This review contains spoilers, along with mentions of death, suicide, bullying, hazing, sexual harassment, domestic abuse, and verbal abuse. Please read with caution.

“Why isn’t there a single person who would take responsibility?”

This is what the mother of Choi Jun-mok (Oh Min-ae) yells at the officers in charge after Choi Jun-mok (Kim Dong-young) was made to return to the military after having run away. Jun-mok is a soldier who makes a run for it from the army when he can’t take being bullied anymore, but is eventually brought back by the unit of D.P. officers — short for Deserter Pursuit. With there being no protocol in place to hold them accountable, his assailants have a high probability of being let off without consequence. In frustration, she yells, only to receive lacklustre responses of mediocre protocols and insignificant punishments. When the system is built off the concept of anti-responsibility, how can the people within it be anything but?

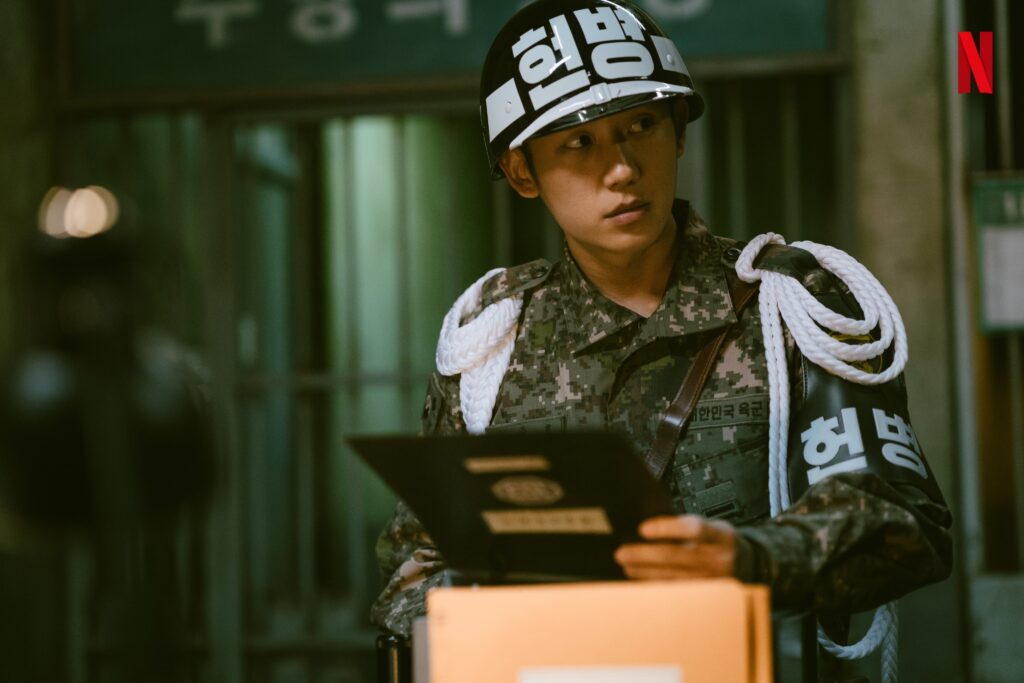

D.P. follows the life of Private An Jun-ho (Jung Hae-in), who is recruited into the D.P. team. As the name suggests, Jun-ho, along with Corporal Han Ho-yeol (Koo Goo-hwan) pursue military deserters under the surveillance of Sergeant Park Beom-gu (Kim Sung-kyun). Through Jun-ho’s perspective, director Han Jun-hee challenges ideas of accountability, morality, corruption, and power in six episodes. More than a drama, however, D.P. comes off as a long-form film split into six smaller acts.

Han Jun-hee mentioned that D.P. has a clutter-free narrative, and that is one of the most accurate ways to explain the drama. With just a handful of episodes, there is no time wasted in introductions and exposition. The first episode goes straight into Jun-ho enlisting, getting recruited into D.P., and accidentally aiding a soldier’s suicide.

Was that jarring to read? The show is just as jarring to watch. Every moment is carefully made uncomfortable, leaving the viewer constantly on edge as the plot unfolds. Even the cinematography follows through with this. Every scene is tinged with a neon quality, more so those that take place within the military base. It is coloured as dark, with a fluorescent blue or yellow tone that lets uneasiness creep into the audience continuously.

More than that, though, the discomfort largely comes from how the plot doesn’t shy away from the concepts of death, violence, and abuse.

Mandatory conscripted service is not an unfamiliar concept, nor is it one that’s unique to South Korea. We hear about the occasional deaths in the news, we tune in to news about wars and the need for military defense, and then we flip the channel and move on to other distractions.

The inner workings of the military are unknown to many of us, especially in countries where its not compulsory for cisgender women to serve. D.P. not only brings these internal issues to the forefront, but it also forces you to confront the worst of those issues, drawing you in with such enthralling storytelling that you don’t even want to flip the channel.

Save for two deserters, every soldier abandons the army because they’ve been bullied. Before Jun-ho is led by senior Ho-yeol to catch these deserters, his first case is under the guidance of Park Sung-woo (Ko Gyung-pyo) — a man only serving because his father holds a political position, a man who has enough money to ‘legitimately’ escape the army, but can’t because of public accountability. That already begs the question: if all soldiers are equal, why can the rich ditch their military duty with no repercussion, whereas the poor are labelled deserters and punished criminally?

