Let’s be clear. I don’t like aegyo. I don’t like the values it conveys. I don’t like its effects on a woman’s self esteem. I don’t like how it generates false perceptions. I don’t like its ability to swindle grown men’s pockets. And I most definitely don’t like how it makes the corporate fat cats rich.

Let’s be clear. I don’t like aegyo. I don’t like the values it conveys. I don’t like its effects on a woman’s self esteem. I don’t like how it generates false perceptions. I don’t like its ability to swindle grown men’s pockets. And I most definitely don’t like how it makes the corporate fat cats rich.

I also don’t like to talk badly about aegyo. In the current K-pop scene we have inherited, K-pop needs aegyo and aegyo needs K-pop. For better or for worse, aegyo has shouldered the way for K-pop’s success and K-pop has ridden the aegyo wave all the way to becoming the global industry it is today. Many of us would not know K-pop if not for aegyo. But let’s pause for a moment and understand why some may perceive aegyo as evil.

Aegyo is essentially a stereotype – a caricature of how a youthful female should look and behave. Stereotypes are harmful because they influence our perception of ourselves and others through externalities. They convey expectations on how one should dress, think, and act based upon one’s background. Stereotypes always accentuate the importance of certain traits at the complete expense of many others. Stereotypes are constantly being portrayed through mass media in the form of music and television. Here’s where aegyo needs K-pop. Aegyo relies on K-pop to broadcast its message. K-pop has definitely done its fair share in transmitting the aegyo image into the minds of millions of young girls. Gender socialization begins at an early age and has a massive effect on the mind upon the body reaching maturity.

Aegyo is indeed harmful because it tells grown women that they are valued higher in the eyes of men if they behave in a child-like manner. That’s because behaving like a child equals being submissive, which equals male approval, which equals good. All this plays into the concept of the male gaze which serves to objectify the female as a submissive sexual being whose sole purpose of existence is for the viewing pleasure of men. It is a form of disempowerment that is both harmful to women as well as to men. Women sacrifice their self-esteem learning to be overly submissive and dependent on men; meanwhile, men’s inflated expectations of the ideal (and unrealistic) aegyo woman are largely unmet by women in reality. Who actually benefits from this are the big businesses that market this image through mass media to encourage men and women to consume. Women spend money on products that make them more appealing to the male gaze and men spend money on women who most fit the male gaze.

Aegyo is indeed harmful because it tells grown women that they are valued higher in the eyes of men if they behave in a child-like manner. That’s because behaving like a child equals being submissive, which equals male approval, which equals good. All this plays into the concept of the male gaze which serves to objectify the female as a submissive sexual being whose sole purpose of existence is for the viewing pleasure of men. It is a form of disempowerment that is both harmful to women as well as to men. Women sacrifice their self-esteem learning to be overly submissive and dependent on men; meanwhile, men’s inflated expectations of the ideal (and unrealistic) aegyo woman are largely unmet by women in reality. Who actually benefits from this are the big businesses that market this image through mass media to encourage men and women to consume. Women spend money on products that make them more appealing to the male gaze and men spend money on women who most fit the male gaze.

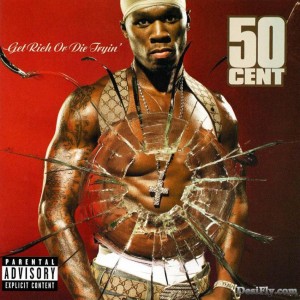

The perpetuation of harmful stereotypes for the sake of making a buck isn’t something that’s specific to K-pop. The US media sells many images of stereotypes largely based on race and gender. An example of such is the African-American male rapper. Here’s the story of a stylish, articulate, and swag-tastic minority figure who has made it big due to some luck but largely with hard work and determination – the classic American dream. But in order to get to where he is, chances are he had to drop out of school, join a gang, sell drugs, pop a few caps, and engage in all sorts of illegal activity to become the hardened thug that he is portrayed as being. This stereotypical image of the rapper tells the nation’s impoverished youth that it’s ok to drop out of school and commit felonies in order to be an aspiring rapper because that’s what 50 Cent had to do. The concept of the gangster rapper has been so fluidly submerged into the subculture of US ghettos that it results in an increased high school dropout, crime, and teen pregnancy rate – the allocators and self-regulators of poverty. And who wins? Nike, of course. Like the rapper, the aegyo stereotype is also highly problematic because of its tendency to reinforce particular cycles of oppression.

