It’s comforting to think that there is an afterlife, that a divine and infallibly just system awaits us in another world. Just as reassuring, too, is the notion that evil exists outside of us, not within, and whenever we’re in danger of getting too close to it, there are saviors—angels, heroes, or in this case counters—who will try their best to keep it at bay. These are some of the building blocks of most religions, after all, and the possibility of there being life after death, the very hope of it, is what keeps a lot of us from spiraling into a nihilistic, useless mess.

Maybe that’s why people have latched on to the surprise hit that is The Uncanny Counter, an afterlife-based demon-fighting drama that raked in a whopping 11% viewership rating on its January 24 finale. On its second-to-the-last week of airing, the show also came in first in popularity and internet buzz, according to a report from the Good Data Corporation, beating out tVN’s romantic comedy True Beauty. As OCN’s most successful feature in years and Netflix’s top Korean drama in regions like Hong Kong and Taiwan, it’s not surprising that a second season is already in the works.

We noted that early on its run, when it had less of this fanfare, The Uncanny Counter showed a lot of promise. It dared to take on different genres (superhero, crime, and fantasy to name a few!) and answer big, philosophical questions about good (is there such a thing?) and evil (is it inevitable?). It also seemed to experiment on anti-heroes and sympathetic villains, a brave but risky move to be sure.

However, as audiences steadily grew—almost every new episode held a record rating, defeating the one that came before it—this daringness noticeably declined. The show started to lean heavily on its predictable crime bent despite ripe opportunities for something more multifaceted, and any hope of it tackling the moral nuance it teased in early episodes vanished as it increasingly became more feel-good than fearless.

It would appear that by trying to pander to its growing fanbase, The Uncanny Counter compromised the complexity that made it such an interesting story in the first place, and the resulting cracks manifested in poor characterization and world building. Of course, it still had its charms—namely the amazing chemistry between its four leads and the genuinely enthralling action they get down to—but it sadly didn’t live up to its full, critical potential.

This first became clear when the show’s most complex character thus far, the evil spirit Ji Cheong-shin (Lee Hong-nae), was reduced to an archetypal bad guy. He had all the makings of a great villain, but as the story progressed, his tragic backstory played second fiddle to his one-dimensional bloodthirstiness. The sympathetic persona introduced in the show’s first half resurfaced only at the last minute—when he was about to die, it was revealed he had a soft spot for kids—but by then it was too late. It was tough to feel for the guy whose killings up until that point had been so pointless and merciless. The revelation was supposed to add gravitas to his death, but it only elicited more confusion than sympathy.

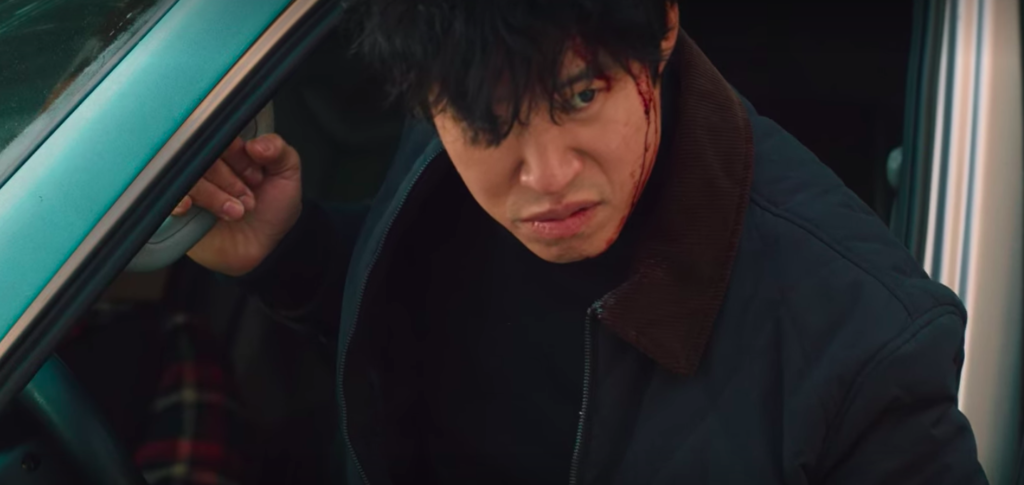

Poor characterization also plagued the show’s leads, including and especially “ace” counter So-mun (Jo Byung-gyu). So-mun is the indisputable protagonist of the show, and alongside all the crime solving and fighting, this is supposed to be his story of growth. But whenever he is faced with tense situations that force him to change, he’s bafflingly given the easy way out. When he was suspended from his counter duties due to rage issues, the punishment was immediately lifted when it became clear only he could save his group from evil. When, in the finale, he was given a choice to save his dead parents’ souls from vanishing or his very much alive grandparents from a crash—a representation of his own conflict between being stuck in the past and alive in the present—he is saved from having to make a decision as his fellow counters swoop in and save the day.

