This June opened with a US-North Korea summit in Singapore, with the fifty million-strong South Korean population anticipating what hopefully could lead to peace in the Korean peninsula in particular and some more chill time in East Asia in general. Also nine years ago this June, SNSD released what Billboard later crowned as the “definite SNSD sound”, a song that was “a little sweet and a whole lotta sexy,” the same song that would grow into becoming SNSD’s first non-Korean song: “Genie.”

This June opened with a US-North Korea summit in Singapore, with the fifty million-strong South Korean population anticipating what hopefully could lead to peace in the Korean peninsula in particular and some more chill time in East Asia in general. Also nine years ago this June, SNSD released what Billboard later crowned as the “definite SNSD sound”, a song that was “a little sweet and a whole lotta sexy,” the same song that would grow into becoming SNSD’s first non-Korean song: “Genie.”

These two events seem distinct, but hear me out: earlier this year, the two Koreas agreed to work towards repairing their relationship. The agreement accommodates the North’s demand that the South is to stop their megaspeaker campaign in the demilitarized zone (DMZ), meaning there’ll be no more regular broadcast of anti-Dear Leader messages and friendly capitalism PSA alongside IU’s “Heart,” Big Bang’s “Bang Bang Bang,” and… “Genie.” There you go: the song that is the first stepping stone for SNSD in its foreign venturing is also a weapon of propoganda in an on-going war.

The idea that music can and is used as a weapon of war is not novel: US operatives rickrollingly blasted Rick Astley’s “Never Gonna Give You Up” and ear-splitting hits from Guns ‘n Roses and KISS at Panama dictator Manuel Noriega as he was hiding at the Vatican Nunciature. Blur’s Damon Albarn refused to let American bombers use “Song 2” when launching in the Iraq War (woohoo!).

The idea that music can and is used as a weapon of war is not novel: US operatives rickrollingly blasted Rick Astley’s “Never Gonna Give You Up” and ear-splitting hits from Guns ‘n Roses and KISS at Panama dictator Manuel Noriega as he was hiding at the Vatican Nunciature. Blur’s Damon Albarn refused to let American bombers use “Song 2” when launching in the Iraq War (woohoo!).

The permanence of the cease of the synthesized loudness propaganda is also uncertain: in 2016 the South briefly reactivated the megaspeakers after a few previous years of a break following the North’s nuclear test. The inclusion of “Genie” in the megaspeaker campaign, officially called Operation Sound of Hope— a jab at the North’s Operation Sound of Freedom — was lampooned by The New York Times as the Hello Kitty Offensive, which, though condescending, makes sense. “Genie” is quite advanced in years compared to “Heart” or “Bang Bang Bang,” not is it as adrenaline-pumping as “Song 2.” Even within SNSD’s discography, it’s not as lyrically provocative as, say, “Run Devil Run,” or as teeth-grindingly, saccharinely sweet as “Gee.” So what is it about “Genie” that makes it a military-for-sale pop product par excellence?

Let’s take a look at the things “Genie” did right. It was SNSD’s first work with Western songwriters, namely the Norway-based Dsign Music. This collaboration would largely characterize SNSD’s music onward: part bubblegum pop, part Madonna-esque electropop (and, much later, some flirtations with R&B). Long story short, SM bought the song, called Dsign, and assigned SM’s regular Yoo Young-jin to co-write and produce it. This cemented the East-West mash-up philosophy of SM’s patriarch Lee Soo-man. What screams “Capitalism!” louder than this kind of mash-up for a Stalinist country as isolated as North Korea?

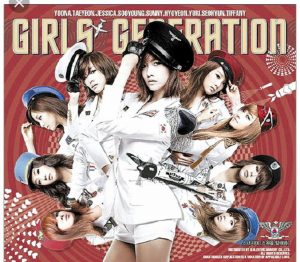

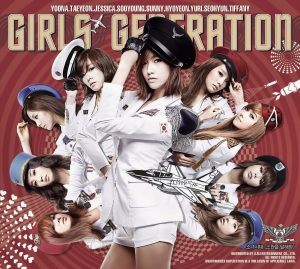

Visual-wise, SM never disclosed why they decided to go for a military theme for “Genie.” In 2012’s Complete MV Collection‘s commentary, the SNSD members said they found it “refreshing,” since they fittingly “got to wear shorts in summer.” Taeyeon had a fondness for its “cool charisma,” and Yuri was grateful for its giving fans a chance to see SNSD “in a different light.” That light meaning SNSD as grown women. The idea that military fashion is considered exemplary of maturity is neither new nor surprising. Teenagers can’t — and shouldn’t — fight a war. Adults in uniform do.

Controversy arose when SM’s creative team made the EP album cover whoozits and whatzits galore. From the figure of a Mitsubishi A6M Zero in the center to smaller-sized but equally disturbing Third Reich eagle pins on the girls’ hats, it’s war fetishization gone too far. Koreans never forgot how the Zeros, probably Japan’s most infamous war machine second only to the battleship Yamato, flew over the Korean peninsula in the 40’s. The furor forced a cover redo and a delay of the EP release. The girls’ stage costume, however, varied further to cover not only that of the navy but also the army and air force.

