As Sistar became the next successful girl group to disband, it’s been quite evident that there is no girl group that is immune to the Seven Year Curse. I wrote a post last October with several bold predictions on the fate of girl groups with expiring contracts and, as it turns out, many of them were wrong. Whether or not a girl group renews its initial contract has nothing to do with how well they’ve performed on the charts, how popular the individual members are, nor even how loved or respected they are by their fans. Sistar has proven that all of these factors are moot when it comes to the Seven Year Curse.

As Sistar became the next successful girl group to disband, it’s been quite evident that there is no girl group that is immune to the Seven Year Curse. I wrote a post last October with several bold predictions on the fate of girl groups with expiring contracts and, as it turns out, many of them were wrong. Whether or not a girl group renews its initial contract has nothing to do with how well they’ve performed on the charts, how popular the individual members are, nor even how loved or respected they are by their fans. Sistar has proven that all of these factors are moot when it comes to the Seven Year Curse.

In fact, there seems to be only one real factor in determining whether or not a girl group will renew their contract — the Rule of One. The Rule of One states that each entertainment company may only house one prevalent girl group at a time. This means that if a senior girl group is on an expiring contract and the company already has a junior girl group waiting in the wings, chances are that the senior girl group will disband to make way for their juniors. This was clearly the case with Sistar, 2NE1, 4Minute, Wonder Girls, and Rainbow. But before we start funneling hate towards these newer girl groups whose very existence caused the demise of some of our favorites, let’s dive into the economics behind why the Rule of One is such an effective indicator of whether or not a veteran girl group is likely to disband.

In order to understand the Rule of One, we must first comprehend the general business model behind girl groups. Girl groups rely on advertisement deals, also known as CFs, as their primary source of revenue. The highest earning female idols are popular girl group members who land the most CFs. The most sought-after idol spokesmodels are known as CF Queens — as their faces can be seen plastered on billboards everywhere. For entertainment companies, creating a CF Queen is the pot at the end of the girl group rainbow because that is where the real money is made.

In order to understand the Rule of One, we must first comprehend the general business model behind girl groups. Girl groups rely on advertisement deals, also known as CFs, as their primary source of revenue. The highest earning female idols are popular girl group members who land the most CFs. The most sought-after idol spokesmodels are known as CF Queens — as their faces can be seen plastered on billboards everywhere. For entertainment companies, creating a CF Queen is the pot at the end of the girl group rainbow because that is where the real money is made.

It’s no secret that youth is the greatest asset in this industry, especially when pertaining to girl groups. As CF Queens age out of their role, there are always newer and younger idols ready to take their place. In this sense, younger girl groups are inherently valuable because of their incredible upside. Whereas an established group like Sistar has already reached their peak in popularity, there’s no telling how much more popular their sister group, Cosmic Girls (WJSN), can get. In that sense, the aging group (Sistar) has a lower upside than the sister group (WJSN).

In terms of economics, a company will consider terms such as “earning potential” and “return on investment” when deciding who to spend their money on. Even though Sistar is more established than WJSN at the moment, and may be able to secure better advertising deals, their earning potential is limited due to their age. On the other hand, WJSN’s higher upside means that they have an earning potential that eclipses that of Sistar. In fact, some of WJSN’s more popular members are on the rise and may be in serious contention for CF Queen in the near future. In comparison, Sistar’s members have all hit their peaks and their days of competing for CF Queen are long gone.

Companies also lean heavily on return on investment in making financial decisions. For Sistar, their return on investment was very good up until June 4 when their rookie contract expired. The rookie contract which they were under since debut had terms which heavily favored the company. In order to regain the capital vested into training and debuting Sistar, the company likely forced the group to sign a highly unfavorable contract to ensure that the company would recoup their initial investment. Needless to say, Sistar had much more leverage at the bargaining table when it came time to renew their contract. However, Starship Entertainment, also had a huge bargaining chip which they brought to the table — Cosmic Girls.

Expectations are the crux of why it’s unlikely for girl groups to renew beyond their rookie contracts. From the perspective of the girl group members, some of whom may have become outright stars in the seven or so years since debut, they obviously want a contract that’s significantly better than the one they signed when they debuted. However, the company will likely lowball them with a contract that doesn’t nearly meet the terms they’re looking for and the two sides will walk away without ever making a sincere attempt to meet in the middle.

