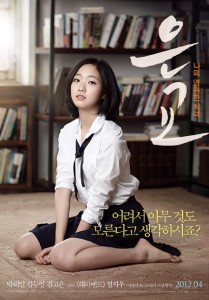

Earlier this year, a controversial movie heated up the world of Chungmuro: A Muse or Eun-gyo, a film whose main plot is the romance between a 70-year old man and a high school student. As it challenges many taboos, the story manages to raise a handful of valid questions, place some not-so-subtle social commentary and tackle uncomfortable universal truths. If you haven’t seen the movie, I strongly recommend it. It’s a great choice in terms of cinematography, acting and narrative. So let’s get to it, shall we?

Be aware, this review contains spoilers!

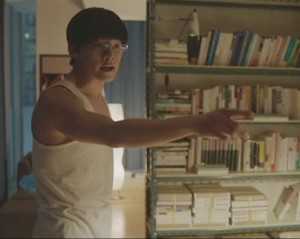

Before meeting the movie’s protagonist, the camera invites us to his home: an almost isolated house, beautiful, but simple and silent. Only after that, we catch a glimpse at Jeok-yo (Park Hae-il) as he undresses, looking at his reflection with an utter disgust. The routine takes over his day and he buries himself in books, while having a little fun with writing. He is after all the national poet. The link with the outside comes in the form of Ji-woo (Kim Mu-yeol), apparently his apprentice, companion and help. Their dull life changes when they find a stranger asleep on the porch: Eun-gyo (Kim Go-eun‘s first role). The girl is looking for a part-time job and predictably, she ends up doing chores around the house.

The contrast between Jeok-yo’s hateful look towards his body and his speechlessness as his sight wanders on Eun-gyo’s figure anticipates the conflict. The writer is fascinated by her youth, not only on the outside, but also by her versatility, will to live and kind, open heart. He’s meditative about his newly discovered feelings and adopts a passive, indulgent and secretive attitude towards his erotic desires and romantic attachment. He lets in our hands another confession: a 17-year old saved him from the communists. Besides linking Eun-gyo to that girl from his past, he associates her with freedom and a new beginning. By accepting her in his house, he claims his right to live as a human being and not as an afterthought to his life.

Just as your youth is not a prize for your efforts, my oldness is not a penalty for my faults.

To even fantasize about Eun-gyo, he needs to imagine himself younger, partially because he feels rejuvenated, partially because the image of an old man and a young woman is unacceptable even to him. The scene begs the watcher to ask himself: if a man in his thirties, such as the writer’s younger alter-ego, is granted the right to love Eun-gyo, why isn’t a man of a doubled age too? It challenges the perception of a normal young couple by placing this image into the mind of a senior citizen. The same critical eye directs two more scenes: Ji-woo reproaches him later in the movie that he’s a dirty old man for liking Eun-gyo because the girl is underage. However, he’s 30 and sleeps with a minor, but he never questions his actions, making viewers wonder how much the repugnance old people provoke counts in his moral judgment.

As Jeok-yo’s feelings for the girl evolve, he slowly detaches himself from Ji-woo. The latter stands for societal norms. He is rigid and prejudiced, without the capacity to understand differences. Everything and everybody is the result of a mass production, abiding the same rules. Often portrayed as a dense ex-engineering student, he is a sheep following Jeok-yo: he gets famous in his mentor’s area of expertise and even manifests an interest towards Eun-gyo because Jeok-yo’s judgment guides him. His lack of critical thinking or discriminatory ability reflects the absence of reasoning and thus true values in society.

What’s so special about that mirror? It’s just one of thousands from a factory.

We find out he doesn’t learn how to write from Jeok-yo, but he lets his superior to ghostwrite. Besides, he believes he actually gains value by doing so, as we can see in him celebrating supposedly his bestseller, The Heart. Ji-woo discovers Jeok-yo’s story about Eun-gyo and publishes it under his name. When confronted, he answers there’s no difference between The Heart and Eun-gyo, so why would the true author feel upset the second time and not the first? He claims Eun-gyo wouldn’t even be nominated at literary awards had it been written by an old man.

