The term “slave contract” is not foreign to the K-pop industry, especially to the first and second generation of Korean idols. These contracts are notoriously known for their long contract terms, some even lasting 13 years, and their restrictive clauses that infringe on idols’ personal lives, such as a no-dating clause.

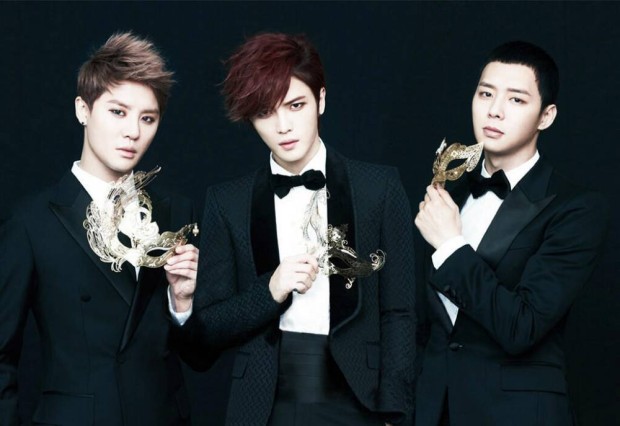

The first acknowledgement by authorities of this issue can be traced back to TVXQ’s court case in 2009. With TVXQ members Jaejoong, Yoochun, and Junsu filing a lawsuit and succeeding against SM Entertainment regarding the annulment of their contracts, the unfair contractual clauses and harsh working conditions that K-pop idols were subjected to were made known to the public. Following the lawsuit, the Fair Trade Commission set in place laws for agencies that dictated the need for fairer contracts, such as shortening the maximum number of years of a contractual term to seven years.

Since then, while much has changed in the K-pop industry, the slave contract still exists today, albeit taking on a more implicit form. Profit distribution is unfairly skewed to the company, with many entertainment companies operating by a “breakeven structure”, meaning that the money earned by the idol is used to pay off the costs of production and living expenses, placing most idols in a perpetual cycle of debt that can last for years before they even start to earn any money individually.

These oppressive conditions beg the question — why then do idols still sign these contracts?

Because this is the only way to compete in an overly saturated industry, apparently. According to Producer Ahn Joon Young, producer of MNET‘s Produce 101, “There are one to two new idol groups debuting every week, which amounts to more than 50 new groups coming out every year. Yet, at most only five teams are able to stay in the public’s mind.”

With this much competition, having an agency with connections and funding to secure a spot in mainstream media and other publicity avenues remain of utmost importance for idols wanting to be remembered by the public. Costs include paying an external public relations team just to ensure that the idol group has a chance to star on TV, which may not even be guaranteed due to the cut-throat demand. Idols also require a team of stylists, managers, promotional campaign organisers, choreographers, song producers, and more, just so that they can have regular comebacks and remain in the public eye, which would be an impossible feat for an independent idol. As such, idols who want to pursue their dreams have little choice but to sign slave contracts, placing them in a precarious position of financial debt and harsh working conditions. For example, Twice’s Momo revealed JYP Entertainment‘s harsh weight requirements for a photoshoot, which pushed her to eat only an ice cube for a week in order to lose weight.

However, in recent years, there has been a slow rise of trailblazers who possess both an agency to manage their promotions and having the freedom to manage their own working conditions. This alternative route is marked out by Idol-turned-CEOs; idols who left their agency and went on to establish their own, such as Jay Park, Zico, Kang Daniel, Hyorin, Highlight, and Shinhwa.

Jay Park‘s history is notable in this list, especially with his timely departure from 2PM after his old MySpace posts insulting Korea received heated attention. No one would expect that a year after becoming the nation’s enemy, he would make a successful comeback with his viral cover of “Nothin on You” on YouTube. With his successive album releases, exposure on SNL Korea as a cast member, and international concerts in the following years, he went on to co-found AOMG, a hip hop and R&B label, with Simon Dominic in 2013, and H1ghr Music, a Seattle and Korea-based hip-hop label with Cha Cha Malone in 2017.

Jay’s founding of his two hip hop labels cements his transition from an idol member to a leading figure of the Korean hip hop scene, and it showcases how inciting the public’s hatred does not necessarily mean an end to one’s stardom. The key benefit of owning an agency, namely, possessing artistic freedom, is one that Jay not only experiences as the CEO, but also extends to his artistes. In an interview with Forbes, Jay explained his philosophy behind managing artistes:

The thing with a lot of the bigger companies and labels is that they try to control what the artists do, in terms of everything. What they wear, what kind of music they put out, where the revenue is coming in, whatever it may be. They try to control everything. With us, there’s no set system.

Jay’s labels are proof that setting up your own label grants you both the financial freedom from slave contracts and the full support needed to survive in the entertainment industry. As a CEO, Jay has made it on Forbe’s list of 30 Under 30 – Asia – Entertainment & Sports 2017, and also has an estimated net worth of $10 million. Similarly, Jay himself stresses the importance of AOMG, and in extension agencies, for a celebrity’s branding:

We would take care of anything business related, and the fact that he [Korean Zombie, a celebrity signed under his label] was with us, kind of allowed him to partake in photoshoots, star in different variety shows, and increase his branding.”

Kang Daniel and Highlight are also notable examples of how being the CEO of an agency sustains and fuels one’s career as idols. As the nation’s number one pick on the second season of Produce 101, Kang rose to fame and popularity, only to be embroiled in a legal case with his company over their breach of his contract. Following his success in winning the case, Kang left his company and established Konnect Entertainment, an agency that currently only has him as its artiste, and that will fully support his career as an idol. The first MV that he released after establishing his agency, “What Are You Up To” gained a massive response with over 20 million views today.

Similarly, Highlight established its company, Around US Entertainment, to support their career as an idol group after leaving Cube Entertainment, with the exception of Jang Hyun Seung who did not terminate his contract with Cube. The transition was not without legal dispute as the group and company fought for the trademark of the group’s original name, Beast. When the group lost the case, it rebranded itself as Highlight under its new company, which marks a successful continuation of the career as a group and a close aversion of the infamous 7-year curse. Since the establishment of their own agency, the group has experimented with different forms of music and every member (with the exception of Yong Junhyung who has left the group after a scandal) has had the opportunity to release a solo mini-album of their own colour.

In contrast, while the members were under Cube Entertainment for seven years, only three of them — Jang Hyunseung, Yong Junhyung, and Yang Yoseob were able to release songs individually and promote as solo artistes. Hence, the establishment of Highlight’s company allowed the members a greater say in decisions and gave every member an increased amount of exposure.

The successful bounce-back recovery of these idols who have left their companies, often on a sour note, gives the future generation of idols another pathway to take after suffering from unfair slave contracts. Of course, with every successful Jay Park, Kang Daniel, and Highlight, there are hundreds of idols out there who are dismissed with a huge amount of debt to pay.

Yet, even if they are unable to set up their own company, we are seeing more idols successfully transferring to other companies. These idols and young bosses of K-pop create an optimistic narrative that Korean artistes have more freedom to choose, and are not bound to slave contracts or companies as tightly as in the past.

(The Korea Herald. Meaww. Variety. SBS Popasia. The Straits Times. Vlive. Forbes [1][2]. Celebrity Net Worth. Youtube. E! Online. Images via C-JeS Entertainment, MNET, AOMG, H1ghr Music, Konnect Entertainment, Around US Entertainment)