The reason this happens is because, most of the time, the company is not intent on re-signing the aging girl group to begin with, not when they have a younger girl group already established, one with an even higher earning potential. No matter what type of contract Sistar would have agreed to sign in order to continue as a group, it would in no way be as favorable to the company as the contract that WJSN are currently under. Therefore, Sistar’s return on investment would significantly dip under their new contract. Despite whatever official statements that the departing members or the company release, the cold hard truth is that the company would rather invest their future on a younger girl group with a higher earning potential and return on investment

Sometimes a company may gamble on renewing the contract of a veteran girl group in order to continue drawing revenue while they are in the process of establishing a newer girl group. This was likely the case with Kara who lasted two additional promotions after the contract expiration and departure of key members. Dal Shabet and T-ara are currently going through a similar phase as these groups continue promoting despite member departures. The remaining members of these groups likely settled for a decent short-term offer which allows them to continue promoting while their sister groups are trying to find their footing. In this sense, the Seven Year Curse is truly never broken, it is only delayed.

Sometimes a company may gamble on renewing the contract of a veteran girl group in order to continue drawing revenue while they are in the process of establishing a newer girl group. This was likely the case with Kara who lasted two additional promotions after the contract expiration and departure of key members. Dal Shabet and T-ara are currently going through a similar phase as these groups continue promoting despite member departures. The remaining members of these groups likely settled for a decent short-term offer which allows them to continue promoting while their sister groups are trying to find their footing. In this sense, the Seven Year Curse is truly never broken, it is only delayed.

The biggest shame is that the business model of girl groups does not allow for more than one thriving girl group to be under the same company (hence, the Rule of One) because the extra capital spent on promoting two girl groups does not justify the return on investment. I bet somewhere in the executive office of Starship Entertainment, there were people in suits looking at charts which compare the company’s projected revenues given two scenarios: with and without Sistar renewing. They likely found that the revenue stream for the Sistar renewing scenario is higher than the other. After all, Sistar’s popularity will likely land the company CFs that they otherwise wouldn’t get.

However, the executives also realized that a majority of CFs are likely obtainable even without Sistar being on board. In essence, if the cost of promoting two girl groups — at a significantly higher expense than of promoting just one girl group — does not lead to a large enough increase of revenue, then logic dictates that the company should spend more of their money on only one girl group, the one with a brighter future and a more favorable contract. In other words, it doesn’t make financial sense for Starship to house more than one girl group. Instead of splitting their investment on Sistar and WJSN, it’s a safer bet for Starship to invest their money solely on WJSN if they want a larger return on investment.

However, the executives also realized that a majority of CFs are likely obtainable even without Sistar being on board. In essence, if the cost of promoting two girl groups — at a significantly higher expense than of promoting just one girl group — does not lead to a large enough increase of revenue, then logic dictates that the company should spend more of their money on only one girl group, the one with a brighter future and a more favorable contract. In other words, it doesn’t make financial sense for Starship to house more than one girl group. Instead of splitting their investment on Sistar and WJSN, it’s a safer bet for Starship to invest their money solely on WJSN if they want a larger return on investment.

In order to further understand the business model behind girl groups, let’s compare the business model behind boy groups. Boy groups in general have greater longevity because their main source of revenue comes not from CFs, but from selling concerts and merchandise to their loyal fans. This business model allows a company to house multiple boy groups at once because these sources of revenue generally do not conflict. For example, iKon’s fandom does not greatly overlap with that of Winner’s fandom, and neither of these groups’ fandoms overlap too much with Big Bang’s fandom. Therefore, YG Entertainment can house three boy groups and still generate a high return on investment for each of them because each boy group generates its revenue stream independent of one another.

The same cannot be said for Black Pink and 2NE1, however, because their revenue streams overlap tremendously. For instance, if YG Entertainment enters into a contract with Samsung for the services of one idol spokesperson, then Black Pink and 2NE1 would be essentially in competition with one another for the same contract. That’s because the revenue pool for CFs is finite and it generates inter-company competition when there is more than one girl group under the same roof, which is not very conducive to return on investment.

The same cannot be said for Black Pink and 2NE1, however, because their revenue streams overlap tremendously. For instance, if YG Entertainment enters into a contract with Samsung for the services of one idol spokesperson, then Black Pink and 2NE1 would be essentially in competition with one another for the same contract. That’s because the revenue pool for CFs is finite and it generates inter-company competition when there is more than one girl group under the same roof, which is not very conducive to return on investment.

