Momoland have carved out a niche for themselves in the referential, quirky digital space. Their breakout hit “Bboom Bboom” introduced the members through mock infomercials, showcasing them as products for sale. The follow-up, “Baam!” made the most of social media dance trends with a mash-up of TikTok-able choreography. Both MVs, combined with their dances were a recipe for viral success while JooE gained singular popularity with her jovial dancing. So, when a collaboration opportunity arose to cover one of TikTok’s most viral tracks, Momoland were shoe-ins for the role.

Like many a TikTok song, Chromance and Mark Layton‘s “Wrap Me in Plastic” flew under the radar in 2017 when it was released, but saw a spike in popularity when the platform re-discovered the track in 2020. A new MV, conceived mid-year, re-worked the concept as an animated girl who depends on TikTok viewers’ opinions to such an extent that she misses out on her real-life relationship with her boyfriend. In this new conception, the “master” and “mine” relationship pertains to social media audiences and influencers, questioning who is really leading whom.

Fans and TikTok users were excited when Chromance announced a collab with Momoland for a Korean version of the hit. The trouble is the way the lyrics and concept are communicated to a real-world context, involving the use of living women. MLD Entertainment sheds the subversion of the original and instead presents a troubling narrative.

In the “Wrap Me in Plastic” MV, the Momoland members transform into a group of internet influencers, living in what seems to be a Hype House set up, creating digital content for their viewers. Content houses have conceptually been around for a while. From Silicon Valley “hack houses“, 1600 Vine, the now-defunct Clout House, to the newest TikTok content farms — communal living/working spaces that require constant productivity to stay relevant are widespread. In the case of this MV, the members inhabit a doll house of their Master’s design.

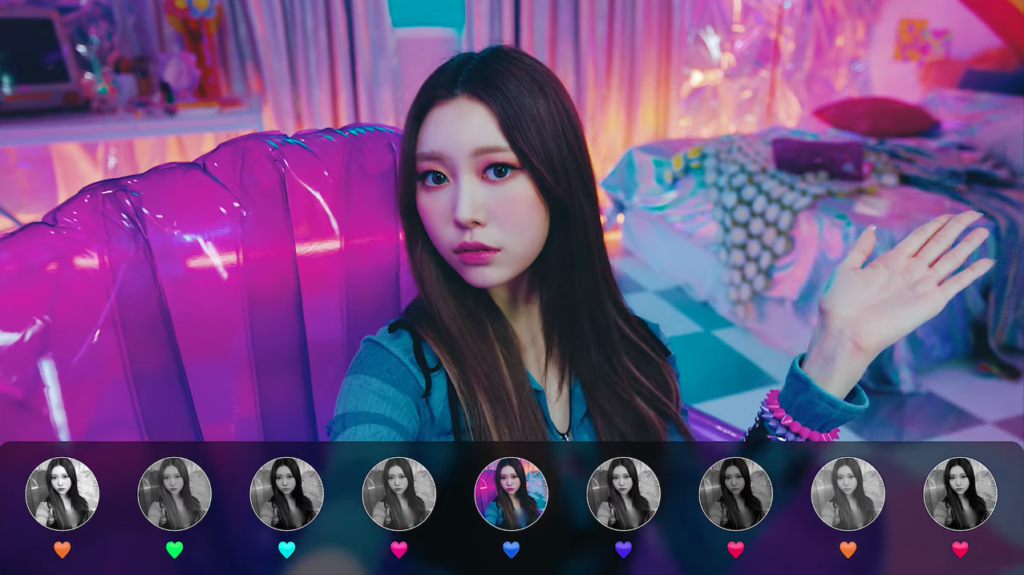

The members’ style is, of course, informed by trends, complete with cowboy hats and soft e-girl vibes. They smile in front of ring lights, and brood seductively with broadcasted versions of themselves on retro television screens. In the virtual world, the members exist as gifs and TikToks of them doing viral dances — primarily those of Chromance, who also appears in video pop-ups looking in on the members and instructing them on the right moves. In the “real” world, they are hardly different: doll-like fantasies lounging around their home, slaves to the audience they exist for.

Towards the end of the MV, the members all gathered and perfectly in costume, Chromance makes a surprise visit. The members peep through a door to see a man in a silver mask. Instead of suspecting what looks like a character from The Purge, he is welcomed into the home and a dance party ensues. This kind of storyline isn’t uncommon. Twice’s warm welcome of JYP dressed as Wee Willy Winky, in “TT” springs to mind. Unfortunately, letting a masked stranger into a shared work/living space isn’t the main problem with this MV.

It’s not exactly fair to take issue with MLD for the lyrics of “Wrap Me in Plastic.” This is a cover and there is no shame in expressing kinky desires in music. However, it is more than fair to take issue with how these lyrics are paired with the images onscreen and the message they send. Unlike the previous iterations of the MV, this version abandons all sense of critique of the parasocial relationship and instead embraces and romanticizes it. Innuendo is plentiful, and the provocative edge to the lyrics becomes uncomfortable when we see exactly how MLD imagines this M/s fantasy.

