Kara‘s Gyuri spoke up lately about an (un)usual contract policy, whereas the costs for her plastic surgery were being discussed with her parents. Snoop Dogg had a sudden epiphany and found out SNSD has no “biscuits,” but he confessed that he loves their legs and used a bucket of chicken thighs to show us just how much. Weekly, news sites, both Korean and international, feature polls about who has the most beautiful *insert body part here, eventually a food that describes it* for both female and male idols. AOA‘s members all play a certain role and one member’s talent is being beautiful. What these have in common is objectification, a common phenomenon in the K-popiverse and not only.

Now many rants and accusations have been made on the topic and I won’t beat the same dead horse again. Besides the usual explanations, there are some things though talks about objectification bring up. What got me here was an article about the way Korean women dress this summer, which included a feminist point of view:

Norms, mostly set by male-dominant societies, on appropriate outfits for women is a form of suppression. She also said female objectification underlies the issue concerning women’s body exposure in public. “This type of suppression is even more insidious than blatant sexism because of its subtlety and its pretense to support women while encouraging females to accept their own objectification”

So basically the women’s more provocative clothing, while it appears to be a sign of arrogating one’s self liberty, opens the way to women’s objectification, as those outfits present them as sexual commodities for men. While I can see where she is heading to, I have to disapprove (I’ll get back to this later). Shouting ‘objectification’ doesn’t settle an argument. The term itself refers to the reduction of a person to an object, process that meets different levels and stages. Furthermore, the definition hardly holds a rigid system of evaluation due to a vague, unclear line between subject and object. However, this is not the only issue and I would like to stress out some common misconceptions (in my opinion) about the term’s usage:

Sexuality: Emancipation or Objectification?

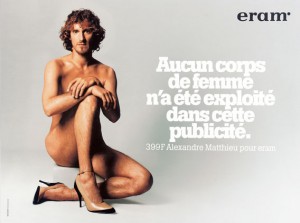

While it’s hard sometimes to identify the clues hidden underneath an allegedly inoffensive message, there is also a subtle line separating objectification from communicating through our body image. Conveying any kind of sexual behavior requires sending a message to someone — an abstract someone, representative for the target-group of the initiator. Sexual intercourse, as the name implies, involves more than one person: displaying the signs a community finds associated with sex, implicitly becoming sex objects, is our way of farther manifesting as sex subjects.

Nobody wears a banner saying ‘Screw me now,’ but a short skirt or a top that hints at a six-pack. Because of its plausible connection with bodies rather than personality, it is logical that our sexually-charged statements are both of the subject and the object —  they don’t exclude one another and on this realm, it’s impossible to do so. The ladies walking down the streets, dressed as they feel like dressing, have chosen their message; yes, it is a matter of emancipation and yes, it is a part of objectification, but they come together with adopting an attitude towards sex.

they don’t exclude one another and on this realm, it’s impossible to do so. The ladies walking down the streets, dressed as they feel like dressing, have chosen their message; yes, it is a matter of emancipation and yes, it is a part of objectification, but they come together with adopting an attitude towards sex.

The fuss around sexual objectification comes more from the taboo surrounding sex than the deep, humanitarian concern towards the people involved. Isn’t this attitude, after all, more objectifying than the objectification itself? Take Hyorin: the girl is flirtacious, funny, charismatic, energetic, talented and straightforward. But as soon as Sistar puts out another music video, there are two main topics: the sex-instrument talk and the whore-bashing. Both fail to acknowledge Hyorin’s personality. She displays a variety of traits on screen and yet, both fronts reduce her to a single part of her individuality: her sexuality. People need to face it: whenever a girl hints at sex, it’s not necessarily a declaration of independence or a sign of degradation, but one of her attributes.

The dichotomy body-personality imposes itself: you can have one or another. Sex is correlated to body, so a person who is sexually active can’t be smart or funny — these are aspects of the personality. The same way, women can be either promiscuous, dumb and shallow or intelligent, deeply moral virgins. In all the K-dramas, besides the main character, you can find the average bad girls. Not necessarily negative characters (in some cases sisters or friends), they are good-looking, a consistent trait in all dramas, have dated before and sometimes had sex. The tone when it comes to them is authoritarian and patronizing. The way they are depicted warns the viewer: a girl doesn’t want to become one of them and a boy shouldn’t be fooled into dating them. Why though the immediate association beauty/nice body – shallow/stupid/mean? Why can’t the body be in harmony with their personality?

