What is the first Korean movie that would come to the mind of a K-pop fan? It might be something with their bias in the leading role, like one of T.O.P‘s movies, or a movie with one of the popular drama actors, e.g. A Werewolf Boy. If you are lucky, you could even get one with both.

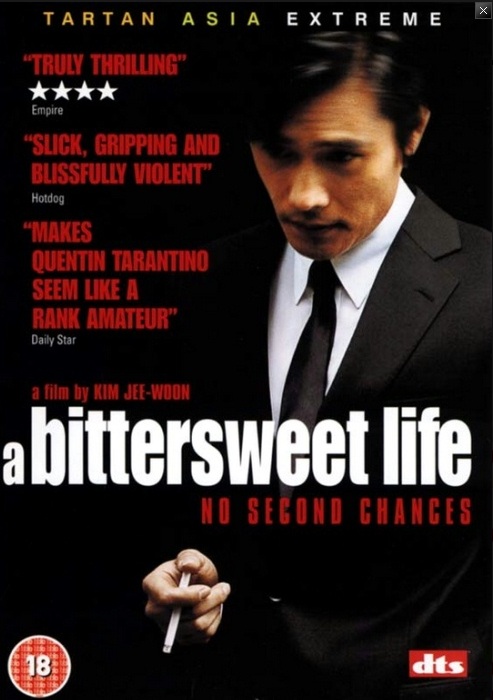

The answer would be a different one for people unaware of the pop and drama branches of Korean popular culture. With the rising popularity of South-Korean cinema over the last two decades, many would certainly refer to one of the violent and/or scary films which have been especially popular with foreign viewers. Among those, by now the revenge “genre” in particular is associated with South-Korean film-making. When searching for recommendations of Korean movies online, one can be sure to stumble across lists exclusively for Korean revenge movies sooner or later.

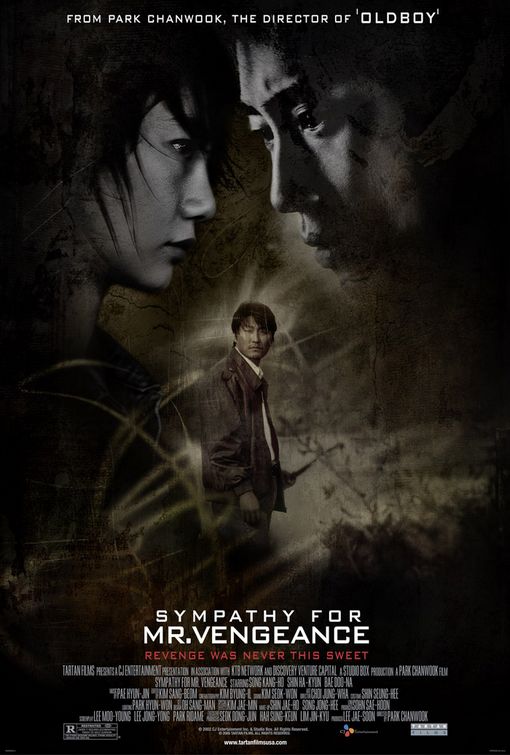

Ever since Park Chan-wook‘s Vengeance Trilogy (released between 2002 and 2005), the topic of revenge seems to have become especially prevalent, or at least more explicit than it was before. Among those who have noticed the trend, questions arise: Why is revenge such an important subject in South-Korean cinema? Where do the origins for this interest in the topic lie?

Scholars and knowledgeable laypeople seem to agree that South Korea’s past as a colony to its strong neighboring countries, a site of war in which families and friends were torn apart, and finally a country under dictatorship up until the late 1980s had a huge influence on this cinematic development. Film scholar Jinhee Choi therefore deems the description of the so-called Korean New Wave cinema (from the 1990s onwards) as “[a] cinema of post-trauma” as appropriate.

Throughout all of these years, the Korean citizens had been suppressed by their rulers. Due to this constant condition, the concept of “Han“, said to be an exclusively Korean state of being, evolved. This concept can have a variety of meanings, but in the context of this article the focus lies on the classical definition of the Chinese sign equivalent to the Korean word: “恨” can be translated as “unfulfilled vengeance”. Considering this translation, it stands to reason that the undercurrent of vengeful themes in many popular Korean movies might be a way of releasing this pent-up resentment and of fighting against one’s own perceived helplessness.

In this context, it is interesting to consider critic Jonathan McCalmont’s comment about how the drive of the lead characters in revenge movies (in this case Oldboy) reminds him of video game tactics:

“[A] fight scene is not about [how the] desire for vengeance necessarily leads to horrific violence, it is about how rewarding it can be to throw oneself into an activity and see tangible proof of one’s progress towards a particular goal.”

Apart from the reward, or by means of it, the gamer can also relieve stress. This is an important by-product of gaming. It also ties in well with the earlier theory of witnessing a man on a vengeful mission as being an opportunity to vicariously release one’s own frustrations.

Apart from the reward, or by means of it, the gamer can also relieve stress. This is an important by-product of gaming. It also ties in well with the earlier theory of witnessing a man on a vengeful mission as being an opportunity to vicariously release one’s own frustrations.

Which leads to the next point: Almost all the characters on a mission of revenge in Korean New Wave cinema are men. And noticeably often, the people they want to revenge are murdered women. Scholar Kim Kyung-hyun is of the opinion that the Korean cinema has been subjected to a remasculinization.

In his opinion, “one of the dominant tendencies of Korean cinema is to provide allegories of the nation through the figurations of tragic women.”

“Through the relegation of the political crisis onto the body of a woman, the male subjectivities in a modern environment are born. The disfiguration of the woman covers up their incompetence and instability.”

Meaning: Women embody the state, which is perceived as having failed the South-Korean citizens many times during the last few hundred years. By equaling women with the once easily dominated nation, men can shuffle off responsibility for everything that went wrong. And by revenging the woman/state, the “hero” can once again reclaim his masculinity which he considered to have lost due to the outside domination.

According to Kim, brutal killings (as they often happen at the end of revenge movies) “legitimize violence as the normative practice that disavows the fragile nature of masculine rationality.”

This could mean that after having lived in a state (=the “rationality”) which had been subjugated for so long, the revenge movie constitutes a chance for Korean men to renounce what they view as a weak collective and use the violence inherent in vengeance to reassert themselves.

This could mean that after having lived in a state (=the “rationality”) which had been subjugated for so long, the revenge movie constitutes a chance for Korean men to renounce what they view as a weak collective and use the violence inherent in vengeance to reassert themselves.

When considering this reassertion, it is worthwhile to note that many main characters of such movies, mostly average citizens, effectively have to become as brutal, almost inhuman as their enemy to be able to execute their revenge. And that the path of revenge frequently ends with death or suicide for the “hero”.

(“The South Korean Film Renaissance: Local Hitmakers, Global Provocateurs” by Jinhee Choi, “The Remasculinization of Korean Cinema” by Kyung Hyun Kim; asianwiki, MUBI, Modern Korean Cinema, Wikipedia, Ruthless Culture; images via Tartan Films, Showbox)