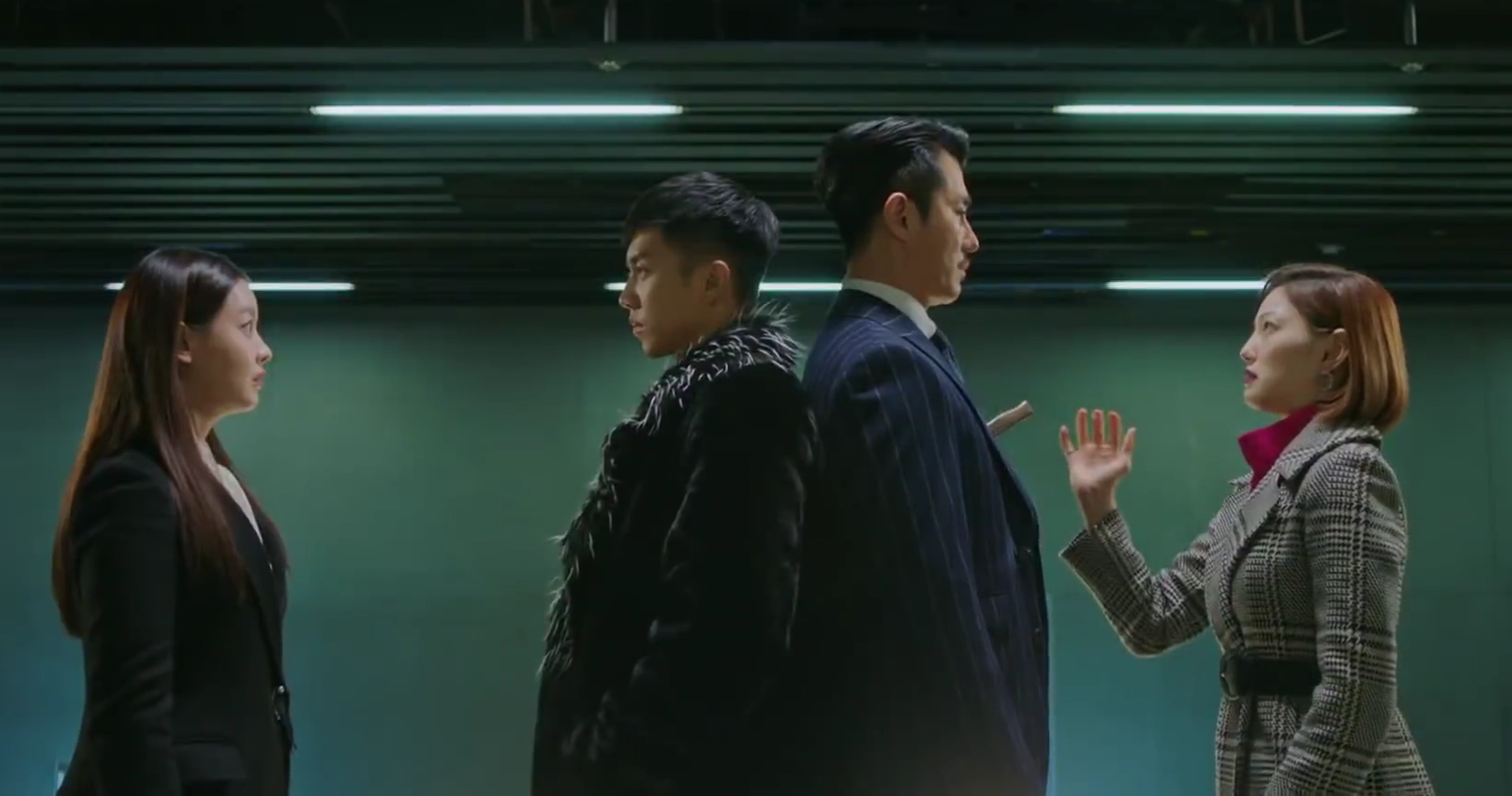

The drama has a pretty spectacular list of actors on board. Lee Seung-gi, affectionately referred to as the nation’s little brother, stars as Son Oh-gong; Cha Seung-won is Woo Ma-wang, a powerful bull demon and CEO of Lucifer Entertainment; and FT Island’s Lee Hong-ki takes on the role of PK/Jeo Pal-gye, a rock star under Lucifer Entertainment. Oh Yeon-seo plays the part of Jin Seon-mi/Sam Jang, while Lee Se-young brilliantly performs two different characters of Jung Se-ra/Jin Bu-ja, and Ah Sa-nyeo, a dead priestess that comes to possess the zombified body of the dead Jung Se-ra. The characters, all endearing and quirky in their own way, make it hard to shoot the drama down.

Even the antagonist, Kang Dae-sung (played by Song Jong-ho) channels such a strain of maliciousness balanced with charisma that immerses viewers completely in the fantastical dimension of the narrative — the good and absolute evil are split easily like in a children’s fairytale. Once the audience buys into a view of the drama as rooted in the supernatural, the filter of fantasy makes everything presented blindingly fascinating and easily acceptable as mere fiction.

The beauty of Hwayugi, however, is how it pulls away from the mythical back into the real as it approaches its conclusion. The fun and games of exorcising a handful of ordinary ghosts or evil spirits in the first half of the drama falls away as time goes by. The drama takes on a heavier tone by inserting Son Oh-gong into the political arena in competition with Kang Dae-sung. In doing so, they draw a solid line between the mythical and the real. Son Oh-gong, the embodiment of the supernatural, is given the important role of deterring an evil stemming from human greed for power in the political arena.

Furthermore, Sam Jang’s mission of saving the world is manifest in the images of nuclear destruction as Sam Jang gets prophetic visions of the future. Presenting the end of the world in such a manner is particularly poignant not only for South Korea, but also for an international audience. The increased concerns towards possession of nuclear power, especially with regards to North Korea, is unabashedly addressed in the drama.

With the thoughts of nuclear destruction in mind, the adaptation of Journey to the West then presents greater nuances to interpreting the drama. The drama offers a perspective of the large and ungraspable political situation in the present day, a situation that seems to be spiralling slowly out of control. In the face of such a world, this drama is a retreat from reality into the mythological to confront the problems of today. Even the reaching out into the narratives of another culture to communicate a Korean society is itself a turning away from the local and self. It is a grasping at something outside rather than looking within for solace, but it also reflects a desire to communicate a present situation to the world through the lens of the mystical.

Hwayugi brings to life characters that have had a long cultural record in Chinese literary history, yet it does not replicate the same pilgrimage to retrieve Buddhist scriptures. Within the drama, it is a different kind of journey in terms of learning to think beyond the self, and ultimately not only choosing self-sacrifice, but also understanding self-sacrifice from the perspective of others who have chosen to do so. It is a narrative that is not only entertaining in terms of the action-packed sequences it delivers or quaint characters. Embedded in its novelty is an attempt to ask viewers to be concerned about the plight of the world. In its own way, the drama uses apocalyptic images to scream its message to the audience: we need to talk about something more than entertainment; we need to pay attention to what is being said underneath the flourishes of magical powers and a fantastical world of demons.

(Dedalvs.com, MWave, SBS PopAsia, Shen Yun Performing Arts, The Straits Times, tvN, Vision Times. Images via tvN)