Blame The Objectifier, Not the Objectified

I feel betrayed when regulating women’s behavior presents itself as a feminist direction because it goes completely against its initial purpose. Women should be able to act as they want to, as part of their freedom to choose. They shouldn’t be the ones on the receiving end of the critique, but the mentality and those who applaud it.

Especially the media, whose shady approach raises some serious questions. The image the TV and advertising industry offers for women is the source of prejudices and role models. Under 10% percent of the content we perceive goes to our conscious, the subconscious processes the rest, including the subtler implications. It is not to be said blatant messages never hit the screen: the image from your right is a collection of ads from your average newspaper site.

A history of treating women as commodities lies behind this burning issue, responsible for the objectifying gaze. The society lives in the aftermath of the gender roles’ assignment, which met its fluctuations in the past. The mass-media is both a reflection and a reflector of the standard mindset, which holds though the power to break the vicious circle. It is far more concerned though in using the female body to promote different products whilst criticizing the women for following a path it establishes: the unhealthy pursuit of physical perfection.

Objectification Is Not Just Sexual

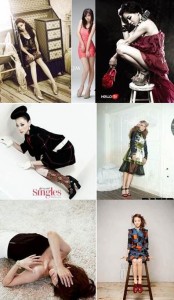

Different types of objectification allow a variety of means to disregard human beings. Haven’t you ever feel bothered by the way women appear in photoshoots? Inert or uncomfortable poses, their silhouette contorted, looking as if they were thrown on the floor, trying to fade in the background? That counts. Moreover, if you want to talk about the real problem with the idol industry, objectification affects the quality of para-social relationships. Even in our everyday lives, we meet plenty of individuals whom we don’t judge for their persons, but for their connection to us (waiters, pharmacists, mechanics). Objectification meets a scale of different levels and various outcomes.

Different types of objectification allow a variety of means to disregard human beings. Haven’t you ever feel bothered by the way women appear in photoshoots? Inert or uncomfortable poses, their silhouette contorted, looking as if they were thrown on the floor, trying to fade in the background? That counts. Moreover, if you want to talk about the real problem with the idol industry, objectification affects the quality of para-social relationships. Even in our everyday lives, we meet plenty of individuals whom we don’t judge for their persons, but for their connection to us (waiters, pharmacists, mechanics). Objectification meets a scale of different levels and various outcomes.

I’m not trying to minimize the issue. Objectification is a problem of high-importance on the feminist agenda not because it is the lowest morally-acceptable thing that ever happened (though arguably it is), but because women were perceived only as objects and not as subjects. Depending on what level it takes place, it can lead to rape, domestic violence or psychological trauma. But exactly because of this, I consider it a sensitive term which requires a lot more thought than the current effortless usage of the word.

Nobody’s Better

A popular opinion claims we should shut up when we talk about women’s objectification because girls do the same thing with men. This has two sides. On one side, whenever men are objectified, people turn a blind eye, with an attitude sounding like “Hey, we’ve been in this position, how do you like it now?” which causes a vicious circle. The other party claims we should regard women’s objectification as unimportant because nobody says anything when it happens to men.

Both arguments suffer from the same problem: regulating a gender’s perception after another. The original problem is limiting a person, no matter the gender, to a product. Blaming the other of being more objectified, wanting one to become just as objectified as its counterpart or normalizing the process because of one’s position place hindrances in combatting the issue. Idiotic terms like ‘honey thighs,’ ‘bagel girl’ or ‘chocolate abs’ are all absurd and offending.

Moreover, an attitude becomes general among reactors to critiques about Koreans: the reference to Westerners. They speak generally about how we shouldn’t compare South Korea with the US or what is usually associated with western values. But whenever something bad about South Korea appears, the same ones jump and say the Western world is much worse. To which I dare to say: so what? I agree more with the first assumption. Both countries, regions and mentalities are intrinsically different, with distinct causes determining their behavior. Why though would the bad wolf, the Western world’s flaws, justify South Korea’s problems? By doing so, we implicitly declare the superiority of the Westerners, much on the lines of ‘It happens to the brighter ones’ and put the other country on an inferior position.

———————————————–

To wrap it up, objectification represents one of the most harmful, yet insidious ways of dehumanizing men and women and converting them into merchandise. I am grateful though this much attention is being paid. So what’s your opinion, Seoulmates? What are your thoughts and bothers on the matter?

(Korea Times, Gender Images, The Korea Herald, Mlodinow, Leonard – Subliminal: How Your Unconscious Mind Rules Your Behavior, onlifezone, High Cut, Newsen, MSN, Nate [1],[2],[3], GQ Korea, tistory, Naver, AOA, thesocietypages, Starship Entertainment)