Medical dramas are inherently ugly yet exciting and uplifting at the same time. The grotesqueness of illness and injury puts viewers on edge. The uncertainty of whether or not the doctor can heal the patient keeps viewers on edge. The satisfaction when the doctor snatches a patient away from the clutches of death with minutes to spare ensures that viewers keep tuning in every week for more—just look at Grey’s Anatomy...

Medical dramas are inherently ugly yet exciting and uplifting at the same time. The grotesqueness of illness and injury puts viewers on edge. The uncertainty of whether or not the doctor can heal the patient keeps viewers on edge. The satisfaction when the doctor snatches a patient away from the clutches of death with minutes to spare ensures that viewers keep tuning in every week for more—just look at Grey’s Anatomy...

The same can be said for political and mystery dramas. The confusing yet captivating web of lies, accusations, collusions, confrontations, and red herrings keeps viewers glued to their seats and screens, rooting for the underdog to win and justice to be served.

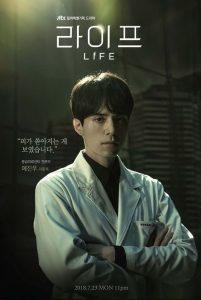

JTBC and Netflix join forces to give birth to Life. Life is a melodrama which combines medicine, mystery, and politics to address the moral implications of hospitals emphasizing profit over patients’ well-being. Cho Seung-woo, who previously starred in the tvN and Netflix drama Stranger, plays the suave and smirking antagonist, Goo Seung-hyo. Seung-hyo is the CEO of Sangkook University Hospital, which has recently been acquired by a corporation. Opposite Cho is Goblin‘s Lee Dong-wook, who plays the righteous Emergency Room doctor, Dr Ye Jin-woo.

Life begins with an alarm-blaring ambulance rushing through the Seoul traffic to Sangkook University Hospital. The hospital’s ER doctors, Jin-woo amongst them, rush to greet the ambulance. However, the ambulance’s sirens subside just before it reaches the hospital. A look inside the ambulance shows a man—later revealed to be the deputy director of the hospital, Dr Kim (Moon Sung-keun) slumped over, his clothes splattered with blood. He looks as if he has been murdered, presumably by the ambulance’s occupant. A second later, however, he asks Dr Ye the time in order to announce the patient’s time of death. The patient in question is revealed to be Dr Lee (Chun Ho-jin), current director of the hospital. This revelation causes the otherwise passive Jin-woo to tear up, hinting that he and the director were close.

Life begins with an alarm-blaring ambulance rushing through the Seoul traffic to Sangkook University Hospital. The hospital’s ER doctors, Jin-woo amongst them, rush to greet the ambulance. However, the ambulance’s sirens subside just before it reaches the hospital. A look inside the ambulance shows a man—later revealed to be the deputy director of the hospital, Dr Kim (Moon Sung-keun) slumped over, his clothes splattered with blood. He looks as if he has been murdered, presumably by the ambulance’s occupant. A second later, however, he asks Dr Ye the time in order to announce the patient’s time of death. The patient in question is revealed to be Dr Lee (Chun Ho-jin), current director of the hospital. This revelation causes the otherwise passive Jin-woo to tear up, hinting that he and the director were close.

The director’s death understandably causes shock, strife, and suspicious between the hospital staff. The hospital director and deputy director did not get along. Thus, Dr Kim’s claim that his senior came over already drunk to his house to share a drink with him and fell over the roof where he went up to smoke due to a heart attack, inspires skepticism given that he is the only primary witness.

This skepticism only worsens when Dr Kim announces at the staff meeting the morning after Dr Lee’s death that he agreed to a doctor-relocating program sponsored by the Ministry of Health. Under this program, the Emergency Room, Obstetrics and Gynecology, and Pediatric department would be relocated temporarily to a rural hospital to make up for the area’s lack of doctors.

This announcement forms the basis of conflict for the drama. It is no coincidence that the departments that amass the most losses in terms of revenue—Emergency Room, Obstetrics and Gynecology, and Pediatric—are the ones who have chosen to be relocated. The corporation who acquired the hospital only sees the bottom line, it seems, and not the long line of patients that need medical attention.

This announcement forms the basis of conflict for the drama. It is no coincidence that the departments that amass the most losses in terms of revenue—Emergency Room, Obstetrics and Gynecology, and Pediatric—are the ones who have chosen to be relocated. The corporation who acquired the hospital only sees the bottom line, it seems, and not the long line of patients that need medical attention.

Life revolves around money-driven hospital CEO, Seung-hyo, and empathy-driven doctor, Jin-woo, and his colleagues, dancing around each other. Seung-hyo is determined to restructure the hospital for increased productivity and increased profit, whereas Jin-woo and his fellow doctors are adamant to put patients first. While this premise is incredibly intriguing, given that it reflects the on-going debate about universal healthcare, Life promises too many genres but only delivers on one of them.

Doctors in life argue that the Emergency Room, Obstetrics and Gynecology, and Pediatric department are essential services. However, the drama doesn’t show me any heart-wrenching medical cases from each of those departments to convince me of this. Instead, doctors spend half their time in meeting rooms, arguing over the unfairness of being relocated. Thus, when Seung-hyo accuses the doctors of not following through on their promise of putting aside race, religion, and social status to help patients, I find myself agreeing with him.

Life also introduces me to a lot of characters in the first episode without giving me any of their names and expects me to remember their names and departments. The drama admittedly has a lot of strong female characters, but the lack of explanation of many of their names and roles makes it hard for me to root for them.

Lack of explanations is a recurring theme in Life. Jin-woo constantly to see apparitions of his brother, Seon-woo—who is very much alive—talking to him. Seung-hyo is also represented as a one-dimensional, greedy villain who gets rid of anything that doesn’t benefit him and sells his hospital’s patients’ data to insurance companies so they can use it to deny customer claims. Perhaps Jin-woo’s apparitions are a representation of guilt that Jin-woo feels because he is able-bodied and his brother isn’t? Perhaps Seung-hyo is greedy for money due to less than humble beginnings that Life only hints at? These questions simultaneously motivate me to keep watching the show yet also fast-forward through it because all that ever happens are meetings, discussions, and interrupted confrontations.

Lack of explanations is a recurring theme in Life. Jin-woo constantly to see apparitions of his brother, Seon-woo—who is very much alive—talking to him. Seung-hyo is also represented as a one-dimensional, greedy villain who gets rid of anything that doesn’t benefit him and sells his hospital’s patients’ data to insurance companies so they can use it to deny customer claims. Perhaps Jin-woo’s apparitions are a representation of guilt that Jin-woo feels because he is able-bodied and his brother isn’t? Perhaps Seung-hyo is greedy for money due to less than humble beginnings that Life only hints at? These questions simultaneously motivate me to keep watching the show yet also fast-forward through it because all that ever happens are meetings, discussions, and interrupted confrontations.

The cinematography of the show almost makes up for the lack of answers. Smooth camera pans, scenic shots of the Seoul skyline, and closeups of Seung-ho’s smug smirks shot in 2.35:1 aspect ratio make Life a pleasure to watch when I’m not struggling to fill in the gaps in the plotline. It seems that puzzling over Life will take years off my life.

(The Economist, Images via JTBC, Netflix)