It isn’t often that K-pop makes headlines in major American news publications. For as much proverbial ink is spilled on an uncountable number of fan sites and platforms for social media sharing (Seoulbeats included), K-pop has largely remained outside of the academic realm; as far as I know, there hasn’t been much effort on behalf of the Western media to explain or tie K-pop into larger cultural and societal phenomena in South Korea at large. So you can imagine my surprise when a friend passed along to me an article on South Korea’s mandatory military service and its relation to (surprise!) K-pop that recently appeared in The Atlantic.

It isn’t often that K-pop makes headlines in major American news publications. For as much proverbial ink is spilled on an uncountable number of fan sites and platforms for social media sharing (Seoulbeats included), K-pop has largely remained outside of the academic realm; as far as I know, there hasn’t been much effort on behalf of the Western media to explain or tie K-pop into larger cultural and societal phenomena in South Korea at large. So you can imagine my surprise when a friend passed along to me an article on South Korea’s mandatory military service and its relation to (surprise!) K-pop that recently appeared in The Atlantic.

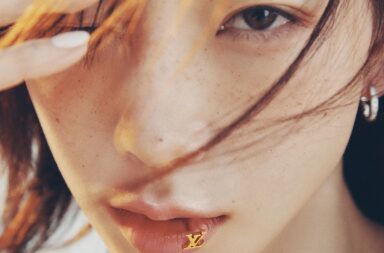

The video that spurred the article was one of a holiday performance that SNSD gave at a military base last month, one that was apparently noteworthy not because of the performance itself, but because of the soldiers’ reaction to SNSD. The original video referred to in the article has been taken down due to copyright claims by MBC, but I found another clip from the same show which is featured above. As you can see for yourself the video featured excessive screaming, floor pounding, jumping up and down, and a few young men who looked like they were about to faint from excitement. In other words, a completely standard response to seeing SNSD in person. I won’t pretend that I didn’t do almost the exact same thing at SM Town Live in New York last October.

video that spurred the article was one of a holiday performance that SNSD gave at a military base last month, one that was apparently noteworthy not because of the performance itself, but because of the soldiers’ reaction to SNSD. The original video referred to in the article has been taken down due to copyright claims by MBC, but I found another clip from the same show which is featured above. As you can see for yourself the video featured excessive screaming, floor pounding, jumping up and down, and a few young men who looked like they were about to faint from excitement. In other words, a completely standard response to seeing SNSD in person. I won’t pretend that I didn’t do almost the exact same thing at SM Town Live in New York last October.

But according to the author of the article, such a feverish, frenzied display of emotion is foreign to the American eye and indicative of a “military culture far different from our own.” He goes on to say:

When I sent the video to Scott Snyder, a Korea expert at the Council on Foreign Relations, he said it was “almost exactly what I was expecting to see.” He encountered one of these “how should we put it, community-based responses” on his first trip to South Korea in 1987, at a university pep rally. “Korea is a more collective-oriented society than the U.S.,” he explained, and that collectivism can be a real asset for young men forced into service and dealing with “the experience of collective loneliness.”

Now, I make no claims to be a Korea expert (and I’m certainly not employed by the Council on Foreign Relations), but this strikes me as a complete and utter cop-out. Chalking up differences between an Asian country and the West to collectivism vs. individualism is tired, oversimplified, and, quite frankly, indicative of lazy scholarship. More to the point, isn’t the American military (I’d even go as far as to say nearly every military) based largely on the idea of putting the collective before the individual?

But my real problem with this piece isn’t that it boils cultural differences between South Korea and the US down to an overused trope — it is that The Atlantic had a real opportunity here to use K-pop in order to delve into some of the issues currently plaguing South Korea’s military culture today, and instead, they opted to essentially throw their hands up and say, “Those crazy Koreans! Never will quite understand ’em, eh?”

What am I talking about?  Well, for one, let’s consider that these soldiers’ over-the-top reactions to seeing nine sexified and scantily clad young women singing, “Oppa, sarang-hae!” are likely not born out of their need to collectively respond to something, but out of their desperate desire to see a woman, ANY woman, while they are stuck living in barracks for two years. This has nothing to do with collectivism or individualism, Korean culture or American culture; the hormonal young man is universal. As the author of the article himself points out, American soldiers serving during the Vietnam War fell into similarly ecstatic frenzies when they were granted the luxury of seeing a pretty woman perform for them — an idea that South Korean cinema expressed in the movie My Lover is Far Away, starring actress Soo-ae as an entertainer for both American and Korean troops in Vietnam. Additionally, does anyone remember Christina Aguilera‘s music video for “Candyman“? The idea of soldiers going crazy at the sight of a woman (or women) is certainly not a new one or one that the modern American cannot comprehend.

