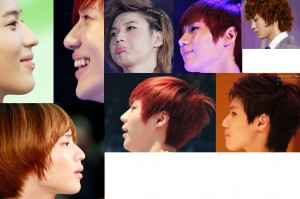

Plastic surgery is not exactly K-pop’s best kept secret. Though only a handful of celebrities have actually admitted to it (ZE:A‘s Kwang-hee, KARA‘s Goo Hara, Super Junior‘s Shindong, to name a few), that idols spend a good portion of their pre-debut years swathed in facial bandages — and make an annual visit or so for a quick nip and tuck — is blatantly obvious. Fans can hardly go a week without reading the latest speculation regarding stars whose faces suddenly appear a bit different than they were before. Weight loss? Exercise? Magic? Well, they’re most likely not going to tell us, so fans often sit in the seat of judgment and guess away. More often than not, they’re likely right.

Plastic surgery is not exactly K-pop’s best kept secret. Though only a handful of celebrities have actually admitted to it (ZE:A‘s Kwang-hee, KARA‘s Goo Hara, Super Junior‘s Shindong, to name a few), that idols spend a good portion of their pre-debut years swathed in facial bandages — and make an annual visit or so for a quick nip and tuck — is blatantly obvious. Fans can hardly go a week without reading the latest speculation regarding stars whose faces suddenly appear a bit different than they were before. Weight loss? Exercise? Magic? Well, they’re most likely not going to tell us, so fans often sit in the seat of judgment and guess away. More often than not, they’re likely right.

But let’s take a moment to think about how a surgically-enhanced celebrity population (and, thanks to idols that do just about everything, a very narrow population at that) affects the viewing public. Interestingly, South Korea’s idol and cosmetic surgery industries seem to have matured side by side; between 2002 and 2010, the number of adults who had admitted to having undergone plastic surgery doubled, while the number of idol groups began to expand in earnest. Today, one in five South Korean women undergo some sort of cosmetic procedure (making South Korea the country that undergoes the most plastic surgery relative to its population in the world) and there are well over one hundred active idol groups in the Korean entertainment industry. Coincidence? Maybe; not a tremendous amount of literature exists to confirm that women (and men) make the decision to go under the knife exclusively due to celebrity influence (people apparently stay mum on the subject), but research increasingly suggests that mass media and bombardment of imagery has a definite effect on how individuals perceive themselves and plastic surgery. Bombardment of imagery… well, that certainly sounds a lot like South Korea’s entertainment industry, now doesn’t it?

However, the cosmetic surgery industry is changing, and here’s the interesting thing: it isn’t just for Koreans any longer. South Korea is now home to a beauty belt that caters not only to its own surgery-hungry populace, but to an increasingly global clientele that is making the journey to South Korea specifically to have plastic surgery done on the peninsula. And this time, it’s all but impossible not to blame the Korean entertainment industry for what we see.

Medical tourism — defined by University of Sydney Professor John Connell as the practice “where patients travel overseas for operations and various invasive therapies” — has become a significant source of revenue for South Korea. In 2011, the medical tourism industry earned a record $116 million, fourteen percent of which was directly attributable to patients from China, Japan, and elsewhere in East Asia specifically seeking plastic surgery. So significant was the revenue earned from medical tourism that it was labeled South Korea’s seventeenth growth engine — and the government anticipates that this figure will only grow, having set a goal of one million foreign patients by 2020.

Medical tourism — defined by University of Sydney Professor John Connell as the practice “where patients travel overseas for operations and various invasive therapies” — has become a significant source of revenue for South Korea. In 2011, the medical tourism industry earned a record $116 million, fourteen percent of which was directly attributable to patients from China, Japan, and elsewhere in East Asia specifically seeking plastic surgery. So significant was the revenue earned from medical tourism that it was labeled South Korea’s seventeenth growth engine — and the government anticipates that this figure will only grow, having set a goal of one million foreign patients by 2020.

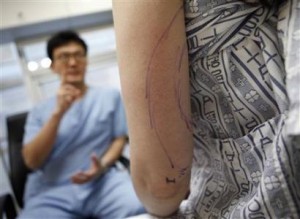

Granted, fourteen percent might not be the largest figure in the world, but nor is plastic surgery the cheapest surgery in the world — and because plastic surgery is not covered by health insurance in South Korea, private hospitals are free to charge as they wish. Additionally, international patients hardly have their pick of any of the 400+ clinics located in the Gangnam region of Seoul (often referred to as the “plastic surgery capital of Asia”); because they likely speak little to no Korean, they will have to make use of one of the larger hospitals in which translation services are offered. Fortunately, the number of hospitals that offer translation — some that can accommodate speakers of over a dozen languages — is on the rise, chiefly because plastic surgeons are starting to realize that the Korean Wave is not just a cash cow for the entertainment industry. Some clinics now offer even Arabic and Mongolian in addition to English, Chinese, Japanese, and Vietnamese.