The perpetuation of harmful stereotypes for the sake of making a buck isn’t something that’s specific to K-pop. The US media sells many images of stereotypes largely based on race and gender. An example of such is the African-American male rapper. Here’s the story of a stylish, articulate, and swag-tastic minority figure who has made it big due to some luck but largely with hard work and determination – the classic American dream. But in order to get to where he is, chances are he had to drop out of school, join a gang, sell drugs, pop a few caps, and engage in all sorts of illegal activity to become the hardened thug that he is portrayed as being. This stereotypical image of the rapper tells the nation’s impoverished youth that it’s ok to drop out of school and commit felonies in order to be an aspiring rapper because that’s what 50 Cent had to do. The concept of the gangster rapper has been so fluidly submerged into the subculture of US ghettos that it results in an increased high school dropout, crime, and teen pregnancy rate – the allocators and self-regulators of poverty. And who wins? Nike, of course. Like the rapper, the aegyo stereotype is also highly problematic because of its tendency to reinforce particular cycles of oppression.

In case I haven’t made myself clear, I don’t condone aegyo. I am not trying to defend it or shed any positive light on a subject that is clearly detrimental to society. But it is a big part of K-pop and there are clearly reasons why it exists. So before we impose our own personal views upon the matter, it is important to understand the cultural context behind aegyo and why it has made K-pop so globally successful.

The global success of K-pop, what we call the Korean Wave (or Hallyu), has been largely credited to the proliferation of social media outlets such as YouTube, Twitter, Facebook, etc. However, what is neglected in this analysis is that K-pop is marketed more so to Asian countries than anything else. According to the Korean Wave Index of 2010, the main consumers of K-pop outside of Korea are Japan, Taiwan, China, Vietnam, and Thailand. One thing all these countries, including Korea, have in common is that they are countries which have historically been influenced by Confucian ideology. Without going into a detailed historical explanation on how Confucianism spread from its heartland of China into most of its surrounding regions, it’s important to note that out of the top five consumer nations of K-pop (Korea included), four of them are considered Confucian societies in which Confucian ideology is largely observed, practiced, and held in high regard. Thailand, being the only exception, considers Buddhism as its primary cultural and religious ideology; however, its population consists of a large minority (14%) of ethnic Chinese whose privileged social status plays an huge role in influencing Thailand’s economic and political spheres. Needless to say, Thailand is also highly influenced by Confucian ideology like other Asian countries that have succumbed to the Korean Wave.

The global success of K-pop, what we call the Korean Wave (or Hallyu), has been largely credited to the proliferation of social media outlets such as YouTube, Twitter, Facebook, etc. However, what is neglected in this analysis is that K-pop is marketed more so to Asian countries than anything else. According to the Korean Wave Index of 2010, the main consumers of K-pop outside of Korea are Japan, Taiwan, China, Vietnam, and Thailand. One thing all these countries, including Korea, have in common is that they are countries which have historically been influenced by Confucian ideology. Without going into a detailed historical explanation on how Confucianism spread from its heartland of China into most of its surrounding regions, it’s important to note that out of the top five consumer nations of K-pop (Korea included), four of them are considered Confucian societies in which Confucian ideology is largely observed, practiced, and held in high regard. Thailand, being the only exception, considers Buddhism as its primary cultural and religious ideology; however, its population consists of a large minority (14%) of ethnic Chinese whose privileged social status plays an huge role in influencing Thailand’s economic and political spheres. Needless to say, Thailand is also highly influenced by Confucian ideology like other Asian countries that have succumbed to the Korean Wave.

Since most consumers of K-pop are Asians who live in Confucian societies, it’s not surprising that the K-pop industry caters to the values and beliefs of Confucian ideology. One of the main tenants in Confucianism defines a woman’s proper role as being silent, hard-working, and compliant. While Confucian ideology is interpreted differently from country to country, most Confucian societies will agree that the traditional role of women includes something similar to the said definition. Korea’s interpretation takes this definition a step further in equating the woman’s role to that of a child. That is, women should be silent, hard-working, and compliant like a child; therefore, when a woman mimics a child it becomes a sign of her compliance to her expected role. Although aegyo is a definition that is specific to the cultural context of Korea, its cultural implications run deep into the moral and cultural backbone of Asia.

Here’s where K-pop needs aegyo. Let’s not forget that most of K-pop’s market remains predominantly in Asia and that its domestic and international fan base consists mostly of Asians. In the US, a region virtually free from the influence of Confucian ideology, the spread of K-pop lies primarily on its legion of “cult” fans who flock to K-pop events like KCON and SBS K-pop Super Concert. And who are the people one would most likely run into at one of these events? Asian-Americans! Whether they’re there to find a viable substitute for the lack of Asian-Americans in the mainstream media, or just there to get their aegyo fix, American K-pop fans represent a microcosm of K-pop’s worldwide fan base in that a majority of those with cultural roots reaching back to Confucianism, namely Asians, dictate the success of the industry. It’s not K-pop’s fault for meeting the demands of its majority fan base. The industry is simply responding to what its consumers want – female passivity with a healthy dose of aegyo.

