(Not apologising for the featured image, by the way.)

(Not apologising for the featured image, by the way.)

In light of the new JTBC Monday-Tuesday drama Secret Love Affair (starring Yoo Ah-in and Kim Hee-ae) adding on to the noona romance train starting the 17th of March, I decided that there’s no better time than now to discuss the use of this evergreen trope (it’s not just for the cute pictures, I swear it!).

For readers who recently descended down the dark, dark rabbit hole of K-dramas, it’s possible that you were only lately introduced to the dramaland trope of noona romance via dramas such as I Hear Your Voice (be still, beating heart!), The Woman Who Still Wants To Marry (starring Kim Bum and Park Jin-hee), or I Need Romance 3.

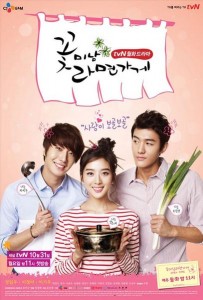

The trope itself, however, has been around for ages — older K-Drama fans may remember the 2005 trendy Biscuit Teacher Star Candy (featuring a much younger Gong Yoo — does the man even age? — and Gong Hyo-jin) and Jung Il-woo‘s teacher-adoring teenage rebel in 2007’s Unstoppable High Kick (Jung Il-woo, by the way, starred as yet another noona-loving high-schooler in tvN‘s 2011 release Flower Boy Ramyun Shop).

The trope itself, however, has been around for ages — older K-Drama fans may remember the 2005 trendy Biscuit Teacher Star Candy (featuring a much younger Gong Yoo — does the man even age? — and Gong Hyo-jin) and Jung Il-woo‘s teacher-adoring teenage rebel in 2007’s Unstoppable High Kick (Jung Il-woo, by the way, starred as yet another noona-loving high-schooler in tvN‘s 2011 release Flower Boy Ramyun Shop).

Noona romances are quite understandably an audience favourite owing to the character stereotypes involved; the male is typically an ambiguous shade of boy-man with the inherent flaws and attractions of both, while the noona is supposedly a (snerk) more rooted, mature working woman in an entirely different stage of life altogether. All of these come together in a potent confluence of Intense Appeal to woo audiences by the millions: an underdog romance that Shouldn’t Be But Must Be and a lot of cute (why else put Jung Il-woo in two of them?!). Who’s to say no?

Since we here at Seoulbeats are really into over-analysing everything (but it’s totally necessary!), I thought I’d break down the cultural appeal — and importance — of the noona romance in K-dramas. Social norms in South Korea, as most readers should be aware of by now, place heavy emphasis on patriarchal dominance (although, yes, they do have a female president), and this naturally extends to the personal and interpersonal spheres of life as well.

Noona romances thus challenge the conventional patriarchal power dynamics that typically play out in real life. It is this reversal of established gender roles that makes them even more satisfying than a drama with a Candy-type female lead who ends up having to be rescued from any and all situations of distress.

Noona romances thus challenge the conventional patriarchal power dynamics that typically play out in real life. It is this reversal of established gender roles that makes them even more satisfying than a drama with a Candy-type female lead who ends up having to be rescued from any and all situations of distress.

Being older and often in a position of authority, the female lead is empowered to override the whims and fancies of the male lead, especially given that he generally starts out dramas being entirely childish, full of himself, and generally in need of being taken down a peg (or a dozen pegs, actually). In Flower Boy Ramyun Shop, for instance, Lee Chung-ah‘s sassy former high school gangster owns the titular ramyun shop, and hence the rights to the employment of aforementioned flower boys as well, Jung Il-woo’s fantastically airheaded chaebol heir included.

The Korean viewership, therefore, is entitled via noona romances to a sort of vicarious enjoyment of a relationship likely to be quite different (in terms of who wears the pants, y’all) from the real-life norm — unless, of course, your wife is a gangster (just allow me this!). It also allows some breathing space for romantic attractions sometimes given the side-eye in everyday life — which older woman hasn’t ever encountered an intensely attractive younger man, but had to stop herself because of the difference in years? Age is, unfortunately, a very real obstacle to romances, and it can be hard to explain to your parents why you’re dating a pretty boy nine years younger and still in college.

Noona romances in dramaland thus allow us as viewers to live (or relive) these challenges and difficulties through the portrayal of the characters’ relationships. It offers a bittersweet dose of reality when the romance fails, and kudos to the dramas that handle this with a thoughtful sensitivity. The romance between the youngest son in family weekend drama, Ojakkyo Brothers, and his sister-in-law’s aunt (it’s complicated), for instance, is depicted as impossible, not for the impurity of affections, but because the boy-man himself simply has some growing up to do before he can romance anyone seriously. It isn’t all smiles and roses, but we as the audience feel the truth in the message the show sends.

Noona romances in dramaland thus allow us as viewers to live (or relive) these challenges and difficulties through the portrayal of the characters’ relationships. It offers a bittersweet dose of reality when the romance fails, and kudos to the dramas that handle this with a thoughtful sensitivity. The romance between the youngest son in family weekend drama, Ojakkyo Brothers, and his sister-in-law’s aunt (it’s complicated), for instance, is depicted as impossible, not for the impurity of affections, but because the boy-man himself simply has some growing up to do before he can romance anyone seriously. It isn’t all smiles and roses, but we as the audience feel the truth in the message the show sends.