Because Sung-woo is protected by both his money and his position in society, his commitment to be a D.P. officer is feeble. He does not care what happens to these deserters. For him, a case is an opportunity to leave camp, party, and stay connected to the real world. This atrocious guidance causes Jun-ho to slip up and eventually give the soldier they’re pursuing a lighter, which he later uses to commit suicide. Sung-woo is transferred to another unit as a result, while Jun-ho is jailed in punishment.

The show makes you question the morality of the D.P. unit. If these men are running away from a system that doesn’t protect them, then do they really have to be brought back? Can you really support what Jun-ho is doing? The thing is, Jun-ho has no choice in what he does, this is his duty. Most of them have little choice, and they are punished when they make a decision that isn’t aligned with the military’s. Moreover, most of these soldiers run away to commit suicide, so the D.P. team does save lives. Jun-ho and Ho-yeol genuinely do it to help soldiers, and the military supports them so that they don’t have a suicide scandal on their hands.

Even when the plot isn’t as heavy, it relentlessly does not let the audience take a break from other social commentary. Seniors in the military bullying younger enlisters, sexually harassing them, hitting them until they bleed, and hazing is consistently highlighted throughout the entire show. In fact, it is these smaller abuses of power that leave the audience reeling more than death, because the finale of D.P. shows how the accumulation of harassing someone can feel like a slow death, but with no end.

Cho Suk-bong (Cho Hyun-chul) and Hwang Jang-soo (Shin Seung-ho) have a victim-bully relationship respectively, and their convoluted relationship is one of the very few that is explored throughout all six episodes. There is a lot to unpack about just this relationship, but one of the most important themes brought across with their relationship is the idea of the real world versus the military. In the military, Jang-soo harassed Suk-bong because he could, because it was fun, and because everyone does it. He was in a position of power because he was senior. Suk-bong then deserts the army and goes on a spree to kill Jang-soo in revenge after the latter completes his service, and Suk-bong’s anger makes him much more powerful than Jang-soo.

There is a clear switch between the abuser and the victim. The army base segregates the soldiers from real life; they live a life that almost doesn’t feel real. This idea is relayed multiple times. When Jun-mok’s mother yells at his superiors, the men automatically hunch and lose their bravado.

Yes, these men have power in the military, but once they’re socialised to the larger world again, they realise that a lot of the power given to them was temporary. And when they can’t align the different dynamics between these two worlds, they struggle. It also helps that every scene filmed in the army is given a faded quality that makes military life feel unreal: it transports both characters and viewers to another world.

As a viewer, I protected myself from thinking too much about how much abuse occurs by telling myself that this is a dramatised Netflix show. Imagine my shock when I found out the show is based off a webcomic that was in return based off real-life events. The disconcerting part is that the screenwriter and webcomic author Kim Bo-tong has toned down the stories compared to what he actually experienced.

Kim Bo-tong focuses a lot on guilt and responsibility, particularly with Jun-ho’s character. Jun-ho’s father hits his mother and the pain on his mother’s face haunts him at night. The face of the soldier who committed suicide gives him nightmares. He feels like he’s failed them all. He can’t save all his comrades from abusers. He doesn’t know how to help his mother. Jun-ho’s background, saviour complex, and his multidimensional character is a huge deciding aspect in how D.P progresses.

He’s a police to soldiers. He brings the bullied back to the places they’re bullied. However, he’s not a fan of it like us. He does it, but reluctantly. He’s constantly picked on at base too. It’s difficult to have extreme like or dislike for him, and the same goes for every character on the show.

Within just six episodes, D.P. constantly makes you question your morals and judgement. What is responsibility? Who should be responsible? Is a bystander absolved of guilt? Can selfishness and selflessness co-exist? Is selfishness bad? There is so much explored in the few hours of D.P. that it feels like each episode deserves its own review.

The stellar cast and official soundtrack do wonders working in tandem with the direction and cinematography of the show. There is a lasting and holistic impact from the show; other than the drama itself, the OST is haunting, melancholic, and emotive. With the way that each song is used, every song brings you back to notable points in the drama and keeps it echoing in your mind.

It also helps that every actor brings forth an unforgettable performance. Of course, this comes at the cost of main characters not being as developed. However, like mentioned, D.P. is very clear in what it wants to convey; although the headlining characters are not fleshed out, what is shown is enough to both empathise with and understand them. An extra kudos to Hae-in and Goo-hwan for knocking their acting out of the park.

D.P. is a show that comprehends and conveys stories of South Korean men that we don’t talk about often. At the same time, it holds them accountable for the mess that the militaristic system is and tells them to face the facts. D.P. comforts and confronts at the same time, and this balance is what makes it appealing. It is easily one of the better, if not best, dramas to come out of the industry this year.

(For viewers: There’s a post-credit scene in the final episode. Don’t miss out on it.)

(Naver[1][2], Tatler Asia, Times of India, YouTube. Images via Netflix Korea.)