There is one K-pop comeback in 2020 that is uncontested in its popularity and influence, whose beaming energy and chic style has managed to find its way in almost every major act this year. I’m referring, of course, to none other than the star of soul itself — disco!

From the groovy rhythm of Exo-SC’s “1 Billion Views” to the eclectic displays of GFriend’s “MAGO,” and even to the suave choreographies of chart-toppers like J.Y. Park and Sunmi’s “When We Disco” and BTS’ “Dynamite,” the genre’s roaring return in the K-pop scene is unmistakable. But while the whys and hows of the phenomenon seem to be well-covered— critics suggest that the trend is influenced partly by Western fads and partly by a need to escape from the pandemic’s stifling restrictions — what exactly is disco beyond the four-on-the-floor beat, the multi-color pleats, and the blaring synths? Was the period, as the latest music videos seem to suggest, marked by nothing more than dance parties and quick getaways?

To fully appreciate disco’s comeback, it’s vital to know that K-pop actually references the beloved era in ways other than just look and sound. Through the stories it tells, it also alludes to a critical but often forgotten part of the genre: its history.

As disco continues to dominate the stage, now might be a good time to go beyond popular references and dive deep into its origins. Armed with this knowledge, not only will we be able to find a deeper understanding of the songs and videos that borrow from it, but we’ll also be able to give credit where credit has been long overdue.

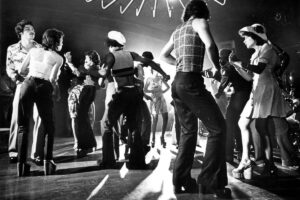

Despite its more glamorous depictions, disco in the late 1960s to early 1970s was subversive and edgy. Beyond the neon glow and sparkly glitter, right behind the flimsy walls of the first discotheques, there danced, simultaneously hidden and uninhibited, the sound’s true progenitors: runaways shunned elsewhere for their sexuality or skin color.

Members of the African, Latino, and queer communities didn’t just revel in but indeed created a whole subculture that celebrated diversity and sensuality at a time when they were unwelcome and even criminalized. The early disco sound sprung from African-American genres like jazz, soul, and R&B, while its prominent, rousing vocals were largely adopted from gospel music. This was accompanied by distinct Latin percussions, beats, and a dance style that recalled Salsa’s intimate steps.

DJs, some of the very first in fact, repeatedly played songs like Eddie Kendricks’ “Girl You Need a Change of Mind,” The Love Unlimited Orchestra’s “Love’s Theme,” and Manu Dibango’s “Soul Makossa” to wild success. They also organized underground dance parties that welcomed people of the same sex to drink and dance together without any threat of being harassed by the police. Music journalist Vince Aletti likened going to The Loft, one of the very first disco clubs, to “going to a party, completely mixed, racially and sexually, where there wasn’t any sense of someone being more important than anyone else.”

Disco’s popularity was boosted even further by the wide release and even wider acceptance of the 1977 film Saturday Night Fever, which, gritty and hard-hitting as it was, decided to shine the spotlight on its straight, white lead (John Travolta). This unwittingly ushered in a new era of disco, one that churned out cheesy copies for profit and one that was overwhelmingly white. Despite disco’s rich history before this, Travolta and The Bee Gees, who provided the film’s soundtrack, suddenly became the face of disco. “The Bee Gees put a white face on what was basically black and Latin music,” author John-Manuel Andriote explained in an interview with historian Hadley Meares, “and it exploded in popularity.”

As it does now, disco offered people solace when they found none. “The problems that we shared during the day, we came together in the evening to overcome together or to get away together,” disco legend Gloria Gaynor once said. “And one of the ways we came together was on the disco dance floor.” All this social and musical openness made disco a huge hit. Almost overnight, discotheques went from being fringe to mainstream. According to Aletti, by 1975, around 2,000 disco clubs popped up in the US alone, while its inimitable sound spread beyond the country’s borders, making its way to Europe and even Asia (in South Korea this inspired the rise of local disco-funk pioneers Lee Eun-ha, Kim Nam-mi, and Yoon Sin-nae).

When disco was said to have died in 1979 (at a violent mob in Chicago aptly known as the “Disco Demolition”), the public had little thought for what it was— a precious platform for the disenfranchised — and remembered only the final and sanitized echoes of what it used to be. Though its distinctly funky sound continued to live on in the music that followed (house, EDM, hip-hop), it wasn’t until the 2000s that it was welcomed back in its fully groovy form.

