The Israeli TV series Prisoners of War (2009-2012), adapted by Showtime as the popular American series Homeland (2011-present), will be finding a new home in Korea.

The Israeli TV series Prisoners of War (2009-2012), adapted by Showtime as the popular American series Homeland (2011-present), will be finding a new home in Korea.

Star J Entertainment recently purchased the rights from Keshet International to adapt the series for Korean broadcast, with Kim Nam-gil as the potential lead. In industrial terms, this means that what is called the “format” of Prisoners of War has been licensed for legal adaptation.

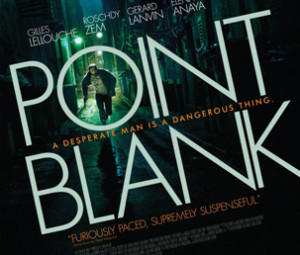

This news is especially timely when considering the significant number of Korean remakes that are due to premiere this year: There’s the Korean remake of popular Taiwanese drama My Queen/Queen of No Marriage, tentatively called Witch’s Love; it’s due for an April premiere, starring Uhm Jung-hwa and Park Seo-joon. Chinese novelist Yu Hua’s Chronicles of a Blood Merchant (1995) will debut as an adaptation on Korean channels later this year, and the Korean remake of French film Point Blank (2010) is set to premiere in May, retitled as The Target.

From last year, the very successful Korean film Cold Eyes is a remake of the Hong Kong film Eye in the Sky (2007). In these cases, we see that Korean companies are taking on not only popular Japanese works (Nodame Cantabile or Cheese in the Trap), which have been deeply discussed in the past in terms of region, but works from countries and parts of the world other than Japan.

It might seem strange that Korean companies invest so heavily in these formats, since remakes are often criticized for being essentially superfluous (“the story has been told already!”) or for not living up to the original work’s glory. There’s a constant consumer demand for newness and innovation, which has impacted the flashy way advertisements, music videos and even newspapers often present their content. The remake appears to stand in stark contrast to these ideals. So in an era that fetishizes the new, why are remakes such a staple of K-entertainment? Why are many Korean production companies investing in stories that have, as some say, “already been told”?

From a purely economic standpoint, remakes and adaptations are cheaper than developing original stories. While production companies must pay for the rights to remake, this is far less costly than the creation of an entirely new concept. With remakes, the skeleton of the story already exists, and a baseline for lighting/sound/costume designers has been set, at least as a point of comparison. Creativity still develops the remake, but there is less time and money invested in the beginning stages.

From a marketing perspective, it’s also a smart move. Remakes can appeal to new regional audiences and feed off existing audiences. Homeland has been broadcast in over 20 different countries, but in East and Southeast Asia, it has only been officially shown in Japan and Vietnam, and the original Prisoners of War in only Israel, Germany, and France according to IMDb. So the Korean version can tap into a different audience market that might never have seen the original, addressing them with fresh material. As an alternate example, Point Blank was actually exhibited in Korea and performed well at the box office, so producers can attempt to predict the national audience for The Target based on the audience for the original. If a foreign film was successful in Korea, it seems reasonable to capitalize on this by adapting it.

From a marketing perspective, it’s also a smart move. Remakes can appeal to new regional audiences and feed off existing audiences. Homeland has been broadcast in over 20 different countries, but in East and Southeast Asia, it has only been officially shown in Japan and Vietnam, and the original Prisoners of War in only Israel, Germany, and France according to IMDb. So the Korean version can tap into a different audience market that might never have seen the original, addressing them with fresh material. As an alternate example, Point Blank was actually exhibited in Korea and performed well at the box office, so producers can attempt to predict the national audience for The Target based on the audience for the original. If a foreign film was successful in Korea, it seems reasonable to capitalize on this by adapting it.

This leads to the idea of risk prediction. Entertainment is an industry bound up in ridiculous amounts of wealth, where the stakes are high and companies will do everything to avoid a single creative flop. In theory, remaking a popular existing story is less risky than developing an original story. Since there will be a positive history behind the presumably successful original, producers can expect the remake to make money as well. There might even be an existing fanbase; for those who enjoyed Queen of No Marriage, Witch’s Love is an opportunity to watch the same kind of narrative unfold again.

Continuing to think about audiences, the ability to localize an unfamiliar or popular story to Korea makes a work more accessible for a Korean audience. Just as Homeland refurbished the central conflict of Prisoners of War in terms of the United States vs. al-Qaeda, the Korean version will reportedly relocate the main conflict to North Korea vs. South Korea. These localized stories become more saturated in some form of Korean culture–and because K-dramas and Korean films definitely have established audiences worldwide and are consumed by more than just Korean nationals, bringing the plot to Korea ends up promoting Korean culture to non-nationals as part of the Hallyu wave.

Remakes have the advantage of hindsight, as well. Creators can observe what worked and what didn’t work for the original and can address strengths or problems accordingly. The chance to improve upon the original demonstrates that remakes are far from barren opportunities for creativity. Though the baseline for the story exists, Korean industrial workers contribute real creative labor to the production, resulting in an ultimately new and inspired media product. This also refutes the idea that remakes represent the takeover of any one culture over another; the adoption of Homeland doesn’t mean that “American culture” will take over “Korean culture” in the show. It represents a hybridity and melding of ideas from different locales. What I like about the remake is that it indicates how great stories are often universal and there is value in the retelling.

However, I don’t want to gloss over some of the very real downsides of remakes. One of the most important drawbacks is that buying a format takes away the opportunity for South Korean professionals, notably writers, to pitch their own original ideas and get their own stories out to the world. In addition, whoever is doing the adaptation cannot keep all of the profits, since they have to initially pay for the rights to remake–though this is still cheaper than developing original ideas, I’m just pointing out how money (that would otherwise have stayed within national boundaries) leaves Korea when international formats are bought and sold. Finally, remakes can also be seen as “playing it safe.” Going with a “tried-and-true” idea that has been done in another context sometimes buys a false sense of security: Risk-taking is part of business, and truthfully, a remake is never a 100% guaranteed success.

I can’t wait to see the Korean adaptation of Homeland, though. Will you be tuning in to any remakes this year?

(IMDb [1, 2, 3], Naver, SCMP, TV Report, Variety [1, 2], Images via Fox 21, Gaumont, WordPress)