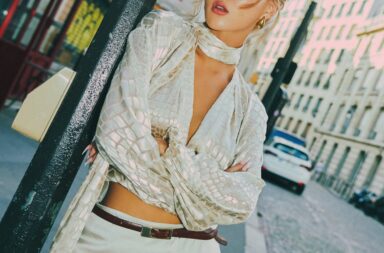

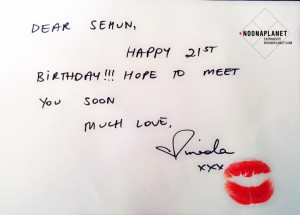

It wouldn’t be a surprise if Sehun oscillated between heavenly joy and earthly reality while chanting the lines “Hope to meet you soon” from Miranda Kerr’s recent birthday note to him. After all, going through an experience we can merely imagine about – our bias personally acknowledging our existence – is not written in everyone’s fate. Especially when none of us have a loyal fandom taking care of our most meager needs, working diligently at putting together gifts of epic proportions.

It wouldn’t be a surprise if Sehun oscillated between heavenly joy and earthly reality while chanting the lines “Hope to meet you soon” from Miranda Kerr’s recent birthday note to him. After all, going through an experience we can merely imagine about – our bias personally acknowledging our existence – is not written in everyone’s fate. Especially when none of us have a loyal fandom taking care of our most meager needs, working diligently at putting together gifts of epic proportions.

Jogong, or K-pop’s gift-giving subculture, is an intrinsic part of the idol industry. While on the surface, it appears as a mere gesture of expressing love and gratitude for an idol’s work, K-pop’s gift economy is actually a large and complicated system. It is not just a culture of giving material goods or making exorbitant charitable donations for the idols, it is an institution: a structure with its rules and laws governing the ebb and flow of tangible goods between fans and idols. Jogong may have shed its imperial past but its gift giving tradition aggressively endorses the existence of hierarchies between fans and idols, as well as between fans themselves.

Anthropologist and sociologist Marcel Mauss sums up the gift giving culture in three major points: the obligation to give, the obligation to receive, and the obligation to repay. Maintaining a balance between all these points prevents the gift economy from turning exploitative, except K-pop’s gift economy fails to fulfill the very first point and in a domino effect the whole institution crumbles down.

The act of gifting in K-pop is an extremely individual act. It is not an obligation; it is an indulgence, an extra something done for the idols. Ideally, there should be no coercion of any sort on the giver, and (s)he should gift only if (s)he wants to. However, it turns into an obligation when gift giving in K-pop takes on an organized identity with several fans collaborating with each other, when the gifts transcend from memorable trinkets to exorbitant displays of wealth and power, and especially, when they start to mark occasions like comebacks, birthdays, etc. With idols lapping up the gifts received, fans feel themselves bound in a tacit obligation to present their idols with gifts again, and again, and again. Entering once this obligatory territory of gift giving, fans get caught in its vicious cycle.

The act of gifting in K-pop is an extremely individual act. It is not an obligation; it is an indulgence, an extra something done for the idols. Ideally, there should be no coercion of any sort on the giver, and (s)he should gift only if (s)he wants to. However, it turns into an obligation when gift giving in K-pop takes on an organized identity with several fans collaborating with each other, when the gifts transcend from memorable trinkets to exorbitant displays of wealth and power, and especially, when they start to mark occasions like comebacks, birthdays, etc. With idols lapping up the gifts received, fans feel themselves bound in a tacit obligation to present their idols with gifts again, and again, and again. Entering once this obligatory territory of gift giving, fans get caught in its vicious cycle.