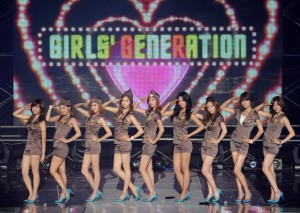

Furor forgiven, “Genie” owned the nation. Its July 2009 rooftop performance made record as MBC’s highest rating by K-pop stars in history. In August 2009, Psy joked on Kim Jung-eun’s Chocolate that servicemen swore allegiance to Country, Commander, and SNSD. And boy did they worship them, even sans uniform or formation that made this legendary mic-passing possible.

Through “Genie,” SNSD perfected juggling the military-civil dichotomy. On the one hand, the military poses an image of authority and audacity, orderliness and agitation. On the other hand, we know that the girls are not military. When SNSD’s 2011 Christmas Fairy Tale’s visit to a military base resulted in near hysteria, former The Atlantic editor Max Fisher wrote that as college-aged conscripts saw drafting as an inconvenient interruption of their lives, their SNSD experience was a return to normalcy. Everybody loved watching the girls in military uniform perform on stage, The Legs™ doing the jegichagi kick was recognizable from miles away. Later, it even made the list of State-sponsored (Nasty) Use of K-pop. Apparently, the South Korean audience could have their cake and eat it, too.

“Genie” Takes on Japan

Come fall 2010 in Tokyo, everyone and their grandmother knew the crab dance from “Gee.” SMAP’s Masahiro Nakai and the Oyaji Dancers put on colorful pants and lip-synced to “Gee” as Dad’s Generation. But I’m not going to lie here: SNSD came to me by way of Japanese. The Japanese version of “Genie” was my first SNSD/SJJD experience. As happy I was back then to see more of SJJD because of the success of “Gee,” I’d wished for more of their “Genie” personae for reasons — and not necessarily for their uniform.

Come fall 2010 in Tokyo, everyone and their grandmother knew the crab dance from “Gee.” SMAP’s Masahiro Nakai and the Oyaji Dancers put on colorful pants and lip-synced to “Gee” as Dad’s Generation. But I’m not going to lie here: SNSD came to me by way of Japanese. The Japanese version of “Genie” was my first SNSD/SJJD experience. As happy I was back then to see more of SJJD because of the success of “Gee,” I’d wished for more of their “Genie” personae for reasons — and not necessarily for their uniform.

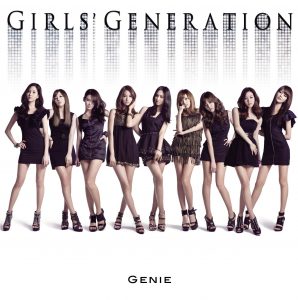

By the time “Genie” came to Japan — world’s second-largest music market after the US — it had become a K-pop staple. It was everywhere: in dramas, movies, and even in Big Bang’s Seungri’s “Let’s Talk About Love.” Yet, SM did not dress SJJD in military uniform for the single’s Japanese cover. Again, nobody could confirm whether this adjustment was done to avoid inciting a hawkish interpretation from the Japanese audience, especially considering the post-Occupation Japan-Korea dynamic.

What we can agree on is this: in the year span from the Korean debut to the Japanese release, “Genie” did its homework. 2010 marked the centennial of Japan’s annexation of Korea, and even though then-Prime Minister Naoto Kan had issued not one but two apologies that year alone, Japan still didn’t like to be reminded of its imperialist past.

SJJD’s small-stage outfits for “Genie” were policewoman-look-alike, camo jackets, and fuku-like onesies that only screamed “Military!” because of the insignias and epaulettes. Appearing less militaristic aside, at a time where top homegirls such as AKB48 were infantilized for marketing purpose, SJJD were promoted as grown-ups. You can’t enter the same market niche sporting the same weaponry as your competitors do, after all.

While the formula for the Korean version was sexy visual and sweet lyrics, Japanized “Genie” opted for sexy visuals and sexy lyrics, thanks to Kanata Nakamura’s rewriting of Yoo’s lyrics. In Nakamura’s version, the repetitive sowoneul malhaebwa was reborn as various lines, which, as the girls admitted in their Complete MV Collection commentary, were challenging to memorize. Gone was the “Material Girl” reference to Harleys and dreams cars. Also gone was the meek girl pleading in the lyrics. That girl was now a woman who declared that a relationship is a two-way work, that symbiosis needs communication, that wish-granting is conditional. She was an unapologetic J-popified Olivia Pope saying, “If you want me, earn me.”

While the formula for the Korean version was sexy visual and sweet lyrics, Japanized “Genie” opted for sexy visuals and sexy lyrics, thanks to Kanata Nakamura’s rewriting of Yoo’s lyrics. In Nakamura’s version, the repetitive sowoneul malhaebwa was reborn as various lines, which, as the girls admitted in their Complete MV Collection commentary, were challenging to memorize. Gone was the “Material Girl” reference to Harleys and dreams cars. Also gone was the meek girl pleading in the lyrics. That girl was now a woman who declared that a relationship is a two-way work, that symbiosis needs communication, that wish-granting is conditional. She was an unapologetic J-popified Olivia Pope saying, “If you want me, earn me.”