Not only do these convenient cop-outs hide his internal struggle, they also rob him of a chance to reflect on his flaws and consider the possibility that he might not actually be as perfect as he seems. It’s as if the show doesn’t trust its audience enough to know that they can still follow his journey despite a few misses, that they can distinguish a flawed man from an evil one, and that they can still choose to support him. It’s a disappointing turn of events for a show that started with such morally complex ideas, and one can’t help but wonder if the show’s commercial success had anything to do with this sudden simplification of affairs (or with the main writer’s abrupt exit due to “differing opinions,” for that matter).

For better or worse, the show also decided to ease up on the details of the Yung afterworld. Little is said about what the rules are and how they actually work there. It’s so ambiguous that when they decided to introduce an overseeing committee to oversee the overseers, people just went with it, because sure, why not. Anything can happen in an unexplained world. In a similarly confusing vein, when the counters are in battle, their counterpart guardians in Yung are always terrified because they could die as well—when So-mun was dismissed it was because his recklessness endangered the life of his guardian Wigen (Moon Sook). But aren’t the guardians already dead? Where exactly do the double-dead go? The last time Wigen’s host died, she found the nearest body she could enter, which happened to be So-mun’s. So why are they so scared?

It’s possible this vagueness is an allegorical message about the nothingness of real death, as opposed to TV death, where once you’re gone, you’re gone, and not even the wisest among us knows what happens next. But it’s more plausible that the showrunners decided to skip this part of world building in order to focus on the crime plot happening on Earth, which is actually quite rich and intricate, the absence and irrelevance of Yung notwithstanding. It smartly involved almost every character and spanned from political to corporate to environmental in its scope. The show honed in on the crime genre with much finesse and gusto. It’s just shame that there wasn’t enough to go around to make it the multi-genre feat it could have been.

Apart from its impressive crime dealings, the show has other merits to it as well. What it lacked in character, it made up for in chemistry. The strong rapport between its four leads So-mun, Mo-tak (Yu Jun-sang), Ha-na (Sejeong), and, Mae-ok (Yum Hye-ran) is magnificently intact whether they’re manning their cover-up noodle bar or battling it out with goons and stray demons. Equally commendable is the dynamic action they consistently engage in. Whether it’s Ha-na’s flying kick or So-mun’s new power of the week, it’s to their credit that the action never falls flat throughout the 16-episode run.

For a show that is largely about death and destruction, The Uncanny Counter is oddly charming and light on its feet. More than just being an offshoot of the cast’s great chemistry and combat skills, though, this seems to be a deliberate move towards the simple and widely likeable, as evidenced by the show’s diminished characterization and world building. Despite being important elements themselves, it’s likely they were seen as excess baggage, reduced to hasten the show’s quick rise to the top.

In fact, how The Uncanny Counter handles grief is pretty telling of this motive. Anytime a loved one dies on the show, the character either exacts revenge on the offender or communicates with the deceased through a medium. Until full closure is attained, no one rests easy. Of course, in real life, closure is not so instantly achievable. Grief is drawn out, and moving on is almost never assured. Moreover, good and evil are never as black and white as the heroes and villains in this show—they’re gray and muddled and frustratingly complex.

Yet in the great style of commercial hits, The Uncanny Counter shows us what we want to see, not what we need to see, and when it comes to death, we want to see that like the simple, smiling souls on the show, we’ll be alright. This is primetime, cable TV after all, not an indie film festival. OCN needs to show its paying viewers something upbeat, uplifting, and escapist even; something serious but not too challenging, smart but not too complex—all the better to engage its viewers, but never alienate them. As crowd-pleasers go, it will remain as mediocre as possible, or until viewers start to get bored.

For that, the show’s presumable solution is adding more of the same thing it has now. In the finale, it was hinted that season 2 will be about recruiting more counters, and instead of just Jungjin City, they’ll be looking over all of South Korea. It’s certainly an exciting premise, but it might not be enough to fortify the show’s weakening narrative core, which is in dire need of depth, not scope—that is, if the show still plans on succeeding critically as well as it does commercially.

(Naver [1][2][3], SCMP, TheKoreaTimes. Images via Netflix and OCN.)