With The Devil Judge finale airing last week, one of TV’s smartest and most thrilling dramas has come to an end. It was complex and ambitious in the first half of its run, and it certainly didn’t let up in the second half. Rife with action and allegory, the final episodes took things to the next level as it staged even more riots, killing sprees, and of course, live trials.

Sometimes, the drama’s ambitions led to it toppling over in uneven territory. Character development was strengthened in some ways but stunted in others. Climactic scenes varied from genuinely impressive to distractingly ridiculous. Unable to fully break free from its soapy confines and tired female tropes, the drama buckles. This can be infuriating, especially since it often comes close to perfection.

For the most part, however, The Devil Judge’s grandiosity is grounded by clever and relevant storytelling. It doesn’t shy away from hard-line politics and dares to imagine a country ruled by its worst fears. In this South Korean dystopia, a YouTuber is the head of state, criminals are tried by the court of public opinion, and corruption, racism, and classism all run grossly unchecked. By building on this premise, The Devil Judge’s purpose trumps its form; it’s a drama far greater than the sum of its parts.

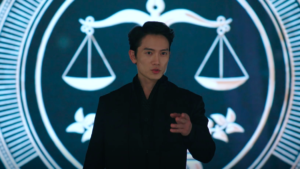

Since we last left the Holmes and Watson duo of Yo-han (Ji Sung) and Ga-on (Jinyoung), their relationship has only become more erratic, oscillating between certainty and uncertainty. Just when it seems like Ga-on has gotten into the anti-hero groove, his conscience pulls him back in doubt. Likewise, when it appears as if Yo-han has been flattened into a respectable but flat protagonist, he snaps back into an unforgiving menace, terrifying in his ability to crush a soul with a single glance.

The Devil Judge has done well to center on the tension between these two. One would think their constant back-and-forths on good and evil would be tiring but, on the contrary, their clashes make for a compelling watch. Whether they’re teaming up or at each other’s throats, their passion always manages to come through. Watching them lob arguments at each other is like watching a game of tennis; it all comes down to speed and form, and even though only one victor emerges, they’ve both put on an incredible show.

Unfortunately, the same cannot be said of other characters, particularly female leads Soo-hyun (Park Gyu-young) and Sun-ah (Kim Min-jung). In an earlier review, it was hoped that Soo-hyun, being the badass that she is, would show more agency outside of Ga-on in the following episodes. This did not happen. Instead, the writers doubled down on love being her sole defining trait. Flashbacks reveal she has always babied Ga-on, even when she was a baby herself, and as she bleeds to death, her very last words are directed to him and his pain only. “Oh, you’re hurt,” she tells him, “I love you.” It’s supposed to be a moving scene, and Jinyoung and Gyu-young certainly deliver it with tender might, but it’s hard to feel for someone so empty.

More a symbol of hope than an actual, lived-in character, Soo-hyun was clearly set up to die; her lack of purpose and backstory make it that much clear. But there is something unsettling about how the female leads get the short end of the stick here. The promising Sun-ah also devolves in later episodes, her spicy duality proving to be nothing more than unevenness. She acts like a murderous girlboss one second and a sympathetic ally in the next, and as such, her character makes less and less sense as the show progresses. She’s touted as Yo-han’s female equivalent, the only person who matches his polarity (the Irene Adler to Yo-han’s Sherlock), but for whatever reason, she’s not given the same careful treatment and redeeming depth.

Oddly enough, the series corrects these errors through its other female characters, namely Cha Kyung-hee (Jang Young-nam) and Oh Jin-joo (Kim Jae-kyung). Kyung-hee, for all her wickedness, has moments of self-awareness and vulnerability that elevate her from caricature to complexity, making her a more effective villain than Sun-ah. “I’m only guilty of trying my best to survive,” she admits in her final moment.

Jin-joo, on the other hand, is a great example of how a female character can succeed without any male attribution. Left out by her teammates Yo-han and Ga-on, she rises from the ranks all on her own. She’s one of the few female characters who doesn’t meet a tragic end, and it’s nice to see her at the finish line with a clearer sense of who she is, sans romance.

Inconsistencies like this also creep up in the drama’s finer details, which can lead to questions like: amidst a nationwide government shutdown, how is Yo-han still able to stream in the DIKE app? Who exactly is in charge of the Ministry of Justice? And where is the military in all of this? Whenever they do show up, they’re either too late or too hidden.

In epic scenes, this manifests in the wonky execution of grand concepts. Riots feel too staged to be taken seriously, and elaborate heists too minimal to be impressive. The idea is there—match the plot’s largeness with ambitious action—but the drama seems constrained by the proverbial boob tube. One can’t help but wonder if The Devil Judge would be more effective either as a movie or as a series backed by the big-budget likes of OCN or Netflix.

Still, it’s best not to get lost in these details. They can be distracting in the moment, but they understandably give way to the larger picture. The drama’s cinematic vision is achieved not through these ambitious sequences, but rather through the more scaled-down but highly clever live trials.

Indeed, the courtroom is where the drama is at its best. The trials don’t just poke at sore spots like harassment or corruption; they dig right into them, forcing all the blood and pus out in a disgusting but satisfying burst. If in the first half, castrations and floggings seemed like unthinkable punishments, episode 14 takes things to the deep end with the electric chair.

Here, in a brilliant UNO-reverse card move, Yo-han uses a loyalist’s staunch patriotism against him by sentencing him to the death penalty, a cause the president has been lobbying for so long. He “attacks the enemy with the enemy’s sword,” as Sun-ah puts it, and the result is a terrifying scene that has Yo-han calmly stare into the defendant’s bloodied, electrocuted body.

In later episodes, we also learn an interesting truth about the powers-that-be. The megalomaniac Heo Joong-se (Baek Hyun-jin) may lead the Blue House, and in effect the country, but he is nothing but a mere puppet, put into power by Sun-ah and two of the country’s biggest conglomerate giants.

It’s bad enough that a former YouTuber has become president, but now it’s also revealed that capitalism is the true ruler of the state. The goal, they claim, is to turn South Korea into “the first country that follows a business model,” hence all the killings. To these bigwigs, people are just items going through the production line, and those who don’t pass quality control are simply thrown into the bin. Literal bodies—of foreign, disabled, and homeless citizens—are sold to other countries for profit. In this regard, The Devil Judge is less a fantasy and more of a bleak but pointed cautionary tale.

Long after the hype has died down, the drama will be remembered not necessarily for its dystopian revolutions or macabre trials (or for the inconsistencies mentioned, for that matter), but rather for its relevance and perceptiveness. Its real strength lies in its ability to take what we know and contort it into something strange and uncomfortable, to transform the screen into a mirror and make us question our beliefs.

The season finale, aptly titled “The Devil Judge?”, leaves viewers with a question rather than a neat conclusion. Was Yo-han the devil all along? He may have played dirty, but in the end, he has achieved what many hopeful lawmakers and game-changers have failed to do: topple the establishment and turn the so-called capitalist pyramid on its head. Does this make him the villain, or the hero the country needed to finally incite meaningful change?