However, the revenue pool for boy groups can be much less limiting if they differentiate themselves enough to attract fandoms which do not overlap. As boy groups grow more experienced, and their fandom grows more mature (read: have more spending money as they age), boy groups can still generate a decent return on investment over time, making them less likely to disband and more likely to reunite after disbandment. The same, unfortunately, is not true of girl groups whose useful life expires when they reach a certain age and the CFs stop coming in.

With every rule, there’s always an exception. In this case, SM Entertainment seems to defy the fiscal logic set forth by the the Rule of One, currently housing three successful girl groups, and having renewed the contracts of senior girl groups in f(x) (allegedly) and SNSD despite already establishing Red Velvet. It’s safe to say that SM Entertainment, being the industry’s premier idol company, sets its own rules as all the big advertisers likely go to them before anyone else. In that sense, its hold on the industry is great enough that perhaps it justifies housing three girl groups at the same time. After all, f(x) and SNSD rarely get promotions anymore so it’s not like a ton of money is being spent in order to keep them under the same roof. As long as the return on investment is justified, then it’s possible to house multiple girl groups simultaneously. But how SM Entertainment manages this given the predicament set forth by the Rule of One is beyond my current comprehension.

With every rule, there’s always an exception. In this case, SM Entertainment seems to defy the fiscal logic set forth by the the Rule of One, currently housing three successful girl groups, and having renewed the contracts of senior girl groups in f(x) (allegedly) and SNSD despite already establishing Red Velvet. It’s safe to say that SM Entertainment, being the industry’s premier idol company, sets its own rules as all the big advertisers likely go to them before anyone else. In that sense, its hold on the industry is great enough that perhaps it justifies housing three girl groups at the same time. After all, f(x) and SNSD rarely get promotions anymore so it’s not like a ton of money is being spent in order to keep them under the same roof. As long as the return on investment is justified, then it’s possible to house multiple girl groups simultaneously. But how SM Entertainment manages this given the predicament set forth by the Rule of One is beyond my current comprehension.

Now that we understand why each company can only house one girl group at a time — barring some overlap in between the time it takes to establish a newer girl group and the older girl group’s contract to end, and with SM Entertainment being the sole exception — what does it mean for current girl groups who are coming up on expiring contracts? T-ara is likely to disband soon with the rise of DIA. Dal Shabet will have served their purpose once Dreamcatcher finds their footing. The remaining After School members are probably on the way out with Pristin having successfully debuted.

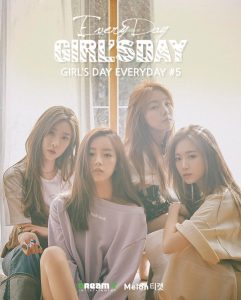

So, then who will remain to champion the old guard? Girl’s Day has renewed their contract, which doesn’t come as a surprise because their company has yet to debut a new girl group (though plans are supposedly in the works). A Pink will continue on as long as it takes their company to find a younger, more lucrative successor. Stellar may also renew given their company’s lack of a replacement plan for them. There are a couple of other veteran girl groups hanging around that I’m not going to get into but their time is numbered as long as their companies are planning to debut new girl groups.

I’ll conclude with an analogy that I hope will put the Rule of One into perspective — housing a girl group is a lot like owning a car. You may invest money into a car to ensure it runs smoothly over time. But as the car ages and breaks down more frequently, there comes a point where it would be a wiser investment to simply buy a new car as opposed to maintaining the old one. Once the new car is up and running, the old car is left with not much to do and it no longer makes sense to continue paying insurance on it so you end up getting rid of it. This isn’t a perfect analogy but it embodies the mentality behind making financial decisions that reinforce why sometimes it’s smarter to have only one of something.

In summary, the Rule of One states that a company can only maintain one girl group at a time. It’s not because they can’t afford to house multiple girl groups, it’s just that it makes more financial sense to invest more money on a younger girl group with a higher earning potential and return on investment than to allocate additional capital on an aging girl group with less upside.

Readers, what are your thoughts on the Rule of One? Are there girl groups I didn’t mention who support or diverge from this theory? Leave your thoughts below!

(Naver[1][2], Nate, Images via Starship Entertainment, YG Entertainment, SM Entertainment, Cosmopolitan, Dream Tea Entertainment, MBK Entertainment)