Now that disco is making another big return at the dawn of a new decade — in the sprawling and exciting field of K-pop no less — we can honor the music’s buried but crucial history by scrutinizing how it’s being applied in recent iterations. Not only will this kind of analysis properly acknowledge disco’s roots, but it will also illuminate the ways in which disco, as a sound and subculture, is being interpreted by the K-pop industry today.

A good example of this is “MAGO,” which fully embraces what the genre is all about. In the music video, the girls of GFriend shed off their modest office wear and head to the dancefloor to introduce their new, bold selves. With its seductive undertones and constant references to breaking free, “MAGO” continues disco’s legacy of newfound liberty and sexual freedom, popularized by the likes of Gloria Gaynor, Donna Summer, and Labelle, all of whom shattered social norms when they brazenly sang about female sexuality and empowerment. In the same way the “MAGO” era saw unprecedented participation by the members in songwriting and production, Labelle used disco’s openness to strengthen their control over their own sound. As Nona Hendryx recalls, “This was really a group of women who were making their own decisions about the music they wanted to write and perform.”

By contrast, the release sang in “Dynamite,” which sees BTS dance around in smart suits and slicked ‘dos, doesn’t seem to be based on any real motive other than to just look good and have fun. While the track does share the vibrancy and escapism inherent in disco, offering a cheerier alternative to the reality we’re currently stuck in, any resemblance to the genre stops there. On closer look, it lacks the actual “funk and soul” it sings of, opting instead for a simple sound and safe message that makes it more classic pop than anything else. Here, disco exists as a mere aesthetic, recalled in neat pleats, colorful backdrops, catchy hooks… and not much else. Like the trendiest of styles, it is worn for flair, not purpose.

This is not to say that all of the genre’s new songs should be serious or transgressive, but when something as popular as “Dynamite” forgoes disco qualities like freedom and spunk in favor of empty elation, it risks propagating the version of disco we’re already all too familiar with, one that is synthetic, gimmicky, and far removed from its rich past.

Compared to the aforementioned tracks, “When We Disco” isn’t as absolute in its take on liberation. In the music video, Sunmi and J.Y. Park are forbidden lovers, constantly whisked away from each other only to find true solace in disco. Though it cheekily alludes to the era of risky romance, it’s also insistently safe as it spotlights a heterosexual couple instead of a queer one. If authenticity were a spectrum, “When We Disco” may be found somewhere in the middle, prodded by intention but hampered by execution.

There are plenty more examples from this year alone—Brave Girls’ “We Ride,” Yukika’s “Soul Lady,” Seventeen’s “Home Run,” to name a few — all of which are open to further scrutiny. They may be a valiant interpretation of disco like “MAGO” or a loud but hollow echo of it like “Dynamite.” However, it’s likely they’ll be closer to “When We Disco,” a piece of work that vacillates between the two, because K-pop is anything but black and white. The sheer volume of its acts will provide some variance, further blurring the line between mere trend and actual homage. One can only hope there will be more room for the “MAGO”s of the industry, works that prove disco can continue to be a significant genre for expressing liberation in the same way the marginalized groups who established it intended it to be.

After all, as the critics note, disco reemerged in 2020 as a musical beacon of hope. Its playfulness and vividness are a welcome escape from a more dismal reality, and the latest releases have done their job of sprinkling the K-pop scene with the brightness both the artists and fans needed.

It’s great that disco still gets to bring comfort to those who need it more than 50 years after it was founded, but wouldn’t be better if it gets to be remembered for its history as well? As much as disco is about escape, it’s also about liberation, and the sooner we incorporate this truth in our K-pop viewings, the better. As a classic disco tune suggests, turn the beat around. Let’s retrace disco’s past and remember its glorious origins because we’ll love to hear it, love to hear it perhaps even more than we do now.

(BBC, Aeon, Vibe, Blk Girl Culture, Juno Reviews, Vignesh R. Nalliah, The Hankyoreh, Telegraph, AMA Journal of Ethics. YouTube [1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10]. Images via Big Hit Labels, JYP Entertainment, ESTIMATE Entertainment, Brave Entertainment, San Francisco Chronicle/Barton Silverman, The Guardian/Rex Features)