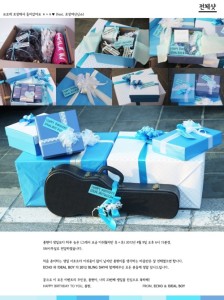

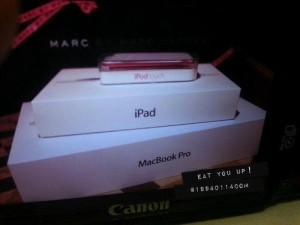

And it is not simply the repeated action of gift giving which becomes burdensome on young fans; it is the sheer excessiveness of the gifts. Fans –both individuals and groups – have taken it upon themselves to gift their idols the most expensive goods available in the market. From Playstations to Jaguars, there is a constant draining of finances with idols being gifted luxury goods. Fans have run into debts, taken loans, sold their valuables, collected money through unfair means for the sole purpose of buying immensely expensive gifts for their idols. The burdening aspect of this tradition goes unseen because fans are under the delusion that their self inflicted hardships are nothing compared to their idol’s happiness.

This blind idol worshipping reinstates the myth that gifting luxury products to idols brings fans closer to them and enriches the fan-idol relationship. With every increasing digit, givers assume an entitlement over the idols. “Since my gift was more expensive, I am a better fan” – Love is measured in crisp notes; loyalty comes with a Gucci tag. They are misled by the humble bows and beaming smiles of their idols that a ‘special’ relationship has been created between them, thanks to an imported perfume.

Wherever there is a gift giving culture, there will inevitably be a gift receiving culture, and unfortunately, the former thrives on the latter. The second part of the vicious cycle, the obligation to receive, dwindles between being a burden on and a privilege for the idol. On the one hand, the lure of luxury products is quite visceral. To reject a Jaguar hurts when one does not have the financial capability to afford one, and it hurts more when you are young and overwhelmed by material happiness. Regret over rejecting a rare gem of a gift is very natural, and idols might consider giving into their wishes, not fretting over morality. On the other hand, rejecting someone’s gift causes humiliation to the giver. It is imperative for the idols to receive the gifts because they are supposed to be tokens of love, and rejecting it would brandish them as obnoxious and pretentious. Idols are supposed to be the embodiment of good cultural values, the evaluation of “good” being contingent on the perceptions of fans, and offending their judges only sends their image to the gallows.

The problem doesn’t end with idols receiving gifts. In fact, it gets compounded. Receiving expensive gifts means an acknowledgement of the monetary value of the product and an assumption of a responsibility for the product. If the power dynamics were heavily biased towards idols in the obligation of giving, they get inverted here because the idols find themselves subservient to the ‘generosity’ of fans. The extravagance of the act may leave them shaken and also put an undue pressure on them to repay the gesture. Cube Entertainment‘s Ahn Hyo-jin asserts,

The problem doesn’t end with idols receiving gifts. In fact, it gets compounded. Receiving expensive gifts means an acknowledgement of the monetary value of the product and an assumption of a responsibility for the product. If the power dynamics were heavily biased towards idols in the obligation of giving, they get inverted here because the idols find themselves subservient to the ‘generosity’ of fans. The extravagance of the act may leave them shaken and also put an undue pressure on them to repay the gesture. Cube Entertainment‘s Ahn Hyo-jin asserts,

“It puts us in an uncomfortable situation when fans give excessive gifts. The company will return gifts that we feel are too much and try to lead them to giving to charities instead.”

This kind of intervention by the company is highly appreciated, especially in the case of baffled rookies who are not intensely familiar with the culture. When companies get into the picture, returning expensive gifts, the blame, hurt, and anger of the fans shift from idols to companies, and since fans are relatively disempowered, they usually slink away without causing much ruckus.

However, these are exceptional cases. With idols posting their birthday wishlists on social networking sites and eagerly receiving expensive gifts, simultaneously bragging about it online, fans even when given a way out, find themselves striding into the vicious cycle again. Encouragement of this sort turns the gift economy exploitative because the idols, ignorant of the means through which the gifts have been bought, egg the fans on to continue the tradition and end up endorsing their fans’ downward spiral. Their “Thank you” and “You guys are the best!” are meant to compensate for the money spent on the gifts and the effort put in by the fans and most of the times, fans are more than satisfied with it for it gives the repayment they yearn for the most – acknowledgement.

