If you have read any of the more analytical pieces done by Western journalists on Psy‘s viral success “Gangnam Style,” you may have come across the term 된장녀 (dwenjang-nyeo), or “bean paste girl” — the likes of which, they say, “Gangnam Style” is mocking through its satirical lyrics about girls who have the leisure time and cash to enjoy a cup of coffee. Ubiquitous in Seoul and actually quite easy to spot in many a coffee shop (particularly in the wealthier and trendier regions of Gangnam), the bean paste girl has become something of a fixture in contemporary South Korea, the object of vehement criticism and feminist-lite speculation.

If you have read any of the more analytical pieces done by Western journalists on Psy‘s viral success “Gangnam Style,” you may have come across the term 된장녀 (dwenjang-nyeo), or “bean paste girl” — the likes of which, they say, “Gangnam Style” is mocking through its satirical lyrics about girls who have the leisure time and cash to enjoy a cup of coffee. Ubiquitous in Seoul and actually quite easy to spot in many a coffee shop (particularly in the wealthier and trendier regions of Gangnam), the bean paste girl has become something of a fixture in contemporary South Korea, the object of vehement criticism and feminist-lite speculation.

But what, exactly, does the term “bean paste girl” mean, and where does it come from?

The term “bean paste girl” draws its name from…well, bean paste. Specifically, it refers to fermented soybean paste (된장, dwenjang), which is most often used to make bean paste stew soup, or 된장 찌개 (dwenjang jjigae) a humble, hearty, and cheap soup that is often found in small, low-key Korean restaurants. Thanks to the simplicity of its preparation and the ease with which can be adapted to various ingredients and settings, it is also a staple in the home and is generally served alongside rice and various banchan (side dishes). Many Korean families still make their own dwenjang, though it is definitely easier (and quicker, and likely even cheaper in some cases) to simply buy pre-made dwenjang from the grocery store for all of your dwenjang needs. A thick spoonful of the stuff will offer some pretty powerful flavor for any soup base, and many would probably agree that dwenjang (like its closely-related Japanese cousins, natto and miso) is an acquired taste.

But what do women have in common with bean paste stew, or the dwenjang from which it is rendered? Here, the answer is less clear. “Bean paste girl” has come to be associated with a variety of definitions, none of which can likely be declared official; a casual asking of three Korean friends yielded three completely different responses. However, what all definitions have in common is an emphasis on a noted preference for luxury goods and the finer things in life. The essential gist of the bean paste girl is that she is consumed with the thought of consuming, and her consumption trends tend towards the pricey, the designer, the imported, and the Western. She drapes herself in brand-name finery — and no, imitations do not count (perish the thought!).

The point of divergence in defining the bean paste girl is the nature of her obsession with designer goods and where the money she uses to purchase them comes from.

The point of divergence in defining the bean paste girl is the nature of her obsession with designer goods and where the money she uses to purchase them comes from.

The most common and accepted definition puts forth that the bean paste girl is by no means a wealthy girl or from a wealthy family, but she chooses to horde her money by living at home with her parents and eating cheap meals (like a bowl of dwenjang jjigae, which usually costs between 3500 – 4000 KRW, or $3-$4, at restaurants) so that she can spend the rest of her money on an outrageously expensive handbag and a black sesame green tea soy milk Frappuccino (available at Starbucks in South Korea for the totally reasonable price of 6500 KRW — nearly twice the price of that bowl of soup). Hence the term “bean paste girl.”

Other definitions paint the girl as someone who blows her money on designer finery to the point that she resorts to mooching off of her family friends, totally reduced to consuming a cheap and decidedly non-luxurious meal like dwenjang jjigae because she can’t afford anything else.

Yet another characterization paints her as little more than a wannabe Westerner, a girl who is positively dripping with brand names and very well might have something like $1,500 worth of clothes and accessories on her person, but if you take them all away, she’s nothing more than a shallow and bucolic Korean.

Finally, some valiant defenders of the bean paste stew girl will offer that she is something of a feminist icon, a girl who makes wise fiscal decisions and doesn’t rely on the help of parents or boyfriends to purchase the fancy playthings she desires. In light of recent K-pop trends, this version of the bean paste girl might be a sort of miss A feminist — she might have dropped $1,200 on that Chloe handbag, but dammit, at least all of the money spent was earned with her sweat, blood, and tears! Take that, society!

Whatever definition of the bean paste girl one chooses to accept, the bottom line stresses an almost fanatical everence for luxury goods, particularly those that have been imported from the decadent West. This is certainly not unique to South Korea; the very same brands that attract the eye of Koreans have the same pull all over Asia (and indeed, all over the world). A designer handbag (or one for every day of the week, if you’re so inclined) is a powerful status symbol that bespeaks affluence, breeding, a preference for that which the West regards as “high fashion” over that which is non-Western (read: lowbrow and tacky). Though the individual carrying the handbag in question may, in fact, be neither affluent nor particularly well-bred, the handbag itself has become indexed with societal meaning to the point where it doesn’t much matter if the wearer is a rich socialite as long as she looks the part — and indeed, the vast majority of those characterized as bean paste girls are by no means well-off.

There must, however, be a reason for why this “phenomenon” (if you want to call it that) has been branded with a derogatory name and attracted such a degree of attention in South Korea — and the budding anthropologist in me wishes to point to South Korea’s incredibly rapid and compressed modernization as the culprit.