Wrap me in plastic and make me shine

We can make a dollhouse, follow your design

Let’s build a dog out of sticks and twine

I can call you master, you can call me mine

K-pop is no stranger to incorporating fetish aesthetics and themes. From fanfiction to fashion, kink and fandom overlap frequently. Momoland’s “Wrap Me in Plastic” though, uses fetish undertones in a way that begs the question: who exactly is this for? Fetish objects and themes are introduced with a faux-naiveté, which seems intended to allow the sexual connotations to splash across the screen without comment. It is almost impossible to miss — a swollen hotdog borders the screen while the girls sing about calling someone “Master” for goodness’ sake — but the audience is expected to feign ignorance.

It’s my first night out with you

Treat me right and buy me shoes

Let me be your fantasy, Play with me

I wanna be your girl

The way you can tell that MLD knows what they’re doing without actually knowing what they’re doing is that the “Wrap Me in Plastic” MV is a smorgasbord of kinks. Do you want M/s? Bondage? You’ve got it. A little DD/LG? ASFR? The members do that, too. They become dolls of every fantasy, just like the lyrics say. You can show up at their home, and they’ll welcome you with open arms, looking exactly the way you’ve seen them on your screen this whole time. The members are entirely accessible, willing, and ultimately objects without agency. They become indistinguishable from their online avatars.

There is an attempt to soften this subtext. MLD includes shots of the members surrounded by phones, live streaming their confinement. They also had one (1) shot of Nancy having a fan blown on her that attempted to break the fourth wall. Even the reality element of the story strips the performers of their impetus. They are trapped in a voyeuristic bubble of plushies and inflatables. Waiting for their members to join them while frenetically snapping selfies still places them in a role that lives to maintain the fantasy. By failing to subvert — or reinterpret the lyrics — MLD present the Momoland members as objects, defined by the male gaze, whose only purpose is to fulfill the audience’s fantasies in both the digital and physical worlds.

The choice to use influencers and the e-girl phenomenon as the dominant aesthetic is one that fits in with a particular stereotype. The e-girl trope draws from 2000’s nostalgia, anime, internet culture, and yes, fetish and has long been associated with sex and sex work. Consumers of this content [predominately male] have lusted over and slut-shamed participants in the scene. This has been capitalized on to earn income and provoke attention, in some cases. Instagram star Belle Delphine sold “Gamer Girl bathwater” for 30$ a bottle and whipped followers into a frenzy after opening an account on Pornhub, only to post a video of her eating a photo of PewDiePie. Doja Cat trolled her fans by promising to “show you guys my boobs really hard” if her song “Say So” topped the Billboard Hot 100 Singles’ chart. Her song was a huge success but she declared the promise a prank and moved on. Both these examples generated backlash and harassment for the women but showed they understand their audience. Internet horniness can be harnessed for a time but it’s not without danger.

You may think this article makes too much of an otherwise cute MV. Bubblegum kink shouldn’t be shamed, nor should it be forcibly excluded from pop culture. These are valid arguments, but when the intention is to sneak fetish play into MVs geared towards young fans who will reproduce the contents of this viral video on TikTok, it is concerning. Another side of the fanbase: heterosexual male viewers may watch this content and feel a parasocial connection, possession even, of the influencers (or in this case, artists) they follow. As far as this MV is concerned, boundaries don’t exist. The women onscreen are eager, willing dolls begging to be played with in an environment completely controlled by the “Master”.

The comeback takes on a sinister cast when recalling the photo manipulation endured by Nancy. Faked photographs, appearing to be spycam footage of her undressing, were circulated online. MLD released a statement communicating its intention to take legal action against the perpetrators. This censure is discordant with the message in the song, released shortly after the scandal was discovered. It feels perverse, that a few weeks after being manipulated into a sexual context against her will, Nancy will perform a song telling fans to use her however they like.

This transgression of the boundaries of the virtual world and the real world plays into misconceptions about kink and BDSM. Safe, sober, and consensual are not just buzzwords. The responsible exploration of kink can’t be separated from boundaries.

An uncritical acceptance of a dominating force can result in trauma, both emotional and physical. The increasingly bizarre Armie Hammer saga, fraught with explicit details of his fantasies and ideas about BDSM reveals how kink can be used to harm people: a man preying on women online, imposes his fantasies on them, enters into BDSM play without proper negotiation, and misinterprets “dominance” as a free pass to inflict bodily harm without consent. There are very real consequences for the trivialization of kink into a virtual consumption in which the fantasy overrides the consent of the participants.

Critiquing this MV doesn’t come from a desire to kink shame anyone. The video’s narrative trivializes and fetishizes the kind of parasocial digital relationship that has led to real people getting hurt. The virtual space of fantasy and the real world of human bodies are two separate things, and MLD pretending that they aren’t is incredibly harmful. There are a handful of K-pop MVs that have dealt with kink in a responsible way. Sadly, this isn’t one of them.

This article is a collaboration between editors Chelsea and Janine.

Our team works hard to share critical perspectives of K-pop daily, all on a voluntary basis. Donate via Ko-fi (ko-fi.com/seoulbeats) or join our Patreon (patreon.com/seoulbeats) to keep us going!

(YouTube, Vox, Kotaku, The Gamer, Complex, [2], Dazed Digital, CR Fashion Book, Genius, Buzzfeed, Dexerto, Bitch Media. Images via MLD Entertainment.)