The obligation to repay balances the power disparities created by the first two features. It tries to take off the burden from the receiver by providing him a chance to give a gift of equal importance – financial and social – to the giver. It’s pretty obvious why this criterion is not met in K-pop’s gift economy.

The obligation to repay balances the power disparities created by the first two features. It tries to take off the burden from the receiver by providing him a chance to give a gift of equal importance – financial and social – to the giver. It’s pretty obvious why this criterion is not met in K-pop’s gift economy.

While an idol’s acknowledgement may seem of immense emotional importance, if one does the math, it amounts to nothing compared to the efforts put by fans. The idol’s albums don’t count as gifts because fans repay it by buying those albums – completing successfully one cycle of gift giving-receiving. There are rarely any gifts from idols. Even a glimpse of them in concerts is paid for.

Because of such a scarcity of gifts from idols, acknowledgement — being the only gift from their side — gains even more value than is healthy with fans competing with each other to get the best gifts across. It is a cutthroat competition out there with each fan trying to outdo the other on the basis of financial power, creating clear categories of the “haves” and the “have-nots.” Fandoms run into a frenzy trying to pool funds to get their idols the best of the best. And if anyone is unable to provide substantially for the cause, then not only does it lead to ostracism but also to abuse. For example, some Korean fans have felt compelled to work at extra part-time jobs to gather money for fansites.

Noble gifts like food support and charity donations – one of the most appreciable cultures of K-pop – get darker shades when fandoms turn them into a popularity contest. The one who gathers the more donations wins. The end result may seem favourable with a noble cause getting the required fund but it is at the cost of bullied and financially drained fans. Egos are hurt, spiteful conversations take place online and bitter rivalry runs amok – gift giving is no longer a sanctimonious act. Seoul University’s Psychology professor Kwak Geum-joo says,

“Fans feel a type of pleasure from giving gifts to celebrities. They turn their affections into a physical product, which promotes competition between each other. It’s not a healthy fandom culture at all.”

The acknowledgement issue gets more complicated with international fans. Finding themselves unable to actively support their idols by being physically present during concerts, fanmeets, etc., and constantly facing the jibes of native fans, being told they are not ‘loyal’ enough, international fans consider gifts as one of the most important means of expressing their loyalty and dedication. By presenting the most lavish arrangement of goods, international fans find the right to claim that they are as good as the Korean fans. Seemingly childish, recognition as a fan — not even that fan — just as a fan is important for people to feel themselves as part of the K-pop family, otherwise a casual viewer is too alienated from the K-pop essential of fan-idol relationship.

The acknowledgement issue gets more complicated with international fans. Finding themselves unable to actively support their idols by being physically present during concerts, fanmeets, etc., and constantly facing the jibes of native fans, being told they are not ‘loyal’ enough, international fans consider gifts as one of the most important means of expressing their loyalty and dedication. By presenting the most lavish arrangement of goods, international fans find the right to claim that they are as good as the Korean fans. Seemingly childish, recognition as a fan — not even that fan — just as a fan is important for people to feel themselves as part of the K-pop family, otherwise a casual viewer is too alienated from the K-pop essential of fan-idol relationship.

Coming full circle, gift giving is a generous act of love but it should remain an individual act, independent of other conditions such as popularity, loyalty, and dedication. Turning it into a harmful subculture really takes away a medium of appreciation. Gifts are great but there is a dire need to draw a line at the amount of and the amount spent on them. Capping the excess without tampering with individual agency is difficult, so where do you think should fans put a full stop? Considering VIXX’s negative stance on gifts, do you think idols should also learn to say no?

(Mwave, Daily Kpop, Soompi, Netizen Buzz, Kpopstarz, The Oneshots, Tumblr Images via Noona Planet, Eat You Up, Polar Light, shin soo hyun, SMTown)