It’s true that there are many reasons why someone would want to get plastic surgery, and indeed, many reasons why they would choose to do so in South Korea. Asian men and women seeking out double eyelid surgeries or nose jobs, for example, would likely feel more comfortable receiving the operation in Asia, with an Asian doctor who understands the unique structure and shape of Asian features. Buttressing this is the fact that South Korea’s industry stands out in Asia as being highly precise and extremely regulated. While China and Thailand, for example, also have large cosmetic surgery industries, they are plagued by the problem of unlicensed doctors and clinics. China in particular sees hundreds of thousands of malpractice lawsuits related to botched plastic surgery per year. It would make sense that individuals with the necessary capital might want to avoid potential scam and stake their bets in South Korea.

It’s true that there are many reasons why someone would want to get plastic surgery, and indeed, many reasons why they would choose to do so in South Korea. Asian men and women seeking out double eyelid surgeries or nose jobs, for example, would likely feel more comfortable receiving the operation in Asia, with an Asian doctor who understands the unique structure and shape of Asian features. Buttressing this is the fact that South Korea’s industry stands out in Asia as being highly precise and extremely regulated. While China and Thailand, for example, also have large cosmetic surgery industries, they are plagued by the problem of unlicensed doctors and clinics. China in particular sees hundreds of thousands of malpractice lawsuits related to botched plastic surgery per year. It would make sense that individuals with the necessary capital might want to avoid potential scam and stake their bets in South Korea.

However, it is also true that increasing numbers of medical tourists and surgeons alike are citing the Korean Wave as the number one reason for opting to get plastic surgery in South Korea. Surgeon Joo-kwon, who runs the JK Plastic Surgery Center in Seoul, said that he began noticing a heavy influx of Chinese patients in the mid-to-late 2000s, despite having never advertised in China or in Chinese language media outlets.

However, it is also true that increasing numbers of medical tourists and surgeons alike are citing the Korean Wave as the number one reason for opting to get plastic surgery in South Korea. Surgeon Joo-kwon, who runs the JK Plastic Surgery Center in Seoul, said that he began noticing a heavy influx of Chinese patients in the mid-to-late 2000s, despite having never advertised in China or in Chinese language media outlets.

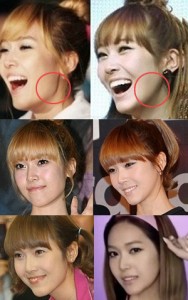

Actually, of all medical tourists to South Korea last year, half were Chinese — and many said that the beautiful faces of Korean actors and pop stars that they watched at home drove them in their quest for beauty. Surgeons report consistently hearing the names of Han Ga-in, Lee Young-ae, and Song Hye-gyo. Chinese college student Christina Wu, who was spotlighted by the BBC in a piece they did covering South Korea’s medical tourism industry last year, told reporters that she wished to look like Kim Tae-hee. Notably, all of the actresses whose names keep cropping up have starred in dramas that enjoyed enormous popularity in China. Indeed, Hallyu-inspired medical tourism is becoming a trend.

In order to meet and encourage demand, the South Korean government is pouring a ton of resources into outreach programs that encourage medical tourism; currently, offices have been established in Singapore, Beijing, and New York to mediate the flow of patients. But even the  South Korean government recognizes the debt that the medical tourism boom owes to Hallyu. Jung Eun-young, deputy director of the health ministry’s policy department, has said that “medical tourism, plastic surgery included, will be a new growth driver for our economy…. and the popularity of our stars is helping us a lot.” And of course, it doesn’t hurt that the very obviously enhanced faces of Korean idols — whose transformations are meticulously documented and available for all to see thanks to the internet — have suggested that with a little snip here and a pinch there, pretty much anyone can turn into a glamorous star.

South Korean government recognizes the debt that the medical tourism boom owes to Hallyu. Jung Eun-young, deputy director of the health ministry’s policy department, has said that “medical tourism, plastic surgery included, will be a new growth driver for our economy…. and the popularity of our stars is helping us a lot.” And of course, it doesn’t hurt that the very obviously enhanced faces of Korean idols — whose transformations are meticulously documented and available for all to see thanks to the internet — have suggested that with a little snip here and a pinch there, pretty much anyone can turn into a glamorous star.

Is medical tourism a good thing? It’s hard to say. On the one hand, it’s bringing incredible amounts of money into South Korea, and in this global economy, pretty much no one is in a position to turn down money. However, it has also had the effect of spreading South Korea’s insatiable surgery fever across Asia — and that may not necessarily be the most positive outcome for everyone involved. While the growth of medical technology is remarkable, some have expressed concern that the Korean Wave is reinforcing the negative self-image of young people and sending the message to international hordes of fans that it is okay to tamper with your body and face if you are unhappy with them.

No one can say whether or not plastic surgery is definitively wrong or right, but as the Korean Wave continues to spread to the farthest reaches of the globe, it is definitely true that more and more people are choosing South Korea as their destination for medical tourism. If nothing else, it will be interesting to see how this trend develops in the future.

(BBC, Malay Mail, Cosmetic Surgery, John Connell, Medical Tourism (Oxford: CAB International, 2010), Reuters, The Economist)