South Korea’s “obsession” with beauty is no secret. Of course, Hallyu culture promotes nearly unattainable — at least naturally — standards of beauty. Between the layers of BB Cream, small cosmetic touch ups, photo editing and styling, it’s almost impossible to know what is natural and what is manipulated.

South Korea’s “obsession” with beauty is no secret. Of course, Hallyu culture promotes nearly unattainable — at least naturally — standards of beauty. Between the layers of BB Cream, small cosmetic touch ups, photo editing and styling, it’s almost impossible to know what is natural and what is manipulated.

That being said, there are benefits to South Korea’s beauty and self care craze. Primarily, the healthy promotion of self care that is widely accessible and, most distinctively, gender neutral. In fact, Korea boasts the highest rate of male usage of cosmetic products — ranging from hair care and skin care to even make-up. Skin care in South Korea is understood as a matter of a healthy lifestyle, regardless of gender, and this sentiment is reflected in the widespread use of male idols as endorsers of popular skin care brands.

While it’s easy to get caught up in the habit of writing off South Korea’s beauty obsession as a plastic surgery craze and unhealthy promoter of unhealthy body image — or even plain consumerism — fans should also take a moment to acknowledge the positive aspects of a culture that unapologetically promotes self-care that doesn’t constrain itself to females. Self-care and beauty work can be, and should be, forms of positive self production. Not only does self-care come with the benefit of enhanced self esteem, but especially in the Korean context, it also brings positive social reward.

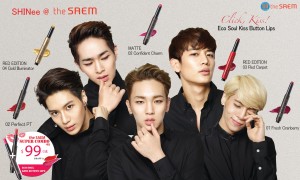

It’s common knowledge that idols rake in a majority of their income from endorsements, and skin care is just the tip of the idol-endorsement iceberg. The most popular of Korean skin care chains are endorsed by both male and female idol groups. Shinee currently endorses The Saem, which has also been endorsed by G-Dragon. Exo and Taeyeon (SNSD) are contracted with Nature Republic. F(x) represents Etude House, which up until 2014 was one of Shinee’s main endorsements. The boys of B1A4 lend their faces to Tony Moly alongside 4Minute‘s Hyuna. Actor Kim Woo-bin is the face of the more adult marketed chain Olive Young. Innisfree is sponsored by both Yoona and Lee Min-ho. The Face Shop is seemingly the only popular chain that limits their endorsements exclusively to a female model — but that’s probably because they make enough bank with Suzy as their spokes model that they needn’t bother with a male counterpart.

It’s common knowledge that idols rake in a majority of their income from endorsements, and skin care is just the tip of the idol-endorsement iceberg. The most popular of Korean skin care chains are endorsed by both male and female idol groups. Shinee currently endorses The Saem, which has also been endorsed by G-Dragon. Exo and Taeyeon (SNSD) are contracted with Nature Republic. F(x) represents Etude House, which up until 2014 was one of Shinee’s main endorsements. The boys of B1A4 lend their faces to Tony Moly alongside 4Minute‘s Hyuna. Actor Kim Woo-bin is the face of the more adult marketed chain Olive Young. Innisfree is sponsored by both Yoona and Lee Min-ho. The Face Shop is seemingly the only popular chain that limits their endorsements exclusively to a female model — but that’s probably because they make enough bank with Suzy as their spokes model that they needn’t bother with a male counterpart.

Why do these endorsements matter? The use of idol endorsements for popular skin care brands is an obviously smart marketing ploy. Fans — generally female — are sure to gravitate towards the brands their favorite idols endorse. Beyond the marketing, though, is the idea that males can benefit just as much from cosmetic products as females can if they so choose. Even if a majority of the products are purchased by females, they are by no means limited to only serving one gender, and it’s a mistake to say cosmetic companies only market towards females. Male idols’ casual use and documentation of skin care products outside of their endorsements makes this very clear.

Watching Shinee member Key demonstrate products on his Instagram doesn’t make me cringe at his perceived femininity — instead I am enthralled by exactly how healthy his skin looks. His gender should have nothing to do with the product he is selling me. Similar to their Etude days, with Shinee’s current Saem endorsements, the members not only promote skin care but even cosmetics. Cosmetics, just like skin care, are not inherently gender exclusive. There is no label that says “For Women Only” in bold letters on the packaging.

In fact, cosmetics and skin care products have seen a major raise in male consumption in the past few years in South Korea. There’s even a brand that makes special cosmetics and paints for military men that are gentler on the skin than traditional military paints. Cosmetics do not fully negate the hyper-masculine culture because many cosmetics are marketed and understood for their utilitarian value as opposed to their internationally gendered connotations.

In fact, cosmetics and skin care products have seen a major raise in male consumption in the past few years in South Korea. There’s even a brand that makes special cosmetics and paints for military men that are gentler on the skin than traditional military paints. Cosmetics do not fully negate the hyper-masculine culture because many cosmetics are marketed and understood for their utilitarian value as opposed to their internationally gendered connotations.

Furthermore, nothing about wearing make-up or using skin care products suggests that a South Korean male or idols desire to look more ‘feminine,’ and branding practices as ‘feminine’ with negative connotations only does a further disservice to femininity. In cases like male idols using cosmetics, ‘feminine’ is used to trivialize a set of practices and behaviors often associated with the female sex as a function of objectification. Practices like self-care, putting effort into appearance, ornamentation, etc, inherently have nothing to do with womanhood nor masculinity. Their female association is continually imposed through (misogynistic) social constructs that dictate that women have nothing more to offer than their appearance. Writing off male cosmetic use as a ‘feminine’ practice only continues the cycle of objectification.