Did you call for me? That SOS?

Tell me now. Tell. Me.

Enough with your glossing over— say it selfishly.

Words have magic, surprisingly—your dream, that is.

If we’re together, we can do everything we wish.

If you go forward, give me a strong “go” sign.

If you start liking me, I’m “Genie” for your dream.

If you start liking me more, I’m “Genie” for your world.

Because even miracles have a process.

If only you come to me. If only you wish.

If only you want.

No war whatsoever there; just wants. Or, seen in a different light, borrowing Yuri’s words, it’s truly fighting a war to express wants in a society where your wants are often dismissed just because you’re a woman.

Accelerating the SJJD fever, “Genie” was the subject of a neurology study in Hokkaido that suggested it pumped excitement and helped brain development. SJJD’s eponymous debut album was the 2011 highest-selling album, even though its trailers looked like the makers were on an acid trip, and SJJD was the first non-Japanese girl group to have three number-one albums on the Oricon chart. In their first two years, SJJD had also held solo concerts, donated a partial revenue of “Mr. Taxi” and “Run Devil Run” sales to the Tohoku disaster relief, and gained an immense profit and popularity despite an anti-Hallyu sentiment in the latter half of 2011.

The Impact of “Genie”

Years after “Genie,” war remains in SNSD’s periphery. Psy’s joke aside, “Genie” remains a staple of the military in popular culture. North Korean serviceman Rhee Kang-seok in the drama King 2 Hearts (2012) was portrayed as harboring an appreciation of SNSD. Rhee almost caused an international conflict when he thought his South Korean counterparts made fun of his heart-eyeing the Genie MV.

Years after “Genie,” war remains in SNSD’s periphery. Psy’s joke aside, “Genie” remains a staple of the military in popular culture. North Korean serviceman Rhee Kang-seok in the drama King 2 Hearts (2012) was portrayed as harboring an appreciation of SNSD. Rhee almost caused an international conflict when he thought his South Korean counterparts made fun of his heart-eyeing the Genie MV.

I’ve heard of wars escalated by a football game or ridiculously waged against emus, but I’ve never seen anything more surreal than watching North and South Korean servicemen, fictional as they are, point guns at each other because of SNSD. That is; until Operation Sound of Hope happened. The North does not want its people to believe in hope, and god forbid one day its defector does confess of liking our wish-granting goddesses. “The best propaganda is not propaganda,” Harvard’s neoliberalism expert Joseph Nye states. A good weapon of war “Genie” is because it propagandizes not for hard power but for the human condition of wants — and propagandize to North Koreans “Genie” does sweetly.

On the other end of belligerence, though unrelated to “Genie,” the Japanese Occupation’s legacy reared its head again in 2016 through the whole Tiffany’s uninformed, ill-timed Imperial Rising Sun Flag fiasco. The fact that Tiffany came under heavier fire than The Walking Dead’s Steven Yeun, who more or less did the same just earlier in 2018, is for another discussion, probably one that will end up digging into misogyny — SNSD’s long-time frenemy — and bigotry as well. In all, the coda is the same: Tiffany was hostis publicus from then on.

“Genie” is not the first and won’t be the last piece of music used as a weapon of war. In South Korea, where the war sentiment is always strained in a tug of war between the Occupation era’s legacy and a future uncertainty regarding its unpredictable, and with a trigger-happy Northern sibling, what makes a better arsenal than the Nation’s Girl Group, as the drama A Gentleman’s Dignity (2012) proclaims?

“Genie” is not the first and won’t be the last piece of music used as a weapon of war. In South Korea, where the war sentiment is always strained in a tug of war between the Occupation era’s legacy and a future uncertainty regarding its unpredictable, and with a trigger-happy Northern sibling, what makes a better arsenal than the Nation’s Girl Group, as the drama A Gentleman’s Dignity (2012) proclaims?

In their tenth anniversary, the girls ranked “Genie” third for their Top 5 Songs. Fitting, I guess. This June is perhaps also a fitting time for me to bid a fond farewell to SJJD, whose last song was shadowed by Jessica’s exit and hasn’t released anything since. Perhaps it’s also an appropriate time — following the end of Operation Sound of Hope and the Singapore Summit — to admit that deep down I, too, have that war fetish. I love me some ladies who are dressed to kill, and I love me some ladies who are dressed to kill. While SJJD and I may come to a closure, the war fetish, and by association “Genie,” is here to last — today, tomorrow, and forever.

THERESIA PRATIWI has been trying to reconcile fangirling over Dvorak, Led Zeppelin, and SJJD all her life. She holds an MFA degree in Creative Writing from the University of Maryland and now works in southern Thailand.

(YouTube. Images via SM Entertainment, CBS News, SBS.)