Here’s where K-pop needs aegyo. Let’s not forget that most of K-pop’s market remains predominantly in Asia and that its domestic and international fan base consists mostly of Asians. In the US, a region virtually free from the influence of Confucian ideology, the spread of K-pop lies primarily on its legion of “cult” fans who flock to K-pop events like KCON and SBS K-pop Super Concert. And who are the people one would most likely run into at one of these events? Asian-Americans! Whether they’re there to find a viable substitute for the lack of Asian-Americans in the mainstream media, or just there to get their aegyo fix, American K-pop fans represent a microcosm of K-pop’s worldwide fan base in that a majority of those with cultural roots reaching back to Confucianism, namely Asians, dictate the success of the industry. It’s not K-pop’s fault for meeting the demands of its majority fan base. The industry is simply responding to what its consumers want – female passivity with a healthy dose of aegyo.

As for the aegyo bashing, I get it. Aegyo is offensive not just to me but to many Western consumers of K-pop, especially to female fans. We may have gotten into K-pop for reasons other than aegyo and feel the need to resent it for its distasteful presentation of women. I totally get it. But when I read comments like this,

“I detest aegyo but its tolerable on this group (for me) because they have this cute almost spunky way of doing it that makes it more funny then cringe-worthy,”

I can’t help but feel that the person making this comment is imparting her own ethnocentric views upon aegyo in justifying her reason for liking it. I also find it hypocritical that while there is so much “detest” for aegyo, there is still the inferred desire to consume it.

Although aegyo may be considered a detestable thing depending on one’s cultural background, so may cultural practices like the veil and arranged marriages. Just because we find something unsuitable to our cultural beliefs does NOT give us the right to insert our ethnocentric values into the context of another culture. Speaking negatively of a cultural practice or belief is highly offensive to those who abide by the victimized practice or belief. Similar to how one would not walk up to a Muslim woman on the street and question her values for wearing a veil, or publicly denounce a wedding ceremony because one disagrees with the arrangement of the bride and groom, we should not interject our own values and beliefs into questioning the use of aegyo in K-pop. As previously mentioned, aegyo is a defining characteristic of the genre and an intricate part of K-pop. There is no need to apologize for liking it. We are all here because we find it appealing or amusing in some shape or form. If aegyo is seriously so detestable and unbearable, then we wouldn’t be consuming it. But don’t feel the need to bash it and then provide hypocritical self-justification for liking it.

Although aegyo may be considered a detestable thing depending on one’s cultural background, so may cultural practices like the veil and arranged marriages. Just because we find something unsuitable to our cultural beliefs does NOT give us the right to insert our ethnocentric values into the context of another culture. Speaking negatively of a cultural practice or belief is highly offensive to those who abide by the victimized practice or belief. Similar to how one would not walk up to a Muslim woman on the street and question her values for wearing a veil, or publicly denounce a wedding ceremony because one disagrees with the arrangement of the bride and groom, we should not interject our own values and beliefs into questioning the use of aegyo in K-pop. As previously mentioned, aegyo is a defining characteristic of the genre and an intricate part of K-pop. There is no need to apologize for liking it. We are all here because we find it appealing or amusing in some shape or form. If aegyo is seriously so detestable and unbearable, then we wouldn’t be consuming it. But don’t feel the need to bash it and then provide hypocritical self-justification for liking it.

Lastly, if one were to bash aegyo, at least be mindful of others and qualify the comment by explaining why aegyo is so deplorable. If the cultural ramifications behind how aegyo promotes a stereotype that is harmful to society are clearly laid out, then that would open dialogue on the deeper matter of the issue and provide a cultural context that Western, non-Western, Asian, and non-Asian viewers may come to grips with. But simply leaving a short, unqualified remark imposing one’s own values and beliefs without taking into regard the cultural context of aegyo is just plain ignorance. It’s certainly positive to raise awareness on an issue that has a significant impact on the importing and exporting cultures, but it’s definitely wrong to condescend upon cultures not our own by imposing our ethnocentric values and beliefs upon them.

Lastly, if one were to bash aegyo, at least be mindful of others and qualify the comment by explaining why aegyo is so deplorable. If the cultural ramifications behind how aegyo promotes a stereotype that is harmful to society are clearly laid out, then that would open dialogue on the deeper matter of the issue and provide a cultural context that Western, non-Western, Asian, and non-Asian viewers may come to grips with. But simply leaving a short, unqualified remark imposing one’s own values and beliefs without taking into regard the cultural context of aegyo is just plain ignorance. It’s certainly positive to raise awareness on an issue that has a significant impact on the importing and exporting cultures, but it’s definitely wrong to condescend upon cultures not our own by imposing our ethnocentric values and beliefs upon them.

Just to be clear, I don’t like aegyo. In fact, I hate it just as much as (if not more than) any other Western fan of K-pop. For the record, I prefer strong women who own their sexuality (Miss A), but I also occasionally enjoy the teeth-rotting sweetness of Orange Caramel. That’s because I like K-pop for what it is. I will not apologize for it and I definitely will not bash it.

(The Grand Narrative 1, 2, CIA, Webzine, Kenyon College, KBS, SBS, Loen Entertainment, Aftermath Entertainment, Pledis Entertainment)