Equally importantly, sets of gendered practices differ from culture to culture (though there are many overlaps). While international fans may have been socially conditioned to consider skin care, effort and make-up to be a production of the ‘feminine’ in our cultures, it doesn’t automatically mean the same for South Korea. There are still different expectations for male and female appearance, but for the most part neither of them have to do with the amount of effort put into looking good.

As earlier stated, skin in Korea is directly associated with perceptions of your health. Additionally, in a competitive job and social market like South Korea, appearance is a huge factor in the opportunities one is presented — how you present yourself matters and BB Cream does make skin appear clearer. Men use make-up and cosmetic products to have just as much of an edge up as their female counterparts — and it’s become a widely accepted practice. This hasn’t always been the case, but as the male market continues to expand, so do societal views on the matter.

This  becomes no more apparent than when one looks beyond the paid endorsements of male idols in K-pop. Male idols regularly boast about their skin care routines — Big Bang members engaged in a lengthy discussion of how to properly wash your face on Go Show; idols frequently post selcas of themselves in face masks; variety shows make a point of highlighting male skin care routines when they offer a glimpse inside an idol group’s dorm. There’s a matter of pride that is invested with knowing one looks good, and there is nothing wrong with flaunting the effort idols put in.

becomes no more apparent than when one looks beyond the paid endorsements of male idols in K-pop. Male idols regularly boast about their skin care routines — Big Bang members engaged in a lengthy discussion of how to properly wash your face on Go Show; idols frequently post selcas of themselves in face masks; variety shows make a point of highlighting male skin care routines when they offer a glimpse inside an idol group’s dorm. There’s a matter of pride that is invested with knowing one looks good, and there is nothing wrong with flaunting the effort idols put in.

Of course, these idols make money for upholding an image, so cosmetic routines are quite literally a way of saving face, but you rarely read or hear of an interviewer asking a Western male celebrity how he keeps his pores so small, though all celebrities undergo some sort of beauty work in their daily routine. One needs to look no further than Men’s Fitness’ ‘Grooming’ section to realize that male self-care is not unique to Korea, it’s just much less overt internationally. Western culture has an obsession with natural beauty, which means oftentimes we dismiss the work that goes into looking good — be it washing your face or moisturizing your skin — especially for male celebrities. South Korea doesn’t appear to hold the same obsession with natural — even idols with a “natural” face endorse skin products and cosmetics. Through overt showings of self-care, Idols help dispel the myth of “natural beauty” and instead acknowledge the ‘beauty work’ that is part of their every day routine.

There’s always the argument that male idol endorsements are nothing more than a trendy business strategy that plays into the unhealthy, beauty obsessed culture we so often critique. This may be true as customers are still chasing a relatively unattainable standard of beauty that they aren’t likely to achieve through snail emulsions or rice water cleanses — but there is a huge difference between dropping $30 on a skin product and surgically altering your entire face.

At the same time, marketing isn’t always a manipulative and evil force. Idol cosmetic endorsements are some of the more transparent forms of advertising. They serve as a constant and, for the most part, positive reminder that there is work behind that flawless complexion — be it male or female. On that note, gender inclusive idol marketing helps further advance progressive gender roles and counteract the prevalence of gendered advertising in South Korean media. Fans are going to envy Key’s flawless complexion just as much as Taeyeon’s, and nothing about it has to do with their respective genders.

At the same time, marketing isn’t always a manipulative and evil force. Idol cosmetic endorsements are some of the more transparent forms of advertising. They serve as a constant and, for the most part, positive reminder that there is work behind that flawless complexion — be it male or female. On that note, gender inclusive idol marketing helps further advance progressive gender roles and counteract the prevalence of gendered advertising in South Korean media. Fans are going to envy Key’s flawless complexion just as much as Taeyeon’s, and nothing about it has to do with their respective genders.

Even more interestingly, the use of male idol endorsers goes against the traditional principles of cosmetic marketing to males which generally include the product being as invisible, scentless and easy to use as possible. Instead, Korean idol marketing places value on not only the effects of the product but of the effort that one puts into maintaining their skin (look no further than Key’s Instagram). By marketing products as gender neutral, cosmetic companies not only work against the secretive nature of male self care, but more broadly help to shift away from the sexual objectification of beauty work – leveling self care as a more gender neutral method of maintaining one’s health.

At the end of the day, the initial confused reaction to the widespread use of make-up on male idols is understandable at first because it’s something many international fans aren’t as acquainted with. But, if watching male idols flaunt their flawless skin and complimentary lip balm gives you the heeby-jeebies, then I would argue that the fault lies not in the use of male idols but rather in your gender-biased thinking. Not only is gender a social construct, but we are also socially conditioned to associate certain products and practices with gender. There is nothing inherently feminine about make-up, skin care or cosmetics. Similarly, there is nothing wrong with taking care of your skin and wanting to look good — so long as the decision is being made for yourself and not as a response to societal pressures to look perfect.

(Korea Times, BBC, The New Yorker, Blisstree, New Republic, Wall Street Journal, Beyond Hallyu, The Grand Narrative, Images via The Saem, Nature Republic, Tony Moly, Olive Young, Twitter.)