Hear the rustle of a bespoke, Versace-esque, suit contorting with its gesticulating wearer, to dance beats thumping in the background? That’s the sound of someone striking a pose like there’s nothing to it, only this time it isn’t Madonna with her 1990 mega-hit, “Vogue.” Instead, it’s Shinhwa showing off the sophisticated sexiness that comes with maturity in the MV for their dance-pop hit, “This Love.” Shinhwa picks up where the ‘90s pop icon left off, borrowing their slick looks from the era and putting their vogue dancing skills on full display, by coupling balletic movements with angular postures, imitating models in fashion mags and figures in Egyptian hieroglyphs.

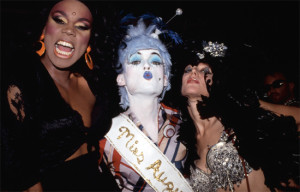

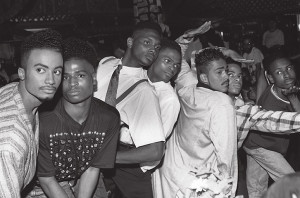

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=45wH_HHnJBg]While voguing seems like the Queen of Pop’s hand-me-downs, it originates from and remains a part of ball culture, a thriving underground scene in the black and Latino LGBTQ communities in New York and throughout the major cities of North America. Before Madonna gave voguing the pop treatment, legends like Willi and Benny Ninja were turning it out at balls: drag beauty pageants/dance battle competitions where contestants demonstrated artistry, glamor, and one-upmanship, expressed themselves freely, and celebrated their identities in the face of racism, homophobia, transphobia, sexism, and classism that were rife in society.

Once thrust into the mainstream spotlight, voguing shape-shifted into a short-lived pop culture phenomenon, tapping into the glam fashion world of the Supermodel Era. Now it finds itself in K-pop, helping acts like Shinhwa and 2PM cement their status as sexy, sophisticated, mature men. The journey of voguing from Harlem to Apgujong is one not only of geography and time, but of appropriation and repurposing, as well.

Once thrust into the mainstream spotlight, voguing shape-shifted into a short-lived pop culture phenomenon, tapping into the glam fashion world of the Supermodel Era. Now it finds itself in K-pop, helping acts like Shinhwa and 2PM cement their status as sexy, sophisticated, mature men. The journey of voguing from Harlem to Apgujong is one not only of geography and time, but of appropriation and repurposing, as well.

For those on the ball scene, voguing and “walking” (the dance and pageant ballroom competitions, respectively) are ways to embody the power, glamor, freedom of expression, and prosperity to which they, as gay, lesbian, and non-cis gendered people of color, often living in poverty, have little access. Channeling their inner Naomi Campbell, walkers stomp the runway, modeling designer looks and “serving” the audience with brash elegance and realness — the ability to convincingly take on another persona.

“Butch Queen Realness,” a walking category, is the ability to pass as a masculine, heterosexual male beyond the ballroom walls, while “European Runway” tests how credibly a competitor can imitate a female runway model in haute couture. Participants literally and figuratively walk in the shoes of the affluent, those with heterosexual male privilege, those with the advantage of cis-gendered beauty, and others who are not only accepted by society, but hold power in it.

“Butch Queen Realness,” a walking category, is the ability to pass as a masculine, heterosexual male beyond the ballroom walls, while “European Runway” tests how credibly a competitor can imitate a female runway model in haute couture. Participants literally and figuratively walk in the shoes of the affluent, those with heterosexual male privilege, those with the advantage of cis-gendered beauty, and others who are not only accepted by society, but hold power in it.

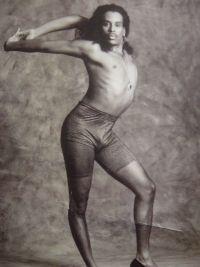

Vogue battles are fierce in many senses of the term. Merging the embodiment of high fashion glam with “reading,” the art of insult, competitors duke it out on the runway with poses, martial arts-inspired moves, ballet and modern dance stances, and fashion mag poses that display the voguer’s skill and, for the especially clever, mime or highlight the opponent’s flaws. Voguers aggressively command the floor, in stark contrast to their marginalized role in greater society. At the same time, they exhibit delicacy and grace, producing beautiful dancer’s lines, hitting those fashion mag poses, and displaying femininity–they dramatize aspirational glamor that, for most, is beyond their reach in the real world.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gtMtMy0ndo0]It was in the 1970s, about a decade after the scene developed in earnest, that ball culture as we know it started to take shape and voguing came to prominence. “Houses,” surrogate families often consisting of young people who’d faced ostracism from their own kin and communities, began organizing the balls and sending members to represent them in competition. By the late ’80s, sweeping change was coming to voguing. Stylistically, the “new” way — more athletic and with elements now common, like the duck walk and the shablam — was ushered in. The HIV/AIDS pandemic had begun to decimate the community. And the scene had caught the attention of many from the outside, including filmmaker Jenny Livingston, who made a documentary on the ball scene, Paris is Burning. It was around this time that voguing’s flashiness caught Madonna’s eye.