It’s not only Ji-woo’s audacity that startles the audience, but his sense of entitlement. After stealing Jeok-yo’s work and fancying Eun-gyo, he believes he’s more loyal than a son. In fact, the man doesn’t perceive Jeok-yo as a person at all. He doesn’t feel he took credit for another man’s writings or flirted with someone else’s love interest because he completely dehumanizes his alleged friend. It’s much like society puts Jeok-yo’s needs in some outskirts of life and completely devalues him just to turn around and regulate his existence if he dares to want one. An even sharper critique is addressed to a particular issue, prevalent in Korean society: the fight for social domination. Jeok-yo, as the national poet, is highly respected and considered noble. Ji-woo doesn’t understand it. He doesn’t even care if the award he had just received doesn’t belong to him. His social status is equal to his master’s or even better due, ironically, to Jeok-yo’s work or differently put, what other people see him worth of.

Completely the opposite, Eun-gyo is mostly instinctual and unaware of her beauty. She symbolizes impulsiveness and pleasure that doesn’t know a moral spectrum. Never censoring her employer, the girl doesn’t think twice about their relationship, she just lives according to her temporary state of mind. Her lack of knowledge about Jeok-yo or her oblivion concerning the effect she has on him present her as a deeply emotional, unthinking and free-spirited person. She lives, while Ji-woo judges. This is the main reason why the character needed to be this young: she hasn’t yet begun her life and she is allowed not to know.

Thank you for making me so pretty in your story. I never knew I was so pretty.

The two characters are different sides of the problem with their relationship. Always divergent, they don’t accept each other. However, they are only half-symbols and they’re humanized with their back-up stories. Ji-woo is unappreciated and never found his place. Eun-gyo lacks her parents’ love and has to figure out what she is to find her happiness. Both lack a fatherly figure that they encounter it in Jeok-yo. Their loneliness makes them compatible as much as youth does. It results though in a short and meaningless fling. Their night together points out the discrepancy with the pure nature of Jeok-yo and Eun-gyo’s relationship, even in its sexual aspect.

After the three characters tell their story, the movie takes a cheap twist. Jeok-yo sees the two of them together and tries to cause his rival a car accident. While Ji-woo enjoys the night with his partner, the old man tires himself arranging his car because of the overwhelming frustration. As his disciple falls for his trap, the writer is left with remorse. Eventually, the youngster is not injured and realizes his friend attempted murder. So he vengefully returns to the house, but his car is crushed on his way and dies. After this, I should at least stop spoiling the little rest of the movie and let you see the ending.

The fastening events towards the ending were really not necessary. There was a fine balance throughout the movie between the dreamy cinematography, the dialogue, the couple’s lighthearted moments and the overall progression in the narrative. The tragedy stroke unexpectedly, mostly as a question of whether Jeok-yo can live outside his social context to which we have a half-answer in the ending. We have the responsibility for the other half though.

As for the comparison to Lolita, there’s little and shallow. The age gap is hardly enough to compare them. Jeok-yo doesn’t force or trick Eun-gyo to stay with him. They both contribute to the relationship, which by definition goes against Nabokov‘s novel. While the writer likes Eun-gyo for the youth he no longer possesses and made him entitled, it’s not a form to deal with a repressed, altered and impossible to satisfy sex-drive. Also, Eun-gyo expresses a vivid interest in the old man’s wisdom. The movie attempts to deal with the psychology of the relationship by referring to its basic aspects: the old man’s pursuit for rejuvenation and Eun-gyo’s quest for a father figure. What could have made both the book and the movie better is a thorough explanation of her side.

The charm and the controversial stunt Jung Ji-woo (like the author of the novel, Park Bum-shin) is pulling consists in letting the two main characters develop their affection in a drama-like fashion while portraying the voice of the outside world in such a negative way through the cruelly written Ji-woo. He makes people empathize with an otherwise outrageous relationship. His arguments aren’t as rational as its counterarguments, but rather sentimental and dependent of the watcher’s. Regardless of your opinion on this subject, the movie humanizes the characters and offers you a unique perspective and food for thought, so why not?

If there are any readers who have watched it, what do you think? What’s your opinion on the topic?

(Lotte Entertainment)