There must, however, be a reason for why this “phenomenon” (if you want to call it that) has been branded with a derogatory name and attracted such a degree of attention in South Korea — and the budding anthropologist in me wishes to point to South Korea’s incredibly rapid and compressed modernization as the culprit.

Though you wouldn’t guess by looking at it now, the Korean War destroyed and impoverished South Korea to the point that even Ethiopia (which has never been rich, hegemonic, or terribly powerful) offered aid and financial assistance. For the first few decades of its existence as an independent state, South Korea lagged pitifully beyond North Korea in terms of economic growth and quality of life — so much so that some began to wonder if North Korea was proof that Communism was a viable (and even preferable) alternative to free market capitalism. Authoritarian ruler Park Chung-hee, who took power through a military coup in 1961 (and whose daughter, Park Geun-hye, is the current presidential candidate of South Korea’s Saenuri party), made economic development his top priority and endorsed a number of hard-line policies to achieve extremely rapid and unprecedented growth. Throughout his rule, South Koreans were consistently exhorted to tighten their belts, to live frugally, and to work tirelessly to boost South Korea’s weak domestic economy; kwasobi (Korean for “excessive spending”) was more or less equivalent to a four-letter word, and national government campaigns were launched to teach its evils to the Korean people.

But of course, by the 1990s, South Korea was no longer poor — and no longer was there any concern that North Korea was the stronger and wealthier state of the two. After decades of being warned against the dangers of kwasobi, Koreans began to wonder what the fuss was really all about. Hadn’t they pinched their pennies for long enough? No longer in dire straits, Koreans began to consume more non-essentials — and what previously earned the contemptuous label of kwasobi gradually came to be regarded with envy. Faced with the prospect of dollars in their pockets and expensive finery in newly-opened department stores, Korean people did what pretty much anyone else would do and went to town.

The difference here may be that a certain segment of South Korea overcompensated, and in doing so, elevated ownership of brand name products to an unheard of level of sophistication and class. South Korea’s upper echelons came to be associated with items of Western luxury, from shoes to cars to fine dining to coffee — and around them sprang up a class of those who wished to emulate their glamorous lifestyles. A society-wide lust and admiration for designer items has likely laid the groundwork for the bean paste girl’s emergence — and though she is spoken of with disdain, it isn’t as though a grand majority of the Korean population (and really, any population in the OECD) isn’t striving to do much the same thing.

The difference here may be that a certain segment of South Korea overcompensated, and in doing so, elevated ownership of brand name products to an unheard of level of sophistication and class. South Korea’s upper echelons came to be associated with items of Western luxury, from shoes to cars to fine dining to coffee — and around them sprang up a class of those who wished to emulate their glamorous lifestyles. A society-wide lust and admiration for designer items has likely laid the groundwork for the bean paste girl’s emergence — and though she is spoken of with disdain, it isn’t as though a grand majority of the Korean population (and really, any population in the OECD) isn’t striving to do much the same thing.

Considering the historical and economic factors that may have played a hand in producing the bean paste girl, one might rightly ask why there is no such thing as the bean paste boy. Rest assured, readers — he exists. It’s just that no one has yet to call him out on it yet. Department stores teeming with brand name products cater just as much to men as they do to women, but perhaps the visibility of designer products that women wear (clothes and handbags emblazoned with logos, for example) have led to their increased vilification. Or perhaps it simply boils down to the fact that South Korea’s gender equality record is appalling and abysmal, and the lack of a bean paste boy reflects a general societal disdain for criticizing men in public. Whatever the reason, young women are currently the target of criticism regarding spending outrageous sums of money on fanciness, and the situation does not look poised to change anytime soon.

Whether or not the bean paste girl phenomenon (and Psy’s loud call of attention to it) will lend itself to serious societal change remains to be seen — but readers, I’d say you’re probably now in a good position to spot the so-called bean paste stew girl in a Korean drama near you! What’s your take on the matter?

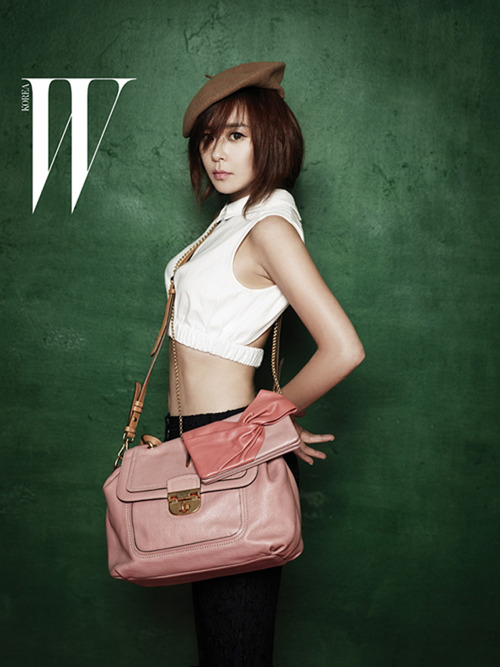

(Image Credits: [1], [2], The Atlantic, Laura C. Nelson, Measured Excess: Status, Gender, and Consumer Nationalism in South Korea (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000)