With its first major foray into pop culture by way of the Madge Express, voguing was taken out of its original context, becoming an emblem of ‘90s high fashion glamor and Euro-dance/house music of the era, as well as a short-lived dance craze. It’s now forever associated with Madonna in mainstream pop culture. While the poses, fantasy element, and fascination with style survived the transition from underground to mainstream, the association with people of color and the underlying motif of the struggle of the marginalized did not.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GuJQSAiODqI]After having been impressed by voguing in a New York club, becoming friends with people on the scene, learning from legends like Jose and Luis Xtravaganza, and working with producer Shep Pettibone to create the house music opus, Madonna released “Vogue” to global mega-success. Amidst a backdrop of smoky, Old Hollywood glamor, the Material Girl (how many monikers does one need, really) and her band of backing dancers introduced mainstream audiences to the dance in the MV.

The video, decidedly, took place far away from the ballrooms of Harlem. The song omits mention of ball culture or the context from which the dance came, too. In fact, the song somewhat explicitly decontextualizes voguing with the lyrics “it makes no difference if you’re black or white, if you’re a boy or a girl,” in referencing the ability or need to escape into the world of dance that Madonna sings about. Racial and gender disparities are part of the reason ball culture exists. It actually makes a huge difference.

The video, decidedly, took place far away from the ballrooms of Harlem. The song omits mention of ball culture or the context from which the dance came, too. In fact, the song somewhat explicitly decontextualizes voguing with the lyrics “it makes no difference if you’re black or white, if you’re a boy or a girl,” in referencing the ability or need to escape into the world of dance that Madonna sings about. Racial and gender disparities are part of the reason ball culture exists. It actually makes a huge difference.

“Vogue” became a worldwide phenomenon, topping charts on multiple continents and saturating the media with house music beats and images of men with high cheekbones and slicked back hair doing arm work. In the U.S., the dance became ubiquitous. People were doing it at sporting events, malls, parties, during recess in Mrs. Wright’s 2nd grade class (I remember), jokingly on late night talk shows, even on the runways of New York, Paris, and Milan. Fashion houses like Gianni Versace featured house music in their runway shows and referenced voguing, which cemented the dance’s link to high fashion. Voguing and its influence were everywhere… for a while. Then it faded back into obscurity.

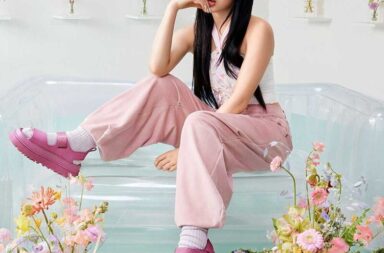

Fast forward two decades to the present, then head 8,000 miles west to South Korea — Shinhwa and 2PM are bringing voguing back, generally as part of this recent trend of ‘90’s revivalism, but specifically, to coopt the performance of glamor and sophistication in the dance to express their mature sensuality, giving voguing a different meaning in a new context. No long flower boys, Shinhwa and 2PM are flower men, now. Voguing seems like an appropriate medium through which K-pop idols can assert their maturity.

Fast forward two decades to the present, then head 8,000 miles west to South Korea — Shinhwa and 2PM are bringing voguing back, generally as part of this recent trend of ‘90’s revivalism, but specifically, to coopt the performance of glamor and sophistication in the dance to express their mature sensuality, giving voguing a different meaning in a new context. No long flower boys, Shinhwa and 2PM are flower men, now. Voguing seems like an appropriate medium through which K-pop idols can assert their maturity.

In many ways, voguing fits seamlessly into K-pop aesthetics. An emphasis on perfect execution of dance moves, a flair for the dramatic, an appreciation for soft, feminine male beauty and gender-bending, and often over-the-top fashions are just some similarities. But also, many times, both voguers and K-pop idols are wearing the figurative hats of others — those of fashion models and affluent voguers, and those of hip-hop heads and other members of music scenes with foreign origins in which authenticity holds a lot of currency, for K-pop idols. “Realness” is oftentimes an issue in K-pop, as it is in voguing: Wassup’s inability to serve twerking realness was both the coffin and the nail in it for that group’s chances at success, for example. Perhaps lessons in realness from voguing can be applied to K-pop.

“New York City is wrapped up in being LaBeija,” rasps Pepper, the matriarch of the House of LaBeija featured in Paris is Burning. At that moment in 1988, even with lofty aspirations for her sisters on the scene, she probably had no clue that within 25 years, it wouldn’t just be the Big Apple touched by the ladies who walk and serve, but that the world, at one point, would be transfixed by part of ball culture, if only for a brief moment in history. And that the reach of the artistry she was involved in would extend across continents and decades to 2013 K-pop. It will be interesting to see if the appearance of voguing in K-pop blossoms into a trend. One would hope that if voguing enjoys a day in the sun, that some of that light will shine on its past, too.

“New York City is wrapped up in being LaBeija,” rasps Pepper, the matriarch of the House of LaBeija featured in Paris is Burning. At that moment in 1988, even with lofty aspirations for her sisters on the scene, she probably had no clue that within 25 years, it wouldn’t just be the Big Apple touched by the ladies who walk and serve, but that the world, at one point, would be transfixed by part of ball culture, if only for a brief moment in history. And that the reach of the artistry she was involved in would extend across continents and decades to 2013 K-pop. It will be interesting to see if the appearance of voguing in K-pop blossoms into a trend. One would hope that if voguing enjoys a day in the sun, that some of that light will shine on its past, too.

(Boing Boing [1], Coffee Rhetoric [1], Huffington Post [1], Interrogating Dance Globalization [1], YouTube [1][2][3][4][5][6][7])