Importantly, noona romances inevitably nudge viewers towards considering our own perceptions and assumptions of romance and relationships. What would make an older woman fall for a younger man? Can a younger man, buoyed by idealism and an often romanticised viewpoint of the lady in question, actually sustain a genuine, unwavering love for the older woman? Why shouldn’t two individuals who share a bond of love and understanding (pardon the cheese, but I mean this sincerely) be stopped from forming a romantic relationship like anyone else? And — perhaps more importantly — why should anyone feel more comfortable with a older man-younger woman pairing, or vice versa?

It’s important that the mainstream media does this button-pushing and keeps people asking those questions, because who else would? Television dramas have a wide reach, and have a staying power in the popular consciousness that is largely unmatched (people still make reference to 2006 “It” drama Princess Hours 8 years down the road!). To have such a powerful medium emphasise repeatedly the acceptability of unconventional romances and keep people thinking about why exactly they think things is, in my book, undeniably positive — it keeps society from stagnating in its value systems and holding on to any past oppressiveness.

It’s important that the mainstream media does this button-pushing and keeps people asking those questions, because who else would? Television dramas have a wide reach, and have a staying power in the popular consciousness that is largely unmatched (people still make reference to 2006 “It” drama Princess Hours 8 years down the road!). To have such a powerful medium emphasise repeatedly the acceptability of unconventional romances and keep people thinking about why exactly they think things is, in my book, undeniably positive — it keeps society from stagnating in its value systems and holding on to any past oppressiveness.

That being said, I do have my misgivings about the sheer saturation of noona romances on television, especially in recent years. Here’s a brief timeline for your reference, with the importance of the romance to the storyline indicated accordingly:

2005: Biscuit Teacher Star Candy (Main OTP)

2006: What’s Up Fox (Main OTP)

2006 – 2007: Unstoppable High Kick (Secondary/Supporting OTP)

2007: Bottom Of the 9th With 2 Outs (Secondary/Supporting OTP)

2008: My Sweet Seoul (Secondary/Supporting OTP)

2010: The Woman Who Still Wants To Marry (Main OTP)

2011: I Need Romance (Secondary/Supporting OTP), Flower Boy Ramyun Shop (Main OTP)

2011 – 2012: Ojakkyo Brothers (Secondary/Supporting OTP)

2012: I Do, I Do (Main OTP), Big (Main OTP — or maybe not, since the ending of the drama made no sense at all)

2013: I Hear Your Voice (Main OTP)

2014: I Need Romance 3 (Main OTP), Secret Love Affair (Main OTP)

Looking it over, we’ve been fairly swamped, haven’t we? Not all of these dramas handled the noona romance equally well (the mindfreak that was the finale of Big comes to mind); a niggling fear is that the treatment in the writing and directing of the noona romance will begin to play second fiddle to the unconventionality of the romance itself. Rather than offering thoughtful portrayals of a romance not yet fully acceptable by cultural norms, the focus could instead easily turn to making noona romances increasingly out of the ordinary, to play up the shock factor and lure audiences out of a burning curiosity.

Looking it over, we’ve been fairly swamped, haven’t we? Not all of these dramas handled the noona romance equally well (the mindfreak that was the finale of Big comes to mind); a niggling fear is that the treatment in the writing and directing of the noona romance will begin to play second fiddle to the unconventionality of the romance itself. Rather than offering thoughtful portrayals of a romance not yet fully acceptable by cultural norms, the focus could instead easily turn to making noona romances increasingly out of the ordinary, to play up the shock factor and lure audiences out of a burning curiosity.

It’s not that dramas can’t portray the relationships themselves carefully after first attracting attention via aggressive publicity of an unconventional romance, but I worry for the day when the hype becomes more important than the substance. Yoo Ah-in and Kim Hee-ae are absolutely riveting actors in their own right, both in terms of appearance and acting ability, but the registers of vocabulary employed by the Secret Love Affair publicity team sent warning bells going off in my head. The words “hot,” “passionate,” and “controversial” were tossed around a lot, and the media (and by extension the public) lapped it up accordingly.

The drama itself has a fairly scandalous premise — a young starving genius pianist in his twenties and the arts foundation president in her forties (who just so happens to be married to said pianist’s music teacher) become mired in an illicit relationship. Clearly, JTBC isn’t holding back with this one; fingers crossed that the content of the drama itself lives up to the publicity, and isn’t just relying on the shock factor to keep people watching.

The drama itself has a fairly scandalous premise — a young starving genius pianist in his twenties and the arts foundation president in her forties (who just so happens to be married to said pianist’s music teacher) become mired in an illicit relationship. Clearly, JTBC isn’t holding back with this one; fingers crossed that the content of the drama itself lives up to the publicity, and isn’t just relying on the shock factor to keep people watching.

I’m all for unconventional noona romances in dramas, but let’s keep them thoughtful enough to actually encourage progressive thinking in society, rather than leave viewers clutching their pearls and reeling from — well, everything. Sensitive, mature portrayals of romantic relationships that deviate from the norm shouldn’t be sacrificed at the altar of a shock fetish. It’s also been way, way too long since Yoo Ah-in has been a drama that didn’t have a lobotomy midway — four years since Sungkyunkwan Scandal?! Unacceptable. My moral compass will not allow for this. Secret Love Affair, you’d better be good. I’ve had a prayer circle going on for ages now.

(JTBC, KBS, MBC, Osen, SBS, tvN)