Well, for one, let’s consider that these soldiers’ over-the-top reactions to seeing nine sexified and scantily clad young women singing, “Oppa, sarang-hae!” are likely not born out of their need to collectively respond to something, but out of their desperate desire to see a woman, ANY woman, while they are stuck living in barracks for two years. This has nothing to do with collectivism or individualism, Korean culture or American culture; the hormonal young man is universal. As the author of the article himself points out, American soldiers serving during the Vietnam War fell into similarly ecstatic frenzies when they were granted the luxury of seeing a pretty woman perform for them — an idea that South Korean cinema expressed in the movie My Lover is Far Away, starring actress Soo-ae as an entertainer for both American and Korean troops in Vietnam. Additionally, does anyone remember Christina Aguilera‘s music video for “Candyman“? The idea of soldiers going crazy at the sight of a woman (or women) is certainly not a new one or one that the modern American cannot comprehend.

But The Atlantic fails to mention a crucial similarity between US military of the Vietnam War era and the modern day South Korean military , which also indicates a crucial difference between the two today: both are male-dominated forces. Though the US military has evolved and currently has thousands of women serving across the world, the South Korean military relies on the draft and only conscripts men. There are therefore comparatively few women soldiers. Most South Korean soldiers spend the entire duration of their service surrounded by nothing but men on bases that may not be even remotely close to civilization. Add to this the fact that the majority of conscripts are virile young men in the prime of their youth. Now put SNSD in front of them. What on earth do you expect? I would have been more surprised had they not reacted as they did.

Where does K-pop fit into all of this? I’d argue that K-pop is a solid indicator of gender equality not only in Korean society at large, but in the military. Imagine how soldiers might have reacted had it been Super Junior or TVXQ on stage instead of SNSD. With the exception of soldiers whose sexual preference tends towards men, I doubt there would have been as much fist-pumping and ground-pounding. While I can’t be sure, I’d be willing to bet that boy groups rarely, if ever, perform for the troops — and that girl groups do so on many occasions. It might be a stretch, but it seems to me that the fact that the entertaining of troops falls almost entirely to girl groups highlights the fact that South Korea’s military has yet to devise a system that allows for somewhat equitable female participation — which in turn highlights the fact that women do not serve in the military, a point that has often been used as an excuse for South Korea’s abysmal gender equality gap (one of the worst in the OECD). Though strides have been made (Sookmyung Women’s University recently inaugurated an ROTC program), South Korea’s military is nowhere near reaching the level of female participation that the US army currently exhibits. Not that I am terribly in favor of conscripting women into the army alongside men; in fact, I have no policy prescriptions to offer. But how gender equality relates to South Korea’s current system of conscription is certainly something to think about.

Where does K-pop fit into all of this? I’d argue that K-pop is a solid indicator of gender equality not only in Korean society at large, but in the military. Imagine how soldiers might have reacted had it been Super Junior or TVXQ on stage instead of SNSD. With the exception of soldiers whose sexual preference tends towards men, I doubt there would have been as much fist-pumping and ground-pounding. While I can’t be sure, I’d be willing to bet that boy groups rarely, if ever, perform for the troops — and that girl groups do so on many occasions. It might be a stretch, but it seems to me that the fact that the entertaining of troops falls almost entirely to girl groups highlights the fact that South Korea’s military has yet to devise a system that allows for somewhat equitable female participation — which in turn highlights the fact that women do not serve in the military, a point that has often been used as an excuse for South Korea’s abysmal gender equality gap (one of the worst in the OECD). Though strides have been made (Sookmyung Women’s University recently inaugurated an ROTC program), South Korea’s military is nowhere near reaching the level of female participation that the US army currently exhibits. Not that I am terribly in favor of conscripting women into the army alongside men; in fact, I have no policy prescriptions to offer. But how gender equality relates to South Korea’s current system of conscription is certainly something to think about.

Let’s take it a step further: what if SNSD performed for the troops, but the troops were comprised of both men and women? Would we see such an extreme reaction? Would there be the possibility of having male pop groups perform as well? These are difficult and interesting questions upon which to speculate.

The Atlantic had a chance to raise these issues of gender and equality, but in my opinion, they took the easy way out and slapped the whole thing with the blanket label of “cultural difference.” But rather than demonstrate to me the importance of collectivity in Asian societies, the soldiers’ reaction to SNSD proves to me that sometimes, even if the occasion is rare (and I don’t think it is), K-pop provides us with an open door to discuss societal issues of real import. Let us hope that it inspires healthy debate and positive change.